Announcing the Galaxy Zoo JWST project!

We are thrilled to announce the launch of the Galaxy Zoo JWST project, with ~300,000 galaxy images from the COSMOS-Web survey taken with NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)! We now need your help identifying the shapes of these galaxies by classifying them on Galaxy Zoo. These classifications will help scientists answer questions about how the shapes of galaxies have changed over time, and what caused these changes and why.

As we look at more distant objects in the Universe, we see them as they were billions of years ago because light takes time to travel to us. With JWST able to spot galaxies at greater distances than ever before, we’re seeing what galaxies looked like early in the Universe for the first time. The shape of the galaxies we see then tells us about what a galaxy has been through in its lifetime: how it was born, how and when it has formed stars, and how it has interacted with its neighbours. By looking at how galaxy shapes change with distance away from us, we can work out which processes were more common at different times in the Universe’s history.

Image credit: COSMOS-Web / Kartaltepe / Casey / Franco / Larson / RIT / UT Austin / CANDIDE.

Now, with data from JWST, we’re able to look deeper into the cosmos and further back in cosmic time than ever before, investigating the wild and wonderful ancestors of the Milky Way and the galaxies which surround us in today’s Universe. Thanks to the light collecting power of JWST, there are now over 300,000 images of galaxies on the Galaxy Zoo website that need your help to classify their shapes. If you’re quick, you may even be the first person to see the distant galaxies you’re asked to classify. You will be asked several questions, such as ‘Is the galaxy round?’, or ‘Are there signs of spiral arms?’. These classifications are not only useful for the scientific questions we want to answer now, but also as a training set for Artificial Intelligence (AI) algorithms. Without being taught what to look for by humans, AI algorithms struggle to classify galaxies. But together, humans and AI can accurately classify limitless numbers of galaxies.

We here at Galaxy Zoo have developed our own AI algorithm called ZooBot (see this previous blog post for more detail), which will sift through the JWST images first and label the ‘easier ones’ where there are many examples that already exist in previous images from the Hubble Space Telescope. When ZooBot is not confident on the classification of a galaxy, perhaps due to complex or faint structures, it will show it to users on Galaxy Zoo to get their human classifications, which will then help ZooBot to learn more.

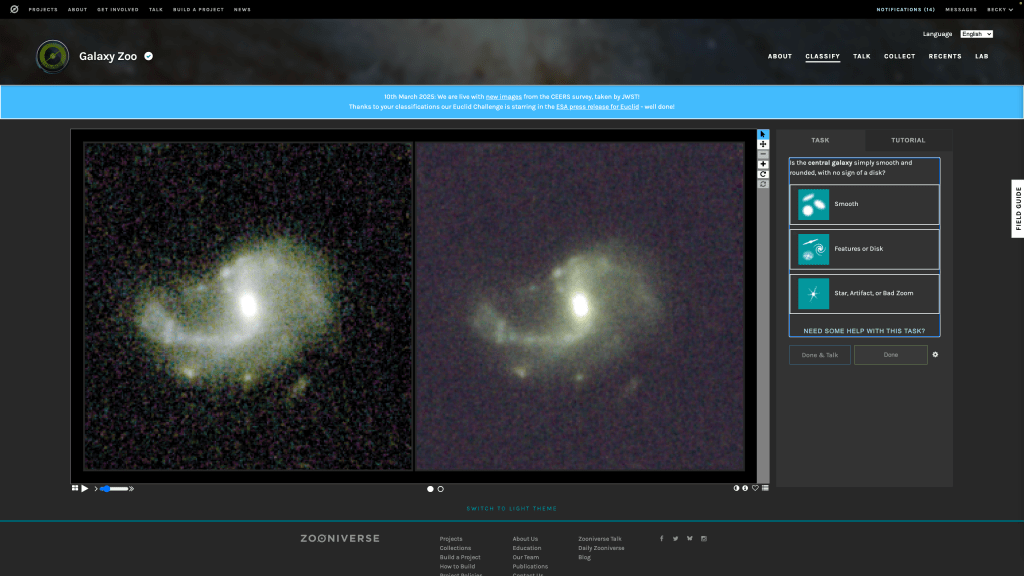

You might also notice a slight difference to the classification interface for this project. Each image has two main colour versions available to help you see different features in the galaxy. Both of these colours images are built from the four COSMOSweb filters (F115W, F150W, F277W, and F444W) but with two different scalings. On the right the scaling is set to reveal bright central features more clearly, while the lefthand version should reveal fainter outskirts. You can also see the original four single filter images if you’d like in the flip book (see the two circles below the centre of the two images). By providing all of these images we’re hoping that it’ll be easier for volunteers to classify the images, and allow us to extract the most information about a galaxy from each image.

We’re really excited about this project on the team, not least because it’s been in the pipeline for a long time! We have had two team meetings at the International Space Science Institute (ISSI) in Bern, Switzerland over the past year in preparation for this launch, so it’s great to be finally at this point. We’re particularly excited though because of the science that will be made possible thanks to this project. Given JWST’s incredible sensitivity to light (thanks to that beautifully large mirror!), we’ll be able to classify the shapes of galaxies out to much greater distances than ever before. This means we can see further back in time in the Universe’s history to trace how the shapes of galaxies have changed earlier in cosmic time. We’ve already taken a look at your classifications from the pilot JWST project we ran on ~9000 galaxy images from the CEERS survey (another JWST galaxies survey, that’s smaller then COSMOS-Web that’s launching today) and with your help we found disk galaxies and galaxies with bars out to greater distances than ever before. So with even more JWST galaxies now on the site, all of us on the team are buzzing with excitement thinking of all the new discoveries coming our way soon.

If you do decide to take part: THANK YOU! We appreciate every single click. Join us and classify now.

Announcing the Galaxy Zoo: Euclid project!

We are thrilled to announce the launch of the Galaxy Zoo: Euclid project, with 820,000 galaxy images fresh from ESA’s Euclid Space Telescope’s first year of operations! This will be the public’s first chance to see survey images from the Euclid telescope. If you take part in the project, you could be the first human to ever see that image from Euclid. Not only that, you could be the first human in the Universe to ever lay eyes on the galaxy in the image. These classifications will help the Galaxy Zoo and Euclid science teams answer questions about how the shapes of galaxies have changed over time, and which processes in the Universe have caused these changes.

First off, if you’re not familiar, let’s start with the Euclid Space Telescope. The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Euclid space telescope launched in July 2023 and has begun to take its survey of the sky. Euclid has been designed to look at a much larger region of sky than the Hubble Space Telescope or the James Webb Space Telescope, meaning it can capture a wide range of different objects all in the same image – from faint to bright, from distant to nearby, from the most massive of galaxy clusters, to the smallest nearby stars. With Euclid, we will get both a very detailed and very wide view (more than one third of the sky) all at once.

In November 2023 and May 2024, the world got its first glimpse at the quality of Euclid’s images with Euclid’s Early Release Observations which targeted various astronomical objects, from nearby nebulae, to distant clusters of galaxies. Below is an incredible image of the 1000 galaxies in the nearby Perseus cluster taken by Euclid. What you’ll notice in the background though is a plethora of distant galaxies all ready for their shapes to be classified! At the latest count, there’s 100,000 background galaxies in this one image alone.

The sheer volume of data from Euclid is a huge challenge to us astronomers; Euclid is set to send back 100GB of data per day for six years. That’s a lot of data, and labelling that through human effort alone is incredibly difficult. So we will once again be deploying our AI algorithm, called Zoobot, for this project. If you want to know more about Zoobot, Mike wrote a great blog post explaining it in more detail last year. In short, Zoobot learns from Galaxy Zoo volunteers to predict what they would say for new galaxy images. After being trained on the human answers that you will contribute in the next few months, Zoobot will then be able to give us detailed classifications for hundreds of millions of galaxies found by Euclid over its next six years of observations, creating the largest detailed galaxy catalogue to date and enabling groundbreaking scientific analysis on topics like supermassive black holes, merging galaxies, and more.

Zoobot will sift through the Euclid images first to classify the “easier” galaxies that we already have a lot of examples of from previous telescopes. However, for the galaxies where Zoobot is not confident in its classification, perhaps because the galaxy is unusual, it will send those images to volunteers on Galaxy Zoo to get their human classifications, which then help Zoobot to learn more. The Galaxy Zoo: Euclid project will therefore see AI and humans working together to learn more about our Universe.

We’re really excited about this project on the team, not least because it’s been in the pipeline for a long time! But also, because of the science that will be made possible thanks to this project. Given Euclid’s unique design that gives us both a very detailed and very wide view, we’ll be able to classify the shapes of galaxies out to much greater distances than ever before. This means we can see further back in time in the Universe’s history to trace how the shapes of galaxies have changed earlier in cosmic time. While JWST also makes this possible, the images from JWST are from a much smaller area of sky. Euclid, however, will cover one third of the entire sky and give us a look at the entire galaxy population that’s visible to us from within the Milky Way. Even as I’m typing this I’m getting excited at the population statistics that GZ: Euclid will make possible!

What’s more is that Euclid’s main focus has always been to understand the distribution and effects of dark matter in our Universe. Dark matter is matter that we know is there because of its gravitational effect on things around it, but it doesn’t emit, reflect, or absorb light, so we can’t see it. The Euclid team are planning to make a 3D map of the positions of all the galaxies they find, and trace out where all the visible and dark matter is. Combining this map with your classifications of the shapes of galaxies, we will for the first time be able to ask the question: how does dark matter affect the shapes of galaxies over cosmic time?

So I hope I’ve convinced you about how exciting this project is and you are now ready and raring to go with your classifications. You can find a link to the project below. If you do decide to take part: THANK YOU! We appreciate every single click. Join us and classify now.

Becky Smethurst, on behalf of the the Galaxy Zoo and Euclid science teams

P.S. Some of you might notice that metadata is absent for these images for now. This is because the images you’re seeing are not yet publicly available. Extra data will be added upon Euclid’s first data release in 2025.

#GZoo10 Day 3

We’re ready for the final day of the Galaxy Zoo 10 workshop at St Catherine’s College in Oxford; it’s been great to have so many people following along on the Livestream – yesterday’s talks are still up, and today’s schedule is:

09:30 Alice Sheppard (Forum Moderator 2007-2012)

10:00 Brooke Simmons (UCSD)

10:20 Nic Bonne (Portsmouth)

10:40 Coffee

11:00 Coleman Krawczyk (Portsmouth)

11:20 Mike Walmsley (Edinburgh)

11:40 Carie Cardamone (Wheelock)

12:00 Karen Masters: Summary (Portsmouth)

We’ll be blogging these talks as they happen here but you can also keep an eye on the twitter hashtag for updates too!

Our first speaker this morning is Alice Sheppard who was here from the beginning as a forum moderator on the original Galaxy Zoo site. She’s talking about the past 10 years and how she got involved with Galaxy Zoo site. She was very keen to get involved in the project and help classify galaxy images. After finding images that weren’t easily classifiable, users started to email members of the science team to ask them what to do. After this happened many times, the team realised that a place where users could talk together and interact with the team about classifications would be really useful. So the Galaxy Zoo forum was born! Alice was one of the first people to sign up and was asked to moderate the forum – she (along with other moderators) even started welcoming each new user who signed up with a friendly “Welcome to the Zoo!”

.@PenguinGalaxy: how the volunteers are welcomed to the Galaxy Zoo forum #GZoo10 pic.twitter.com/xxIviVO70e

— galaxyzoo (@galaxyzoo) July 12, 2017

Alice is now talking us through some of the findings made by the users. These discoveries including the Green Peas, which when first spotted by the users they immediately started investigating what they were using the links to the science survey site. In the original Galaxy Zoo there was also no button for an irregular galaxy, so users started collating their own collection of irregular galaxies! But what makes users keep coming back to the Galaxy Zoo forum time and time again? One success story was the Object of the Day – the moderators even crowd sourced the users to find good images!

.@PenguinGalaxy: Some of the volunteers started recognizing shapes in Galaxy Zoo #GZoo10 pic.twitter.com/eIlxpA0OxZ

— galaxyzoo (@galaxyzoo) July 12, 2017

Alice has discussed some suggestions for future engagement with users online – always give people room to chat; whether it’s about astronomy or not at all! Remember: as good as you think you citizen science system, tools, tutorials etc are – the volunteers will teach you how to do it better!

.@PenguinGalaxy's research questions #GZoo10 pic.twitter.com/BYQk8ju5Yw

— galaxyzoo (@galaxyzoo) July 12, 2017

Next up this morning is Brooke Simmons talking about what she’s calling probative outliers. The things that tend to break the mould and challenge our world (or Universe!) view. She starts with the bulgeless galaxies – those that look like pure disks – but are hosting growing super massive black holes in their centers. This is weird because the most accepted theory is that super massive black holes grow in mergers of galaxies BUT mergers also grow bulges – so how did these bulgeless things grow their black holes? Brooke is showing us some beautiful follow up observations of Galaxy Zoo SDSS images taken with the Hubble Space Telescope that will help to try and figure this out.

This galaxy hosts a luminous supermassive black hole. Hubble reveals rich substructure, including star-forming knots along the spiral arms. pic.twitter.com/SKufkF7IbV

— Brooke Simmons (@vrooje) May 22, 2017

Thing is, Brooke only has about 100 of these galaxies – but not for lack of trying! They just seem to be really rare. If we could actually cover the southern sky in the same way that SDSS covered the northern sky, Brooke would be very grateful! Could we also use trained machines to pick out the weird outliers as well? In which case, Brooke thinks we need to adapt the next iteration of Galaxy Zoo to be both machine as well as user friendly. This will mean leaving things behind but let’s not be afraid to make changes!

.@vrooje: let's actually let the machines do some of the work #GZoo10 pic.twitter.com/d8MIVp4Xgr

— galaxyzoo (@galaxyzoo) July 12, 2017

Next up, we have Nic Bonne from Portsmouth who’s going to tell us all about making luminosity functions using the data from Galaxy Zoo. So what’s a luminosity function? It’s basically a count of the number of galaxies at different luminosities (or brightness) which can give us clues about how the Universe formed and evolved.

Next is @coffee_samurai and Raffles, the awesome guide dog, on the luminosity function of GZ galaxies #GZoo10 pic.twitter.com/dvlrGATk5t

— galaxyzoo (@galaxyzoo) July 12, 2017

Luminosity functions are especially interesting if you start making them for different morphologies or colours of galaxies. This is what Nic has been doing using the Galaxy Zoo 2 classifications. He’s found something a bit weird though – that the galaxies classified as smooth seem to be more numerous than those classified as featured at the low luminosity (low mass) end. Bringing the colour of the galaxies into this picture as well shows you how similar red featured and red smooth luminosity functions are. Nic says there’s a lot more to do be done with this work though, including using Ross’s new debiased classifications to improve the sample completeness and investigating how the luminosity functions change shape for different kinematic morphologies.

@coffee_samurai's results on the luminosity functions: smooth galaxies are more numerous than featured ones at low masses #GZoo10 pic.twitter.com/mbqIyvageI

— galaxyzoo (@galaxyzoo) July 12, 2017

Next up is Coleman Krawczyk who’ll be showing us some of the initial results from the Galaxy Zoo 3D project. This project asked users to draw around the features of a galaxy on an image so that researchers could pick out the spectrum of that particular feature using MaNGA data. Users were asked to either mark the centre of the galaxy or draw around any bars or spiral arm features.

#gzoo10 some potential @galaxyzoo tasks are harder than others …. pic.twitter.com/hMd3qpAKHx

— Alice Sheppard (@PenguinGalaxy) July 12, 2017

Users could also choose which classification task they would prefer to help out with. This meant that the easy classification task of marking the centre of the galaxy was finished within a couple of days – whereas the spiral drawing task took 6 weeks for classifications to finish. Coleman has now reduced these classifications and has made “maps” for every galaxy marking which pixels are in which features. He’s now started making diagnostic plots to map the star formation rate in the different features of classified galaxies. Turns out we’re going to need more classifications in order to do the science we want to, so this project could have new data coming soon!

Next up is Mike Walmsley, who’ll be joining the research team as a PhD student in October.

Next is Mike Walmsley who will be joining the Galaxy Zoo team in 3 months' time #GZoo10 pic.twitter.com/agN3fmuOQH

— galaxyzoo (@galaxyzoo) July 12, 2017

He’s not yet done any work with Galaxy Zoo but as part of his Masters research he looked at doing automatic classification of tidal features in galaxies. His goal was to write a code that trained a machine, using a neural network, to detect these tidal features. He also figured out that masking the main galaxy light in the image makes it easier for the machine to spot tidal features. So does this method actually work? It identifies tidal features with ~80% accuracy – which is actually a much higher quality than other automated methods! He’s hoping to apply these methods to new and bigger surveys during his PhD.

Next up is Carie Cardamone from Wheelock College talking about her work building on the the discovery of the Green Peas by Galaxy Zoo volunteers.

AND IT'S THE PEAS 💚💚💚💚 #gzoo10 pic.twitter.com/TcWkBucD6H

— Alice Sheppard (@PenguinGalaxy) July 12, 2017

So what are the Green Peas? First up their name describes them pretty well because they’re small, round and green. Carie originally wanted to study them because she thought they might be growing super massive black holes, but it turned out instead they have extremely high star formation rate for their relatively small mass. There has been many further studies on these objects so we now know a lot more about them, but one thing we still don’t really know is what galaxy environment they live in. Carie is trying to quantify this but the first problem was that she didn’t have enough Peas! There’s only 80 in the original GZ2 sample but now with the better analysis tools Carie has been able to select 479 candidate Peas. Analysing this sample and comparing it to a sample of well studied luminous red galaxies, the results suggest that peas are less clustered. i.e. the Peas have fewer galaxy neighbours.

#GZoo10 Peas aren't quite so round in Hubble pic.twitter.com/t544m8I6KA

— Alice Sheppard (@PenguinGalaxy) July 12, 2017

We’re now coming towards the end of the meeting (sad times guys) and to remind us all why we’re here and what we talked about, Karen Masters is going to give us a summary of the past couple of days. She’s first pointing out how great we are as a team and the impact the research has had on the galaxy evolution community. Fitting for the 10 year anniversary is that we have 10 published papers with over 100 citations!

Finally. @KarenLMasters giving a summary of the #GZoo10 pic.twitter.com/l6ZzewUQaI

— galaxyzoo (@galaxyzoo) July 12, 2017

Karen has noticed a couple of themes from the past few days that she’s summarised for us. The first is that we have to keep engaging with the Galaxy Zoo community on Talk. The second is that we shouldn’t be afraid of change – let’s not get hung up on how it’s always been done and think about how best to do it now. The third is that galaxy’s are messy and we need to think carefully how we use the classifications. The fourth is that the users will always give you what you ask for – so be careful what you ask! But sometimes you get more than you asked for and end up with a wonderfully collaborative research team!

.@KarenLMasters: Happy 10th Birthday Galaxy Zoo! #GZoo10 pic.twitter.com/AqWrBWNMPW

— galaxyzoo (@galaxyzoo) July 12, 2017

New paper on active black holes affecting star formation rates!

Good news everyone, another Galaxy Zoo paper was published today! This work was led by yours truly (Hi!) and looks at the impact that the central active black holes (active galactic nuclei; AGN) can have on the shape and star formation of their galaxy. It’s available here on astro-ph: http://arxiv.org/abs/1609.00023 and will soon be published in MNRAS.

Turns out, despite the fact that these supermassive black holes are TINY in comparison to their galaxy (300 light years across as opposed to 100,000 light years!) we see that within a population of these AGN galaxies the star formation rates have been recently and rapidly decreased. In a control sample of galaxies that don’t currently have an AGN in their centre, we don’t see the same thing happening. This phenomenon has been seen before in individual galaxies and predicted by simulations but this is the first time its been statistically shown to be happening within a large population. It’s tempting to say then that it’s the AGN that is directly causing this drop in the star formation rate (maybe because the energy thrown out by the active black hole blasts out or heats the gas needed to fuel star formation) but with the data we have we can’t say for definite if the AGN are the cause. It could be that this drop in star formation is being caused by another means entirely, which also coincidentally turns on an AGN in a galaxy.

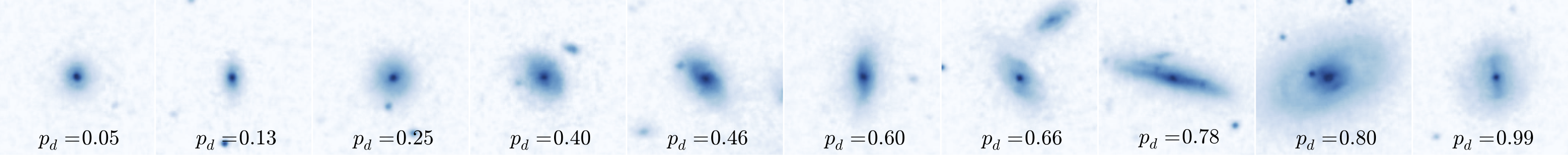

A random sample of galaxies which host a central active black hole used in this work. The disc vote fraction classification from Galaxy Zoo 2 is shown for each image. Images from SDSS.

These galaxies were also all classified by our wonderful volunteers in Galaxy Zoo 2 which meant that we could also look whether this drop in the star formation rate was dependent on the morphology of the galaxy; turns out not so much! If the drop in the star formation rate is being caused directly by the AGN (and remember we still can’t say for sure!) then the central black hole of a galaxy doesn’t care what shape galaxy it’s in. An AGN will affect all galaxies, regardless of morphology, just the same.

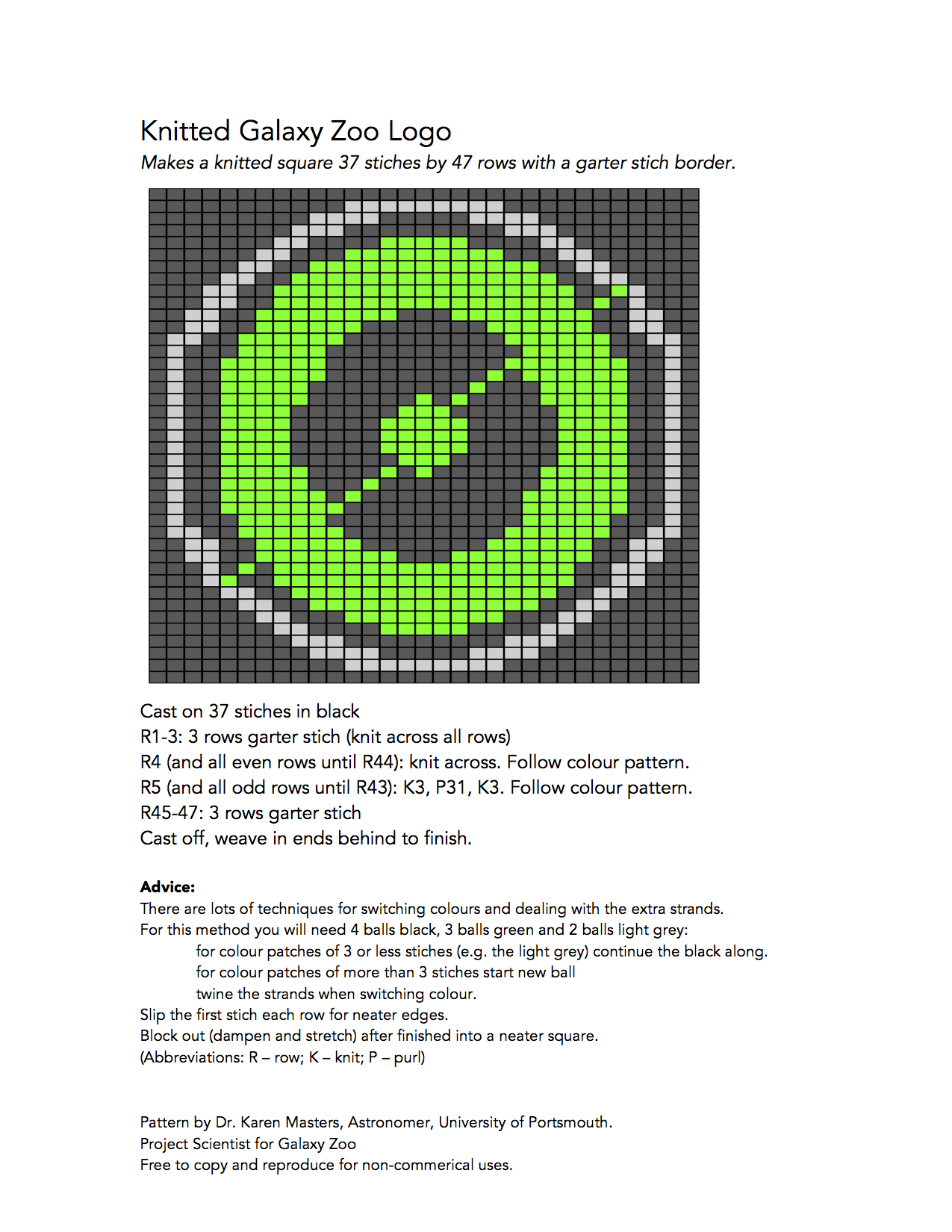

A perfect woollen gift for the SEVENTH anniversary

In the UK on a seventh anniversary the traditional gift is one made of wool. So considering it’s the SEVENTH anniversary of Galaxy Zoo TODAY (July 11th) our very own, super talented Karen Masters has knitted us the Galaxy Zoo logo!

If you feel like getting your astronomical knit on for this momentous occasion, here’s a few inspirational photo’s.

Karen also knitted our favourite Penguin Galaxy as a birthday present for the lovely Alice :

And check out the skills of Jen Greaves and the NAM Knitters who knitted a WHOLE GALAXY CLUSTER at this year’s National Astronomy Meeting in Portsmouth:

For those of you itching to stretch your creative muscles but haven’t been struck by that bolt of inspiration yet, here’s a KNITTING PATTERN (a first I believe for the Galaxy Zoo blog) for the Galaxy Zoo logo to keep you busy…

Our SEVEN Favourites

To honour the SEVENTH anniversary of Galaxy Zoo (July 11th) we’ve put together a gallery of the Science Team’s favourite images from the site (and why) for your visual pleasure…

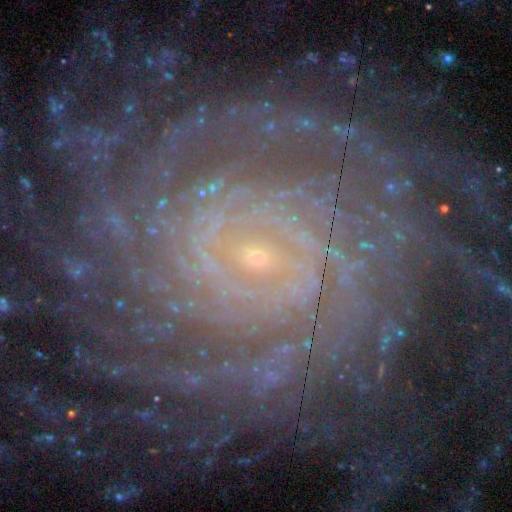

Chris’s favourite: I love the flocculent spiral galaxies. The ones you can stare at and still have no idea how many spiral arms they have.

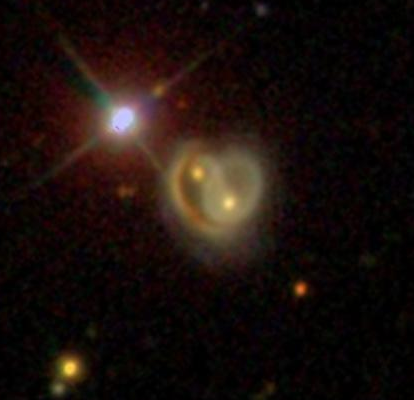

Karen’s favourite: I’m a sucker for merging galaxies, despite the fact that I work on barred galaxies mainly! This one which looks like the yin-yang symbol (or maybe a heart) is a particular favourite. It’s amazing that the Universe can be so vast that we can find galaxies in so many different shapes.

Kevin’s favourite: The penguin galaxy shows the power of human pattern recognition – and a crucial stage in galaxy evolution!

Brooke’s favourite: when the latest Galaxy Zoo launched, the volunteers made a find almost right away that turned out to be a very rare kind of object called a gravitational lens. I love this image because it shows not just the variety of things that are out there in the Universe — in this case the very distant universe — but also the rare place that Galaxy Zoo itself occupies. It’s a diverse community and diverse images like this are part of the reason why.

Kyle’s favourite: did you know that we can spell Galaxy Zoo out of galaxies? The users originally started collecting a list of galaxies that look like letters and now we have writing.galaxyzoo.org thanks to Steven. Since it’s the anniversary, here’s my favourite letter G.

Bill’s favourite: Hanny’s Voørwerp really started something – the blue stuff in the image – other teams are now finding similar objects at smaller and larger distances too.

Becky’s favourite: this amazing image has SO much going on in it – mergers, interactions, spirals, bars, ellipticals, grand designs, foreground stars etc. It feels like a visual representation of thoughts in my head at times, which is clearly why I love it.

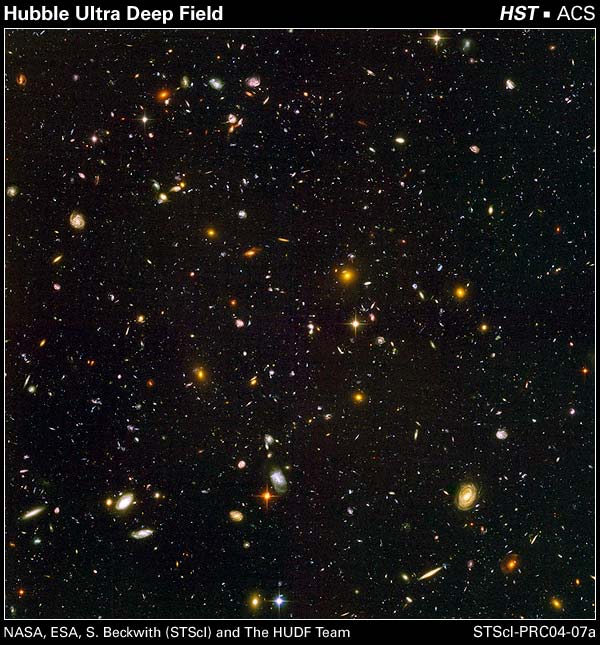

BONUS:

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field!!!! Just to remind us all why we’re all here. Every single thing you can see in this image is a galaxy – even the most minuscule of dots. And the size of the image on the sky is about 1/20 the size of the Full Moon… Let’s just all take a minute to let that sink in as we stare and wonder...

The SEVEN wonders of Galaxy Zoo

Friday 11th July 2014 is the SEVENTH anniversary of Galaxy Zoo! So to celebrate this momentous achievement, we’ve put together a list of seven of the greatest Galaxy Zoo discoveries (so far!); all thanks to YOU, the classifiers…

1. Chirality of Spiral Galaxies

One of the first major results from Galaxy Zoo wasn’t even Astronomical. It was Psychological. One of the questions in the original Galaxy Zoo asked whether spiral galaxy arms rotated clockwise or anti-clockwise; we wanted to check whether they were evenly distributed or whether there was some intrinsic property of the Universe that caused galaxies to rotate one way or the other. When the Science team came to analyse the results they found an excess of anti-clockwise spinning spiral galaxies. But when the team double checked this bias by asking people to classify the same image that had been flipped there was still an excess of anti-clockwise classifications; so it’s not an astronomical phenomenon. Turns out that the human brain has real difficultly discerning between something rotating clockwise or anti clockwise; check out this video if you don’t believe me – you can watch the dancer rotate both ways! Once we’d measured this effect we could adjust for it, and we went on to establish that spirals which were near each other tending to rotate in the same direction.

2. Blue Ellipticals

The enigmatic blue ellipticals in many ways started the Galaxy Zoo. Galaxies largely divide into two: spiral galaxies like our Milky Way shining with the blue light of young stars being constantly born, and the “rugby ball-shaped” elliptical galaxies who no longer make new stars and thus glow in the warm, red light of old stars. Clearly, when galaxies stop making new stars, they also change their shape from spiral to elliptical. But how exactly does this happen? And what happens first? Do galaxies stop forming stars, and then change their shape, or the other way round? Answering that question is the first step in understanding the physics of transforming galaxies. With the Galaxy Zoo, we found a whole population of blue ellipticals: galaxies which have changed their shape, but still have young stars in them. With their help, we’ve been making a lot of progress in galaxy evolution. It looks like a galaxy merger, a giant cosmic collision, changes the shape of galaxies from spiral to elliptical and then somehow – and very rapidly! – star formation stops. We don’t know quite why yet, but we think active black holes are involved. This is hugely relevant for us as in a few short billion years, the Milky Way will crash into our neighbour, the spiral Andromeda galaxy. And for a short time, the Milky Way and Andromeda will be a blue elliptical before star formation in the newly-formed Milky-Dromeda ceases. For ever.

A normal red elliptical and normal blue spiral on the top row. Unusual discoveries of blue ellipticals and red spirals on the bottom row.

3. Red Spirals

Ellipticals are red, Spirals are blue, Or so at least we thought, until Galaxy Zoo…. Think of your typical spiral galaxy and you’ll probably picture it looking rather blueish. Thats’s what astronomers used to think as well – suggest a red spiral to Edwin Hubble and he probably would’ve told you not to be so ridiculous. Before Galaxy Zoo if astronomers saw something looking red they generally tended to think it was elliptical; however to the untrained eye, the colour does not bias any classifications, which means that you all found lots of red spirals and discs which were hiding in plain sight. This put the cat amongst the pigeons for our galaxy evolution theories because, as said earlier, we thought that when galaxies stop making new stars, they also change their shape from spiral to elliptical. The red spirals mean that we now have a different evolutionary path for a spiral galaxy where it can stop making new stars and yet not change its shape. We now think that those spiral galaxies which are isolated in space and don’t interact with any neighbours are the ones that make it to the red spiral stage.

4. Green Peas

The Green Peas, discovered by Citizen Scientists due to their peculiar bright green colour and small size, are a local window into processes at work in the early Universe. Although, they were in the data for many years, it took humans looking at them to recognise them as a class of objects worth investigating. First noticed in some of the earliest posts of the Galaxy Zoo Forum in 2007, a group of dedicated citizen scientists organised a focused hunt for these objects finding hundreds of them by the summer of 2008, when the Galaxy Zoo science team began a closer look at the sample. The Peas are very compact galaxies, without much mass, who turn out new stars at incredible rates (up to several times more than our entire Milky Way Galaxy!). These extreme episodes of star formation are more common to galaxies in the early Universe, which can only be directly observed very far away at high redshifts. In contrast to the distant galaxies, the Peas provide accessible laboratories that can be observed in much greater detail, allowing for new studies of star formation processes. Since their initial discovery, the Peas have been studied at many wavelengths, including Radio, Infrared, Optical, UV and X-ray observations and detailed spectroscopic studies of their stellar content. These galaxies provide a unique probe of a short and extreme phase of evolution that is fundamental to our understanding of the formation of the galaxies that exist today.

5. The Voørwerp

Probably the most famous new discovery of Galaxy Zoo has been Hanny’s Voørwerp. Hanny van Arkel called attention to it within the first few weeks of the Galaxy Zoo forum with the innocent question ”What’s the blue stuff?”, pointing to the SDSS image of the spiral galaxy IC 2497. The Sloan data alone could indicate a gas cloud in our own Galaxy, a distant star-forming region, or even a young galaxy in the early Universe seen 10 billion light-years away. After a chase to obtain new data, above all measurements of the cloud’s spectrum, with telescopes worldwide, an unexpected answer emerged – this galaxy-sized cloud was something unprecedented – an ionization echo. The core of the galaxy hosted a brilliant quasar recently on cosmic scales, one which essentially turned off right before our view of it (so we see the gas, up to 100,000 light-years away from it, shining due to ultraviolet light form the quasar before it faded). This had never before been observed, and provides a new way to study the history of mass surrounding giant black holes. Further observations involved the Hubble Space Telescope and Chandra X-ray Observatory (among others), filling in this historic view. The cloud itself is part of an enormous stream of hydrogen, stretching nearly 300,000 light-years, probably the remnant of a merging collision with another galaxy. As it began to fade, the quasar started to blow out streams of energetic particles, triggering formation of stars in one region and blowing a gaseous bubble within the galaxy. In keeping with the nature of Galaxy Zoo, the science team deliberately had much of this unveiling play out in full view, with blog entries detailing how ideas were being confronted with new data and finding themselves supported, discarded, or revised. The name Hanny’s Voørwerp (which has now entered the astronomical lexicon) originated when an English-speaking Zoo participant looked up “object” in a Dutch dictionary and used the result “Voørwerp” in a message back to Hanny van Arkel. Following this discovery, many Zoo volunteers participated in a focused search for more (the “Voørwerpjes”, a diminutive form of the word) – as a result we now know 20 such clouds, eight of which indicate fading nuclei. Other teams have found similar objects at smaller and larger distances; Hanny’s Voørwerp really started something!

Probably the most famous new discovery of Galaxy Zoo has been Hanny’s Voørwerp. Hanny van Arkel called attention to it within the first few weeks of the Galaxy Zoo forum with the innocent question ”What’s the blue stuff?”, pointing to the SDSS image of the spiral galaxy IC 2497. The Sloan data alone could indicate a gas cloud in our own Galaxy, a distant star-forming region, or even a young galaxy in the early Universe seen 10 billion light-years away. After a chase to obtain new data, above all measurements of the cloud’s spectrum, with telescopes worldwide, an unexpected answer emerged – this galaxy-sized cloud was something unprecedented – an ionization echo. The core of the galaxy hosted a brilliant quasar recently on cosmic scales, one which essentially turned off right before our view of it (so we see the gas, up to 100,000 light-years away from it, shining due to ultraviolet light form the quasar before it faded). This had never before been observed, and provides a new way to study the history of mass surrounding giant black holes. Further observations involved the Hubble Space Telescope and Chandra X-ray Observatory (among others), filling in this historic view. The cloud itself is part of an enormous stream of hydrogen, stretching nearly 300,000 light-years, probably the remnant of a merging collision with another galaxy. As it began to fade, the quasar started to blow out streams of energetic particles, triggering formation of stars in one region and blowing a gaseous bubble within the galaxy. In keeping with the nature of Galaxy Zoo, the science team deliberately had much of this unveiling play out in full view, with blog entries detailing how ideas were being confronted with new data and finding themselves supported, discarded, or revised. The name Hanny’s Voørwerp (which has now entered the astronomical lexicon) originated when an English-speaking Zoo participant looked up “object” in a Dutch dictionary and used the result “Voørwerp” in a message back to Hanny van Arkel. Following this discovery, many Zoo volunteers participated in a focused search for more (the “Voørwerpjes”, a diminutive form of the word) – as a result we now know 20 such clouds, eight of which indicate fading nuclei. Other teams have found similar objects at smaller and larger distances; Hanny’s Voørwerp really started something!

6. Bars make galaxies redder

A galactic bar is a straight feature across a spiral galaxy. It’s the orbital motions of many millions of stars in the galaxy which line up to make these bars, and in computer simulations almost all galaxies will form bars really quickly. In the real world it’s been known for a long time that really strong (obvious) bars are found in about 30% of galaxies, while about 30% more have subtle (weak) bars. One of the big surprises about the Galaxy Zoo red spirals was just how many of them had bars. In fact we found that almost all of them had bars and this got the science team really curious. We followed this up with a full study of which kinds of spiral galaxies host bars using the first classifications from Galaxy Zoo 2. In this work we discovered a strong link between the colour of disc galaxies and how likely they are to have a bar – with redder discs much more likely to host bars. We now have half a dozen papers which study galactic bars found using Galaxy Zoo classifications. Put together these works are revealing the impact galactic bars have on the galaxy they live in. We have found evidence that bars may accelerate the processes which turn disc galaxies red, by driving material into the central regions to build up bulges, and clearing the disc of the fuel for future star formation.

A galactic bar is a straight feature across a spiral galaxy. It’s the orbital motions of many millions of stars in the galaxy which line up to make these bars, and in computer simulations almost all galaxies will form bars really quickly. In the real world it’s been known for a long time that really strong (obvious) bars are found in about 30% of galaxies, while about 30% more have subtle (weak) bars. One of the big surprises about the Galaxy Zoo red spirals was just how many of them had bars. In fact we found that almost all of them had bars and this got the science team really curious. We followed this up with a full study of which kinds of spiral galaxies host bars using the first classifications from Galaxy Zoo 2. In this work we discovered a strong link between the colour of disc galaxies and how likely they are to have a bar – with redder discs much more likely to host bars. We now have half a dozen papers which study galactic bars found using Galaxy Zoo classifications. Put together these works are revealing the impact galactic bars have on the galaxy they live in. We have found evidence that bars may accelerate the processes which turn disc galaxies red, by driving material into the central regions to build up bulges, and clearing the disc of the fuel for future star formation.

7. Bulgeless galaxies with black holes

Supermassive black holes are the elusive anchors in the centres of nearly every galaxy. Though they may be supermassive, they are quite difficult to spot, except when they are actively growing — in which case they can be some of the most luminous objects in the entire Universe. But how exactly they grow, and why there seems to be a fixed mass ratio between galaxies and their central black holes, are puzzles we haven’t solved yet. We used to think that violent collisions between galaxies were The Way you needed to grow both a black hole and a galaxy so that you’d end up with the mass ratio that we observe. And violent collisions leave their signatures on galaxy shapes too. Namely: they destroy big, beautiful, ordered disks, re-arranging their stars into bulges or forming elliptical galaxies. So when we went looking for pure disk galaxies with no bulges and yet with growing central black holes we weren’t sure we would find any. But thanks to the volunteers’ classifications, we did. These galaxies with no history of violent interactions yet with large central supermassive black holes are helping us test fundamental theories of how galaxies form and evolve. And we are still looking for more of them!

Supermassive black holes are the elusive anchors in the centres of nearly every galaxy. Though they may be supermassive, they are quite difficult to spot, except when they are actively growing — in which case they can be some of the most luminous objects in the entire Universe. But how exactly they grow, and why there seems to be a fixed mass ratio between galaxies and their central black holes, are puzzles we haven’t solved yet. We used to think that violent collisions between galaxies were The Way you needed to grow both a black hole and a galaxy so that you’d end up with the mass ratio that we observe. And violent collisions leave their signatures on galaxy shapes too. Namely: they destroy big, beautiful, ordered disks, re-arranging their stars into bulges or forming elliptical galaxies. So when we went looking for pure disk galaxies with no bulges and yet with growing central black holes we weren’t sure we would find any. But thanks to the volunteers’ classifications, we did. These galaxies with no history of violent interactions yet with large central supermassive black holes are helping us test fundamental theories of how galaxies form and evolve. And we are still looking for more of them!

So here’s to SEVEN more years – keep classifying!

Bars as Drivers of Galactic Evolution

Hello everyone – my name is Becky Smethurst and I’m the latest addition to the Galaxy Zoo team as a graduate student at the University of Oxford. This is my first post (hopefully of many more) on the Galaxy Zoo blog – enjoy!

So far there have been over 100 scientific research papers published which make use of your classifications, some of which have been written by the select few Galaxy Zoo PhD students (most of us are also previous Zooites). The most recently accepted article was written by Edmund, who wrote a blog post earlier this year on how bars affect the evolution of galaxies. As part of the astrobites website, which is a reader’s digest of research papers for undergraduate students, I wrote an article summarising his latest paper. Since the Zooniverse team know how amazing the Galaxy Zoo Citizen Scientists are, we thought we’d repost it here for you lot to read and understand too. You can see the original article on astrobites here, or read on below.

Title: Galaxy Zoo: Observing Secular Evolution Through Bars

Authors: Cheung, E., Athanassoula, E., Masters, K. L., Nichol, R. C., Bosma, A., Bell, E. F., Faber, S. M., Koo, D. C., Lintott, C., Melvin, T., Schawinski, K., Skibba, A., Willett, K.

Affiliation: Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064

Galactic bars are a phenomenon that were first catalogued by Edwin Hubble in his galaxy classification scheme and are now known to exist in at least two-thirds of disc galaxies in the local Universe (see Figure 1 for an example galaxy).

Throughout the literature, bars have been associated with the existence of spiral arms, rings, pseudobulges, star formation and even Active Galactic Nuclei.

Bars are a key factor in our understanding of galactic evolution as they are capable of redistributing the angular momentum of the baryons (visible matter: stars, gas, dust etc.) and dark matter in a galaxy. This redistribution allows bars to drive stars and gas into the central regions of galaxies (they act as a funnel, down which material flows to the centre) causing an increase in star formation. All of these processes are commonly known as secular evolution.

Our understanding of the processes by which bars form and how they consequently affect their host galaxies however, is still limited. In order to tackle this problem, the authors study the behaviour of bars in visually classified disc galaxies by looking at the specific star formation rate (SSFR; the star formation rate as a fraction of the total mass of the galaxy) and the properties of their inner structure. The authors make use of the catalogued data from the Galaxy Zoo 2 project which asks Citizen Scientists to classify galaxies according to their shape and visual properties (more commonly known as morphology). They particularly make use of the parameter from the Galaxy Zoo 2 data release, which gives the fraction of volunteers who classified a given galaxy as having a bar. It can be thought of as the likelihood of the galaxy having a bar (i.e. if 7 people out of 10 classified the galaxy as having a bar, then the likelihood is

= 0.7).

They first plot this bar likelihood using coloured contoured bins, as shown in Figure 2 (Figure 3 in this paper), for the specific star formation rate (SSFR) against the mass of the galaxy, the Sérsic index (a measure of how disc or classical bulge dominated a galaxy is) and the central mass density of a galaxy (how concentrated the bulge of a galaxy is). At first glance, no trend is apparent in Figure 2, however the authors argue that when split into two samples: star forming (log SSFR > -11 ) and quiescent (aka “red and dead” galaxies with log SSFR < -11

) galaxies, two separate trends appear. For the star forming population, the bar likelihood increases for galaxies which have a higher mass and are more classically bulge dominated with a higher central mass density; whereas for the quiescent population the bar likelihood increases for lower mass galaxies, which are disc dominated with a lower central mass density.

- Figure 2: The average bar likelihood shown with coloured contoured bins for the specific SFR (SFR with respect to the the total mass of the galaxy) against (i) the mass of the galaxy, (ii) the Sérsic index (a measure of whether a galaxy is disc (log n > 0.4) or bulge (log n < 0.4) dominated and (iii) the central surface stellar mass density. This shows an anti-correlation of

with the specific star formation rate. The SSFR can be taken as a proxy for the amount of gas available for star formation so the underlying relationship that this plot suggests, is that bar likelihood will increase for decreasing gas fraction.

Bars become longer over time as they transfer angular momentum from the bar to the outer disc or bulge. In order to determine whether the trends seen in Figure 2 are due to the evolution of the bars or the likelihood of bar formation in a galaxy, the authors also considered how the properties studied above were affected by the length of the bar in a galaxy. They calculate this by defining a property , a scaled bar length as the measured length of the bar divided by a measure of disc size. This is plotted in Figure 3 (Figure 4 in this paper) against the total mass, the Sérsic index and the central mass density of the galaxies. with the population once again split into star forming (log SSFR >-11

) and quiescent (log SSFR < -11

) galaxies.

As before, Figure 3 shows that the trend in the star forming galaxies is for an increase in for massive galaxies which are more bulge dominated with a higher central mass density. However, for the quiescent population of galaxies,

decreases for increasing galactic mass, increases up to certain values for log n and

and after which the trend reverses.

The authors argue that this correlation between and

within the inner galactic structure of star forming galaxies is evidence not only for the existence of secular evolution but also for the role of ongoing secular processes in the evolution of disc galaxies. Furthermore, they argue since the highest values of

are found amongst the quiescent galaxies (with log n ~ 0.4) that bars must play a role in turning these galaxies quiescent; in other words, that a bar is quenching star formation in these galaxies (rather than an increase in star formation which has been argued previously). They suggest that this process could occur if the bar funneled most of the gas within a galaxy, which is available for star formation, into the central regions, causing a brief burst of star formation whilst starving the majority of the outer regions. This evidence becomes another piece of the puzzle that is our current understanding of the processes driving galactic evolution.