First X-ray Data of the Mergers with Chandra

I just got notice from the people at the Chandra Science Center that Chandra has executed the observation of the first Galaxy Zoo merger – part of our study to understand black holes in mergers. This is the first of twelve such observations that should take place over the next year or so. The main science question we have that this program will help us answer is: in how many mergers do both black holes feed?

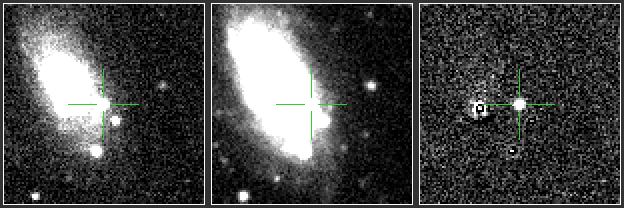

All I have at the moment are the quick-look data that that they sent me. They are more or less raw images. Here is the full frame:

And here is a zoom-in:

This is raw data, rather than properly analyzed data, so we can’t really draw any firm conclusions based on it yet, but it seems like there is no significant source detected. What does that mean? Assuming that there really is no source after we properly analyze the data, then the black hole(s) in this particular merger are either not feeding very much, or they are hidden behind lots of gas and dust.

For now, we will wait for the actual data to fully analyze it, and for the remaining 11 targets to be observed.

Radio Peas

Working with scientists in India, we have been awarded time on the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT) to study the radio properties of the Green Pea galaxies discovered by Galaxy Zoo users. We hope to use this telescope to detect the first signs of radio emission from the Peas, establishing them as a new class of radio sources.

Why do we want to search for radio signals from the Peas? The radio emission comes from remnant supernovae which can accelerate relativistic electrons that emit synchrotron radiation. So when we are detecting star forming galaxies in radio emission, we are finding signatures from these supernovae, which tell us about the stars that live (or lived) in the galaxy. Therefore, using the radio emission we can trace recent star formation activity in the galaxy.

We are particularly interested in these Green Peas, because they are the closest analogues to a class of vigorously star forming galaxies found in the early universe (known as Lyman Break Galaxies). These galaxies behaved very differently from star forming galaxies in the present day universe, and can help us to understand how galaxies formed in the early universe. Because Lyman Break Galaxies are so far away, Astronomers have not yet been able to detect radio emission from any of these galaxies individually. In contrast, the Peas are much closer and we have a good chance of being able to directly detect them in radio emission. Detecting this radio emission, and determining whether or not the radio emission from the Peas is like that in nearby star forming galaxies will help us to understand the nature of star formation in the youngest galaxies.

Supernova zoo offline this week

Just to let you know that the supernova zoo will be offline for most of this week. The search that feeds data to us, the Palomar Transient Factory, is undergoing some maintenance. They’re re-aluminising the mirror of the telescope to improve the sensitivity, which usually takes a few days during which the telescope can’t be used. (It’s also the beginning of “bright time”, coming up to full moon, when the sky is brighter and the search less sensitive – so it’s a good time for maintenance.)

So, you can all take a well-deserved break from the supernova classifications.. and perhaps explore some other areas of the zooniverse which need your help! We’ll be back in a few days.

Supernova updates

Hello from the William Herschel Telescope, where I’m observing some of those lovely supernova candidates that have been pouring out of The Supernova Zoo lately.

It’s been a while since our last update. We’ve been running supernova zoo in a very serious way now for several months, and, after ironing out a few little bugs and adding some improvements, the zoo is making a massive contribution to the supernova identification effort in The Palomar Transient Factory. The zoo has already classified some 20,000 supernova candidates, usually several hundred every day; it’s a fabulous effort. You’ve classified every supernova candidate that we’ve put in the zoo!

We also hope that you’re beginning to see feedback on the supernova candidates that you spend your time classifying (at least the better ones!). From this current observing run I’ve been adding comments as I classify the events that you’ve highlighted, so you might see them appearing in your “MySN” area (of course, the more you classify, the more likely this is to happen!).

Here are some of your nice recent finds, all Type Ia Supernovae.

This one seems to live in a galaxy located in a cluster of galaxies:

This is one in a nearby NGC galaxy – the SN is located directly in one of the spiral arms.

And this one is also in a spiral galaxy – but one that is more edge on:

We’re currently preparing a scientific publication that will detail supernova zoo and how it works – and we also have plans to add a new survey to give you even more supernova to play with. So stay tuned!

OK, my exposure has just finished, so I’ll sign off here and go and see what the latest supernova candidate turned out to be!

— Mark

Observing Red Galaxies With VIRUS-P

Hi Zoo fans,

My name is Peter Yoachim and I’m currently a postdoc working in the Astronomy Department at the University of Texas in Austin.

I got involved with the Galaxy Zoo after I saw Karen’s paper on Red Spirals. When I first read the paper I thought, “Wow, that’s really cool, spirals shouldn’t look red like that, wonder what happened to those galaxies.”, followed shortly by, “OMG, we have the perfect instrument to make follow-up observations of these objects!”

While I’ve been at UT, I’ve been making extensive use of VIRUS-P (Visible Integral-field Replicable Unit Spectrograph Prototype), a new instrument at McDonald Observatory in West Texas. Right now, VIRUS-P is mounted on the 2.7m Harlan J. Smith telescope. While modest in size by current standards, the 2.7m has been a scientific workhorse since 1968 although it is probably most famous for having several bullet holes in the primary mirror.

As I tell my 101 students, images of the sky are a great starting point, but if you want to do Astrophysics, you need to observe some spectra. With galaxies, the full spectra can tell us how different parts of the galaxy are moving (via the redshift and blueshift of light), what kind of stars are in the galaxy, and if there is any hot gas present. VIRUS-P is great for getting spectra, especially for targets like nearby galaxies.

In the bad old days (like when I was doing my thesis work 6 years ago), it was common to pass light from the telescope through a narrow slit, then bounce it off a grating to disperse the light onto the detector to observe the spectrum. The problem is that the narrow slit blocks most of the light from the galaxy. This is a tragedy! That light traveled for (literally) millions of years only to bounce off the slit mask at the last second.

Rather than use a long slit, VIRUS-P uses a fiber-optic bundle to pipe the light around. Here’s an example from a recent paper. NGC 6155 is just a nice normal galaxy, here’s an image of it from the Sloan survey:

When I observe the same galaxy with VIRUS-P, I see this:

Each circle represents a fiber. I’ve color-coded the fibers so that the brightest spectra are blue and the faintest are red. This isn’t too fancy, it even looks quite a bit worse than the Sloan image. But look what happens if I calculate the velocity from the redshift of the spectra in each fiber:

Now we can see the rotation of the disk. The top left of the galaxy is moving away form us, while the bottom right is moving towards us. The redshift of light only shows us the part of the motion that happens to be along our line of sight, but that’s still enough to get a good idea of how the stars and gas in the galaxy orbit the center. The next trick is to add up the spectra from multiple fibers to build up the signal to make it possible to measure accurate ages for the stars.

What we see here is the center of the galaxy is old (~7 billion years), while the disk is young and still forming stars (average age ~4-6 billion years). The youngest section that’s 4 billion years old corresponds to the bright blue spiral arms in the Sloan image. The cool part is the very outskirts of the disk are made of very old stars (8-10 billion years old), a result some of my coauthors actually predicted.

It should be clear now how VIRUS-P will be great for observing the red spirals. We can compare the motions of red spiral disks to regular spirals, and we can measure stellar ages to try and determine when star formation shut off in these galaxies.

The observing of the red spirals has been done by intrepid UT graduate student John Jardel. With the remnants of hurricane Alex blowing through, the observatory has received excessive rain this summer. All that rain makes it hard to observe, plus it lets the rattlesnakes and scorpions thrive. Here’s a scorpion I caught in the observatory lodge last week:

Despite the weather and wildlife, John was able to observe 5 galaxies. We’ve just finished our last observing run of the season, so we haven’t had a chance to analyze the data yet. But looking at the raw images, we already see something interesting:

The horizontal stripes are the signal from each individual fiber. The bright vertical lines are emission lines from the earth’s atmosphere. The two circles show 5 fibers where we can see bright spots. Those spots are emission from hot Hydrogen gas in the galaxy. If there’s gas, it’s possible these red galaxies could start forming stars again and turn back to regular blue spirals. Since the gas is hot and in emission, it could even be the case that there is star formation going on right now.

Chandra Program to study Galaxy Zoo Mergers approved

Good news, everyone!

Earlier this year we submitted a proposal to use the Chandra X-ray Observatory to observe a set of merging galaxies in X-rays. The target list for Cycle 12 has just been released, and with a bit of scanning, you can find a set of targets with names like “GZ_Merger_AGN_1”. These targets are a set of beautiful merging galaxies discovered by YOU as part of Galaxy Zoo 1 and the Merger Hunt. The 12 approved targets are here:

These 12 mergers are all very pretty, but they have something else in common: they all host active galactic nuclei (AGN) – feeding supermassive black holes at their centers. X-rays are great for finding such hungry black holes, but we already know that all 12 of these mergers are AGN, so why observe them again? We’re looking for a mythical rare beast: the binary AGN!

Only a handful of these objects are known and they were discovered by chance. We believe that every massive galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its center and so when two galaxies merge, then there should be two black holes around for a while, that is, until they merge. The goal of our Chandra study of these 12 mergers is to systematically search for binary AGN in merging galaxies to work out what fraction of them feature two feeding black holes. Knowing whether such phases are common or not is important for understanding how black holes interact with galaxies in mergers and what exactly happens to them as they plunge towards the center of the new galaxies where they are doomed to merge and form a single supermassive black hole.

As usual, it may be quite a while before we get the data. The observing cycle won’t start for a while and takes about a year. Since our observations are short and we don’t have any time constraints (they’re galaxies, they don’t move!) the Chandra operators will most likely schedule our observations in between longer projects and time sensitive observations and so we won’t know when they will happen. Of course, once we do get the data, we’ll definitely update you.

Oh and you might notice some of the targets in the Merger Zoo in the near future. We’ll need your help to fully understand them….

A Kitt Peak gallery

Here are some pictures from the recent Kitt Peak observing run, illustrating the experience beyond just our data collection (as interesting as that was, and continues to be). Collecting these was easier than usual since I had colleagues at the telescope, so I could run off and shoot pictures from the dome’s catwalk without worrying about the telescope. Kitt Peak is home to over 20 telescopes – not just those operated by the National Optical Astronomy Observatories, but additional ones operated under tenant agreements by the University of Arizona and consortia of other institutions (plus the Kitt Peak visitor programs running 3 30-40 cm telescopes of their own). You can see many of them strung along the summit in this view from the southwest. From left to right, they are the Mayall 4m, University of Arizona’s Bok 2.3m 0.9, and Spacewatch 1.8m, SARA 0.9m, 0.9m Burrell Schmidt, Calypso Observatory 1.3m, WIYN 3.5m, public 0.35m, WIYN 0.9, Kitt Peak 2.1m, and the tower of its coude feed telescope. (These will not be on the quiz).

Our visit started with a night onsite at the 0.9m SARA telescope, a rarity since it is usually operated remotely from one of 10 partner institutions. We were training some summer research students there, so they could have a better understanding of what happens when they clock those virtual buttons. Here is the telescope itself, and a twilight view under the stars.

At the 2.1m telescope, Drew checks to make sure the primary mirror is still there. Fortunately it was, so we could go about our observations without having to explain something quite this bizarre to the management.

The CCD we were using to detect the spectra works most efficiently when cool – really cool. Its kept in contact with a bath of liquid nitrogen, that had to be refilled every 12 hours. You know it’s full not when vapor pours out of three ports behind it, but when droplets of liquid nitrogen can be heard hitting the floor. That plastic face shield seemed like a better and better idea.

The action naturally picks up around sunset – make sure your internal calibration measurements are finished, open the dome to let the inside and outside air come to equilibrium for best image quality.

Of course, with solar telescopes on the mountain, you get really impressive views of the sunset from there. One of these shows an airplane – could be an airliner over California, or a large military plane over a training range closer to the west; the air was too turbulent to tell.

As each night progresses, the Moon waxed from a fingernail-shaving crescent to an annoyingly bright gibbous phase. For the first few nights, moonset was just an interesting spectacle.

Later it became a marker for when we could look for fainter galaxies and get better data without the interference of moonlight in the sky.

Similarly, the phase of the moon affects not only our data, but the whole view of the night sky. In so-called dark time, we could watch the Milky Way rise only once did we sit on the catwalk munching Milky Way bars while doing this). The lights the distance are mostly from the Mexican city of Nogales, Sonora, just over the border. It is much larger than the twin town of Nogales, Arizona (which I think is an important place because that’s where my wife was teaching when we met. But I digress.)

As the Moon waxed, the view of the mountaintop changed – the domes cold be seen along with great numbers of stars if there was just the right amount of moonlight.

I always find it a very evocative view to see a telescope silhouetted against the stars, and keep trying to get a picture that adequately captures the feeling. This was my latest attempt.

The 2.1m telescope shares a building with the Coude Feed Telescope, an arrangement which allows the smaller 0.9m feed mirror to direct light into the giant room-filing code spectrograph when it’s not used by the main telescope. Here, you see that telescope’s fixed primary mirror at the top of a separate tower and the moving flat mirror which feeds it starlight. In the distance is the striking peak known as Baboquivari, which plays a central role in the lore of the Tohono O’Odham people (on whose land and by whose permission Kitt Peak National Observatory is located).

The coude spectrograph fills a large tilted room below the telescope. Here is one of its diffraction gratings, about 60 cm across.

Just before dawn each night, we were in the right place to see the Hubble Space Telescope pass high in the south. Here is its trail emerging from behind the 2.1m dome – from one 2-meter telescope to another!

Dawn’s glow first mingled with the lights of the city of Tucson about 50 km away (adorned here by the Pleiades as well just before they vanished for the day).

We also took the time to visit a bunch of the astronomical neighbors, but that can be a post for another day…

Operations at Kitt Peak

Hello from Kitt Peak again everyone. We are now more than half way through our observing run, everything is going really great, we are getting lots of spectra of our candidate galaxies. So far we have managed to do most of our top priority candidates!

Bill gave us a great post of what we are up to and some of the results we have taken so far. I wanted to talk a little bit more about the practical aspects of observing, to give you guys a feel for a typical night up here at the 2.1 meter. We have taken a lot of pictures and a few videos of the experience. Click the video thumbnails to watch each one.

Each night starts about 6pm, roughly an hour before sunset. Before we can do any of the fun stuff we have to get the telescope ready, this involves quite a few steps. The telescope itself is an amazing pice of kit but shares pretty much the same design as most telescopes since Newton’s time. Big curved mirror at the bottom, small mirror up the top, hole in the bottom mirror to let the light out again. It’s essentially a bit light bucket, catching photons which have been traveling happily and uninterrupted through space for billions of years.

The real technology lives at the bottom of the telescope, where your eye would normally go. On our telescope we have Gold Cam, a spectrograph and camera which allows us to analyse the light from galaxies and Voorwerpjes alike. By splitting up their light in to all its component colours, we can tell a great deal about each object, from how far away it is to what kind of atoms make it up and what state these atoms are in . To get the best out of this system however we need to prepare and calibrate it each night. The first thing we have to do is get the system nice and cold. Actually we need to keep it cold at all times, and when I say cold I mean cold. Your fridge freezer at home is probably about -10 degrees celsius, the coldest ever recorded temperature in the Antarctic was −89.2 °C, we have to keep the camera at a staggering -150 °C !!

To do this we cool it down with a supply of liquid nitrogen which we have to top up every 12 hours or so. Each afternoon, before we start observing and again in the morning before we leave, we attach a hose from a dewier to the bottom of the telescope and fill her up. If we didn’t do this then the camera would heat up to unacceptable levels and would have to go away for quite a lot of work before it could be used again.

Once we are sure that the telescope is going to stay nice and chilly we settle in to the observing room. This is adjacent to the main telescope dome and is where we will spend most of the night. To get a feel for where we work I made a quick video tour:

Sorry about the quality I had to use my laptop’s webcam to take it.

The first job of the night is to calibrate all our instruments. The measurements we are trying to obtain are very precise and so we need to make sure that we understand the response of our sensors. Imagine your personal digital camera fell in the bath one day, or was smashed against a wall or something to make it go a bit funny. In this mishap the sensor has got messed up, it still works but when you take a picture with it one side is a lot darker than the other. Instead of throwing the camera out you could try to correct for the damage. If you knew exactly the pattern of light and dark patches you could make some pixels brighter and some dimmer to compensate. So how do you figure out that pattern? Well you could take an image of a totally white background, or an image of something where you knew the exact value that every picture should have.

We do exactly this on the telescope each night, its called “flat fielding”. We also take calibration images of a special lamp which is built in to the telescope. This lamp makes a known pattern in the spectrograph and so lets us correct for any other issues we might have.

Having cooled and calibrated the system we are almost good to go. We look up the coordinates on the sky of the object we are interested in and slew the telescope round to point at it. As the earth rotates around its axis the stars appear to move slowly across the sky. It takes 24 hours for the stars to go all the way round and end up where they started, which may seem slow to us but for a telescope like the 2.1 meter, which is magnifying the field of view a lot, this movement is actually very quick. If we just left the telescope pointing in the same direction, the galaxy we are interested in would quickly move out of the telescope’s view. So we have motors which rotate the telescope in the opposite direction to the Earth’s motion, to keep the telescope pointed at the same patch of the sky. This process isn’t perfect, however, and the galaxy can still drift away if we are not careful.

Thankfully the telescope has another trick up its sleeve, if we find a bright star near to the galaxy we are interested in, we can ask the telescope to move in such a way that this star always appears in the same place. We call these stars guide stars and before we can take data we have to find one and lock on to it. That’s the theory at least; our system has been a bit temperamental this week. Occasionally we have to do things the old fashioned way, manually adjusting where the telescope points to keep the fuzzy blob which is our galaxy centered.

Each of the galaxies we are looking at are very faint. So faint that to gather enough light, even with a telescope as large as this one, requires us to stare at the galaxy for anywhere between 45 and 60 minutes. It’s quite a long time where there isn’t much to do appart form keep an eye on the galaxy, shoot the breeze, chew the fat and plan our next target. On particularly long exposures we have become fond of nipping up to the catwalk that runs along the side of the dome to take in the view. The Milky Way here is the best I have ever seen it! . You can see our bursts of activity in this time lapse of the observing room… we are not just slacking off… honest.

Once the exposure is done we move to a new object, but before we do we need to take yet another calibration exposure. This one is to make sure the position of the telescope isn’t causing the spectrograph and camera to flex out of shape, altering our reading. We also need to rotate the spectrograph to get the slit through which the light enters, in to the right orientation for what we want to look at.

We repeat the same process about 6/7 times a night and hopefully get 6/7 fresh galaxy spectra. Initially we can only tell a little from the data, we wont really get results until all those calibration test are combined with the galaxy spectra. Its a long, careful and very tedious process known as reduation, thankfully one which isn’t mine … its Drews.

At the end of each night, as the sun comes up about 4pm, we have to put the telescope to bed. This involves swinging it back round to its initial position and closing up the main mirror. With that done we can all go to bed as well, to dream sweet dreams of Voorwerpjes.

Wanted – interesting targets for Kitt Peak spectra!

As noted on this forum post, we’re starting to run out of Voorwerpje candidates at the end of the night (because that’s the part of the sky that gets put of the SDSS imaging area). We’re asking for suggestions – so post your ideas and tell us why they’re interesting on the forum thread!

(This offer expires on June 20. Not valid where restricted or prohibited by law. Employees and relatives of Galaxy Zoo personnel are pretty much great people and are welcome to chime in. Observers’ decisions are final no matter how compromised by sleep deprivation.)

Hunting Voorwerpjes from Arizona

We have a team working at Kitt Peak again, this time using a spectrograph to chase down Voorwerpjes. As the Dutch diminutive indicates, these are like Hanny’s Voorwerp, only smaller. They are clouds of gas within galaxies (or out to their edges) which are ionized by a luminous active galactic nucleus. In most of these, unlike Hanny’s Voorwerp, we can see other signs of the active nucleus, but the same considerations of hidden versus faded are important. Zooites have given us a rich new list of potential objects, many from the special object hunt set up by Waveney incorporating database queries done by laihro, and more from reports on the Forum. They often show up as oddly-shaped blue zones on the SDSS images, when strong [O III] emission lies in the SDSS g filter. At some redshifts, they look purple, when Hα enters the i filter.

I’m also working with four summer students from the SARA consortium at our 0.9m telescope, normally operated remotely but this time hands-on. (Last night was the first time I’ve ever operated its camera while in the same building as the telescope). One of these students , Drew, is spending the summer working on Voorwerpjes, and is also working on the spectra. Our first night here was devoted just to training at the SARA telescope.

Last night we started at the Kitt Peak 2.1m telescope with a long-slit spectrograph known as GoldCam (for its color). For each galaxy, we’ve used whatever previous data were available – SARA images, processed SDSS data, a few observations by other people – to work out the most informative direction to align the spectrograph slit, which then delivers data all along that line on the sky. To set the orientation, we physically rotate the spectrograph on the back of the telescope, taking care not to snag any of the cables. This made it interesting when there was a failure of the hydraulic platform we usually use to get to the spectrograph – it’s been ladders and flashlights to do this tonight. We have a luxurious span of 7 nights (although they are practically the shortest of the year), so we can plan a pretty extensive study. We needed to concentrate on one spectral region for best sensitivity and spectral resolution, so we are using the blue range (3400-5400 Angstroms). For the redshifts of these galaxies, that lets us measure the strong [O III] emission lines and look for the highly-ionized species He II and [Ne V]. These two species are signposts that the gas is irradiated by the UV- and X-ray-rich spectrum of a quasar or Seyfert nucleus, not a star-forming region. Our first task is to conform that this is the case for many of our candidates. Beyond that, the ratios of the emission lines tell us how dense the gas is in each region, and how strong the ionizing ultraviolet is. That, in turn, suggests whether the nucleus has remained at about the same luminosity over the timespan that its light took to reach these clouds, and whether it is hidden from our view by dense absorbing material. The most exciting cases may the the galaxies that seem to have [O III] clouds but no optical AGN; they could be additional examples of the kind of rapid fading from an active nucleus that we believe went on with IC 2497 and Hanny’s Voorwerp.

One of the galaxies I most wanted to see spectra from is UGC 7342, among the greatest hits of the forum and Voorwerpje hunt. It has roughly symmetric regions of highly ionized gas reaching 45,000 light-years from the nucleus on each side, which the images suggested were probably ionization cones. These are the result of radiation escaping the nucleus only in two conical regions on opposite sides (around a thick obscuring disk). This phenomenon is seen in some other type 2 Seyfert galaxies, and if the cones are pointed in another direction, we don’t expect to see deep into the nucleus directly. These pictures were done with the SARA telescope (as I sat in my den with the cats). From left to right, they show [O III] emission, Hα emission, and the starlight alone as seen in a red filter (which has been removed from the emission-line images).

We aligned the slit with the long axis of the emitting gas (and just about across the bright star at lower left). This paid off spectacularly. Here’s a first look at a 45-minute exposure from earlier tonight. Wavelength increases from left to right, and the bright streak across the bottom is the foreground star’s spectrum. At the wavelets of such lines as Hβ and [O III], the gas glows across a huge region around the galaxy (extending vertically in this display), lit up by an active nucleus which is partially hidden from our viewpoint.

This is a chance to mention how we (truth in advertising, mostly Drew over the last couple of weeks) have been using the SDSS images to narrow down the most likely candidates for [O III] clouds and get their exact locations for the spectrum. For objects with very strong emission lines in only one or two SDSS filters, we can use one of the other filters as a guess for what the starlight of the galaxy would look like in one of the emission-line filters. We subtract various amounts of this estimate from the filters with [O III] and Hα, and select the one that isolates the clouds best. It’s not perfect, since stars in different parts of galaxies may have different average colors, but does a pretty good job as a screening tool for these active galaxies.

We want to look not only at the best candidates, but a representative set of all kinds that have turned up. This includes “purple haze” a fairly shapeless glow combining the colors of [O III] and Hα, which we see almost solely around the brilliant nuclei of type 1 Seyfert galaxies. This may be what an ionization cone looks like when we look down its axis.

We’re coordinating what we do with three nights coming up in July using a double spectrograph at the 3-meter Shane telescope of Lick Observatory, being carried out by Vardha Bennert. The telescope is larger and the instrument can get good resolution in blue and red simultaneously, so that it makes sense for us to treat some of what we do now as a screening study which can be followed up next month. (Vardha checked a couple of our candidates during a slow part of the night last December, and confirmed a purple-haze object as genuinely large emission-line clouds. This allayed my concern that these might be artifacts of incomplete registration of the three SDSS filters going into color images).

We’re still going, with six more nights and an encouraging weather forecast…