A Grand Bold Thing : The story of the Sloan

In many ways, the team here at Galaxy Zoo are freeloaders, making the most (with your help) of the hard work of the astronomers who work hard for years to design, build and operate the telescopes that produce the images for us to classify. The project’s first two incarnations were based entirely on images from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, the star of A Grand Bold Thing, a book that was released this week.

Several Zookeepers were interviewed for the book, and while I don’t know for sure that we made the final cut I asked the author, Ann Finkbeiner to explain why she’d devoted so much of her time to writing about the Sloan. Over to Ann :

My book on the Sloan Digital Sky Survey — the source of those galaxies in Galaxy Zoo and the mergers in Galaxy Zoo Mergers — came out yesterday. The Sloan was, and still is, the only systematic, beautifully-calibrated survey of the sky and everything in it. And it’s the first survey to be digital, that is, log on to the website and download galaxies.

Before the Sloan, cosmology was fractured into many fields whose relation to each other wasn’t obvious and wasn’t being studied. Sloan found all kinds of things in all areas of astronomy: asteroids in whole families, stars that had only been theories, star streams around the Milky Way, the era when quasars were born, the evolution of galaxies, the structure of the universe on the large scale, and compelling evidence for dark energy. Now, after the Sloan, cosmologists are beginning to see the universe as a whole, as a single system with parts that interact and evolve.

A Grand and Bold Thing is about the very human scientists who built the survey: people doing their best, screwing up anyway, fixing it, screwing up again, running into trouble with the young folks, running into trouble with the money, getting their feelings hurt, forming hostile camps, and managing the unintended consequences of their best intentions. But they never give up, they’re astonishingly stubborn, they just keep at it until they’ve done it.

And what they did has had an enormous impact: as Julianne Dalcanton

of the University of Washington said in the blog, Cosmic Variance, about the Sloan, “You take good data, you let smart people work with it, and you’ll get science you never anticipated.” Some of that science is being done by the good people of the Zooniverse. Surveys open to the public have always been high altruism. I think the Sloan is still surprising.

Ann Finkbeiner’s last book was The Jasons. She teaches in Johns

Hopkins University’s Writing Seminars and blogs at Last Word on

Nothing.

Galaxy Zoo gets highlighted by the 2010 Decadal Survey

Every decade, the US astronomy community gets its leaders together to write up a report on the state of the field and to recommend and rank major projects that should be supported by the government over the next decade. It’s a blue print, a wish list and often also a sober exercise in what to fund (a little) and what to cut (a lot). The current Decadal Survey was finally released by the US National Academies last Friday and every astronomer is poring over it to see if their project or telescope is ranked highly.

Galaxy Zoo isn’t competing for hundreds of millions of dollars in funding to launch a space observatory, but it did get not just one but two mentions in the 2010 Decadal Survey, one in the text and a figure. For those of you who are keen to read the whole thing for themselves, you can get the report at the National Academies website here (you have to click on download and give them your details to get the free PDF download). Here on the blog we only show you the highlights, i.e. the Galaxy Zoo mentions. From the text in the section on “Benefits of Astronomy to the Nation” where they discuss how “Astronomy Engages the Public in Science”:

Astronomy on television has come a long way since the 1980 PBS premier of Carl Sagan’s ground-breaking multipart documentary Cosmos. Many cable channels offer copious programming on a large variety of astronomical topics, and the big three networks occasionally offer specials on the universe too. Another barometer of the public’s cosmic curiosity comes from the popularity of IMAX-format films on space science, and the number of big-budget Hollywood movies that derive their plotlines directly or indirectly from space themes (including five of the top ten grossing movies of all time in America). The internet plays a pervasive role for public astronomy, attracting world-wide audiences on websites such as Galaxy Zoo (www.galaxyzoo.org, last accessed July 6, 2010) and on others that feature astronomical events, such as NASA missions. Astronomy applications are available for most mobile devices. Social networking technology even plays a role, e.g., tweets from the Spitzer NASA IPAC (http://twitter.com/cool_cosmos, last accessed July 6, 2010).

They also have a lovely figure, which has a small blooper in it (see if you can spot it!). Word is that this is going to be corrected in the final version:

Thank you all for making Galaxy Zoo such a success!

Edwin Hubble, the man behind HST

Who is Edwin Hubble, the guy who gave the Hubble Space Telescope its name? Who is the mysterious guy behind the telescope?

Edwin Hubble

Well, actually, Edwin Powell Hubble is not the ‘man behind the telescope’ at all. He was born on 20th of November 1889 in the US and studied Physics and Astronomy in Chicago. He then, interestingly, went to Oxford, UK (now, of course, one of the main departments participating in Galaxy Zoo), to study Jurisprudence, later Spanish. Given that he was also very sporty (he won several state track competitions and set the state’s high school high jump record in Illinois), I think it is fair to call Hubble a person with multiple talents. In England, he also picked up some English habits and his dress code, some to the annoyance of his american colleagues in later years. I don’t know many pictures of him, the one on the right is possibly the most famous (usually used in scientific talks at least). Smoking his pipe on his desk, he really looks like an English gentlemen of his time (Well, maybe he’s lacking a hat).

Edwin Hubble died on September 28th 1953 in California (his house is now a National Historic Landmark at this location), long before the real planning for the HST had begun. Earlier ideas did exist, since 1923, after it was explained how a telescope could be propelled into Earth orbit and in 1946, Lyman Spitzer (who interestingly enough has his own space telescope named after himself now) had already discussed the advantages (which I will discuss in the next post about the planning of the HST) of an extraterrestrial observatory, but it took until 1962 for the US NAS (not NASA!) to recommend the development of a space telescope for other purposes than observing the sun (two orbiting solar telescopes were in fact already active at that time). In 1965, 12 years after Hubbles death, Spitzer was appointed head of the committee to define the scientific objectives for this new telescope, so really, he is the ‘man behind the Hubble Space Telescope’.

So why is the telescope named after Edwin Hubble then?

After some years of teaching at the university back in the US and after serving in WWI as a major, he returned to the Yerkes Observatory at the University of Chicago, where he finished his Ph.D. in 1917. The topic of his thesis was ‘Photographic Investigations of Faint Nebulae‘ (it only consists of 17 pages, a fact that possibly makes every PhD student cry nowadays). At that time, these nebulae were still considered to be part of the Milky Way, something that was waiting for a real genius and careful observer to be revealed as a mistake.

The Hooker Telescope

In 1919, Hubble took on a staff position in California at the Mount Wilson Observatory near Pasadena where he stayed until his death in 1953. Just 2 years previously, a new telescope had been finished at the site, the Hooker telescope (the slightly unfortunate name comes from John D. Hooker who funded the project), a 100-inch Reflector telescope, which today is still there and, after some recent upgrades and modifications (although preserving the historical origin wherever possible), is again used for scientific purposes. With its ‘adaptive optics’ system (see next post) its resolution today is 0.05 arcsec, the same as resolution of the HST. From 1917 to 1948, the Hooker telescope was the world’s largest telescope.

Hubble used this new, state-of-the-art telescope to continue the work on nebulae that he had started in Chicago by identifying Cepheid variable stars in them. Cepheids have the very convenient characteristic, that the period of their variability is a simple function of their brightness. So by measuring their period, astronomers can immediately tell how bright these objects are in a standard system. Measuring their apparent brightness allows to measure their actual distance. By doing this, Hubble noticed that they are far too distant to be part of our own galaxy, but instead are extragalactic systems, islands of stars (and possibly life) in the vast nothingness of space. Other distant ‘Milkyways’, just like our own.

We now call them ‘galaxies’.

Being some of the closest galaxies to our own, most of the objects that he worked on are now very famous, some also through images by the HST. The most famous of all is possibly M31, the closest big galaxy to our own, the Andromeda galaxy, or what Hubble called it, the Andromeda Nebula.

The original version of the Hubble diagram

Additionally to his distance measures of 46 galaxies Hubble further took measurements from Vesto Slipher of their escape velocity. This is basically the speed with which ‘the galaxies move away from Earth’ (what we now understand to be the cosmological redshift) and can be relatively easily measured by looking at the galaxies’ spectra, in which all spectral lines, previously known from lab experiments, are shifted by the same amount. When Hubble plotted the escape velocity of galaxies over their distance (we call this a Hubble diagram), he noticed something interesting:

The further galaxies are away from our position, the faster they move away.

This was a pretty radical idea as it proved that the Universe is not a static place at all as was widely believed before. For example, Einstein had introduced an additional term into his cosmological formula in general relativity to make his universe static/non-dynamical (something Einstein called the biggest blunder of his life after he had seen Hubble’s data. Funnily enough, this constant is now back in there to explain the accelerated expansion of the universe. It resembles the ‘dark energy’). Instead, this effect means that either the Earth is in a very special spot of the Universe where everything is flying away from it (a thought that many people, amongst them Einstein, considered wrong. The hypothesis that there is nothing special about the place where the Earth is other than that it is where we happen to live, is one of the basic fundamentals of cosmology) or there was a time in the past when everything was at the same point, much like in an explosion. Of course, we now know it was not an explosion in the traditional sense, but the beginning of time, the Big Bang.

Of course, as with most big new discoveries, these new findings were heavily discussed, not many people believed in them in the beginning. One after another, people started believing in Hubbles results, though, and the view that astronomers have on the universe changed completely. The Big Bang Theory (besides being a brilliant TV series) is now the generally accepted picture today.

As a small anecdote on the side: Due to errors in his distance measurements, Hubble measured the expansion parameter (the Hubble constant) to be 500 km/s/Mpc, which for today’s measurements is a pretty bad value, actually. After new, better data and improved data analysis were used, there were 2 big groups of people debating the real value, some said it was 50 km/s/Mpc, some others said it was 100 km/s/Mpc. For the past 10-15 years, this battle seems solved Solomonically, the value is now assumed to be just inbetween these values, somewhere between 70 and 75 km/s/Mpc. So, although Hubble was very wrong in the number that came out of his measurements, he somehow got the principle spot on.

Using the images that he had taken for his work, Hubble also came up with a system to classify these nebulae and galaxies depending on their appearance. This is what we call the Hubble sequence or the tuning fork of galaxies, and Galaxy Zoo initially used a system that was based on this diagram for their classifications.

As the Hubble Space Telescope was primarily constructed and built to observe distant galaxies (besides of course looking at objects in the solar system and interesting regions in our own galaxy), it was named after Edwin Hubble in honour of his groundbreaking work in this field.

Edwin Hubble has not only got a Space Telescope with his name, but several laws, constants and numbers are named after him, too.

Some examples:

- The Hubble constant as explained above, called H0

- The Hubble time is 1/H0 and gives the approximate age of the universe. It is currently estimated to be around 13.8 billion years.

- The Hubble length is c/H0and is equivalent to 13.8 billion lightyears. This is not the ‘size’ of the universe, but is an important length in cosmology

- The Hubble diagram as described above

- The Hubble sequence of galaxies.

- Hubble’s law

Additionally, there are:

- An asteroid: 2069 Hubble

- The crater Hubble on the Moon.

- Edwin P. Hubble Planetarium, located in a High School in Brooklyn, NY.

- Edwin Hubble Highway, the stretch of Interstate 44 passing through his birthplace of Marshfield, Missouri

- The Edwin P. Hubble Medal of Initiative is awarded annually by the city of Marshfield, Missouri – Hubble’s birthplace

- Hubble Middle School in Wheaton, Illinois—renamed for Edwin Hubble in 1992.

- 2008 “American Scientists” US stamp series, $0.41

(I think when they make you a stamp and you’ve got your own highway, you’ve really made it!)

I think that’s more or less all that I can come up with about Eddi, the post is actually quite a bit longer than I thought it would be, I’ll try to keep it shorter in the future, scout’s honour. For now, I will end with a quote from Edwin Hubble:

“Equipped with his five senses, man explores the universe around him and calls the adventure science”

With this, keep together your senses, especially seeing (the galaxies in Galaxy Zoo) and feeling (your mouse button with your index finger) and help us to do more adventurous science with the classified galaxies that you help us with (hearing, smelling and tasting are only of second order importance in astronomy, unless of course you listen to some music and have a snack while classifying 😉 ).

Thanks and Cheers,

Boris

Me, HST and the history of surveys

Before I start with a new series of posts, please let me introduce myself.

My name is Boris Häußler (look at my horribly out-of-date website here). I am German but currently working as a research fellow in Nottingham, UK, where I have just recently started my second postdoc with Steven Bamford, whom many people here may know. I have spent the last years (actually, my whole scientific life so far) working on Hubble Space Telescope (HST) data, mainly on the GEMS and STAGES surveys, and have gathered particular experience in the field of galaxy profile fitting, trying to measure sizes, shapes, etc. of distant galaxies. Whereas my previous projects have mainly been working on galaxies at redshift z~0.7, my new job is trying to do similar and more advanced things on more local galaxies, mainly SDSS galaxies, which of course everyone familiar with Galaxy Zoo will know as these are the galaxies classified in both Galaxy Zoo and Galaxy Zoo 2. Initially, one would think that this is a much easier job to do, but as this data is from ground-based telescopes, it proves to be challenging.

This brings me to an interesting position. Although Galaxy Zoo is not my primary science project, I am now connected to the survey through Steven, our galaxy sample and (for now) more directly through this blog. Having worked on HST galaxies for ages, it is of course very interesting for me to see these galaxies now being classified in Galaxy Zoo: Hubble. Having created some of the colour images that both GEMS and STAGES have used for outreach purposes, I have looked at thousands of these galaxies myself and know how stunningly beautiful they can be. I very often got lost on our images, simply browsing around and being fasctinated by the variety of the galaxies. At least in GEMS I know many galaxies by heart and could possibly directly point you to at least some of the brighter and/or more interesting galaxies.

This brings me to an interesting position. Although Galaxy Zoo is not my primary science project, I am now connected to the survey through Steven, our galaxy sample and (for now) more directly through this blog. Having worked on HST galaxies for ages, it is of course very interesting for me to see these galaxies now being classified in Galaxy Zoo: Hubble. Having created some of the colour images that both GEMS and STAGES have used for outreach purposes, I have looked at thousands of these galaxies myself and know how stunningly beautiful they can be. I very often got lost on our images, simply browsing around and being fasctinated by the variety of the galaxies. At least in GEMS I know many galaxies by heart and could possibly directly point you to at least some of the brighter and/or more interesting galaxies.

Being kind of an HST expert, Steven has asked if I would want to write a series of posts about HST, an offer that I found hard to turn down, so I’ve decided to write quite a long series about the HST, its history, its future and especially introducing some of the bigger HST surveys, some of which of course build the content of Galaxy Zoo: Hubble now. But before I write and post all this, I would be interested to know what people would actually want to know about Hubble and everything connected with it. So if you have any comments, any wishes, any questions, please post them below and I will try to answer them in the future.

My current plan for the next months contains the following posts, roughly running through the history of Hubble in chronological order:

- Who is Edwin Hubble, the man that gave HST it’s name?

- History of Hubble, the planning and the start 20 years ago

- HST gets spectacles, first service mission

- HDF, the Hubble Deep Field, the first famous survey,

- Another service mission, putting new cameras (e.g. ACS) on HST

- GOODS, the Great Observatories Origins Deep Survey

- GEMS, Galaxy Evolution from Morphologies and SED

- AEGIS , the Deep Extragalactic Evolutionary survey

- HUDF, the Hubble Ultra Deep Survey, the deepest survey ever made

- STAGES, Space Telescope Abell901/902 Galaxy Evolution Survey

- COSMOS, the Cosmic Evolution survey

- The service mission to put in another camera (WFC3)

- Upcoming surveys: CANDELS

- The Future of HST

- HST’s successor, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)

If you want to know about anything else, please let me know below.

Thanks and Cheers for now,

Boris

From Voorwerp to webcomic – the quest continues

This weekend, we’re trying to make as much progress as we can toward producing the webcomic “Hanny and the Quest of the Voorwerp”, a NASA-supported public-outreach effort. Pamela (AKA starstryder) and Bill are at CONvergence in Minneapolis, Minnesota, meeting with writers and artists. In Galaxy Zoo style, we’ve invited people who want to help write it to get involved at three daily working sessions here (with professional writer Kelly McCullough doing the final editing and organizing), then passed onto the artist and colorist. We’ll swap passages with our views of the proceedings.

You can also follow us on Twitter @hannysvoorwerp

Day 0 & 1 (Bill)

I got an early start yesterday, getting here in time to give a seminar on Hanny’s Voorwerp (and its smaller relatives) to the astronomy department at the University of Minnesota. This is usually a good way to bounce ideas off colleagues that I don’t see all the time.

I thought ahead and arrived at CONvergence today properly attired for our sessions.

We were scheduled in a room used at other times for science demos and kids’ programs; it’s full of such interesting things as M.C. Escher floor puzzles, tornado demonstrators, and robot parts. Pamela had prepared a set of poster-sized prints for the participants’ reference – a picture gallery, cast of characters, and some of the ground rule for the project. After today’s session these went up on the wall outside the meeting room for further reference (along with one of the small posters advertising the sessions), creating a Voorwerp Wall.

We went over some of the early discovery events with some new prospective writers. Tomorrow we hope to get deeper into the story and how to tell it in the most engaging way that suits such a visual medium. Stay tuned for updates…

Days 0 & 1 (Pamela)

Like Bill, I got here yesterday. It was a 7:10am flight out of St Louis and clear flying via O’Hare to Minneapolis airport (a home of terrible coffee and effective luggage carousels). My trip here is being paid for by the Women Thinking Freely Foundation in association with the Skepchicks, so I’m having a blast bouncing between panels on science, skepticism, podcasting, and the Voorwerp.

One of the traditions of this particular Con is plastering the hotel with posters promoting events, so yesterday did my bit to paper the planet and posted our poster almost everywhere. The reason I saw almost is because I discovered several walls where someone had beat me to the punch – printing our promotional posters and hanging them ahead of time. I don’t know who it was, but if I can find them, I want to give them a giant thank you. It was just awesome to come across voorwerps in the wild.

Today was more panels, and the opportunity to meet our writers. The group of us gathered around Bill and my laptops, and in many ways it was story-telling hour as we cast the quest for understanding into comic book form. The telescopes became oracles (who sometimes deigned to give us knowledge, and sometimes rejected our petitions for an audience), and in one moment of brainstorming (not to make it into the comic) we had Comic-Book-Hanny Hanny looking at the Voorwerp and asking “What’s that?” while the Voorwerp looked back asking the same thing of all of us humans looking at it. It’s fun playing with language and ideas, even if we have to sometimes toss out the fun ideas to make sure we tell a true and scientific story. Tomorrow we meet again, at 11am central, and we’ll be twittering as we go.

Our goal is for all the writers to get their work done by a week from today (with a few pages to hopefully take back to our awesome illustrators (Elea Braach & Chris Spangler) by the end of this weekend.

This all feels a bit like running with scissors, but I think if we trip, we’re only in danger of cutting up the stereotype that science is boring.

Day 2 (Bill)

This was a real workday on the project – we attracted a couple of new participants, and got into details of how to depict key events, and thinking about what visual scenes captured important moments. I am especially partial to Stephane Javelle’s discovery of IC2497 back in 1908 visually, using the 75-cm refractor at Nice – which translates in today’s comic vocabulary to a 10-meter hunk of steampunk. We liked the idea that Kevin’s thesis advisor should appear only as a hulking , ominous shadow from an offstage figure, and the notion of a globe with word balloons in 5 places all making excited noises when the email announcing Hubble time came out. It will still be a challenge to tell the reader the important things about spectra while keeping the flow and not bogging down in detail.

This photo shows chief wordsmith Kelly McCullough (left) using the posters to bring a couple of new potential writers up to speed on the story so far.

Voorwerp Web-Comic: Authors meeting at CONvergence

Have you ever looked at the Voorwerp and said to yourself, “Doesn’t that look like the Swamp Thing?” Or maybe you’ve seen Kermit the Frog dancing, or a maybe you see foliage run amok. There is just something about the Voorwerp that make me, for one, want to anthropomorphize it as a monster, and I’m betting some of you have had the same moment of Pareidolia.

The neat thing about the Voorwerp is it not only looks like the character from a bad monster movie, but it is a real-life monster of a problem that has played a starring role in an intellectual adventure. While astronomy doesn’t normally get turned into summer block buster movies, this story just might make it with a rating of “S: Judged appropriate for people who contribute to science in their spare time.”

Image with me – you go into a movie theatre and hear booming from the speakers: “It came on the 13th; Monday the 13th. And one woman dared to ask ‘What is that stuff?'” Suddenly the camera zooms in on the Voorwerp. Then this imaginary movie trailer has us cutting between action adventure shots of astronomers racing for telescopes (you see a car racing across the desert with domes in the distance), the Swift space telescope repointing, and Zoo Keepers conferring in solemn tones as they gather around a computer. Bill Keel (played by Martin Sheen?) asks, “Can we get Hubble time?” and someone played by the Hollywood hunk of your choice responds in an overly dramatic tone, “I don’t know, but we have to try – I want answers – and we can handle the truth.”

Ok, so maybe the idea is pure cheese, and no Hollywood director (or college film major) is likely to shoot this flick, but there is still a story here that is worth sharing with the world.

And the STScI agrees with us. They’ve funded the creation of a digitized comic book (a web comic) to tell the story of Hanny’s discovery of the Voorwerp and the scientific adventure all of us have gone on as the truth has been sought in all sorts of wavelengths using a myriad of telescopes.

This comic is being written under the guidance of Kelly McCullough (author of the Ravirn series) by a team of volunteer writers at the CONvergence Con outside of Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA. The writers will work in close collaboration with Bill Keel and many other Zoo Keepers to make sure they get the story completely right.

Want to watch? Want to hang out with Zoo Keepers (list of attendees to come) at a cool event? Then join us in Bloomington, Minnesota, July 1-4, 2010. The event does cost money, unfortunately, and you have to register (My turn to bring the cookies). The cost of registration goes up May 15, so if you’re interested, please register ASAP for lowest prices.

We’ll be releasing the comic at Dragon*Con in the fall. We’d love it if you’d consider coming and being part of the celebration.

We’re going to work to keep you informed about everything that is going on. You can follow along at http://hannysvoorwerp.zooniverse.org, and in the webcomic thread on the forums.

60 Million Classification Giveaway

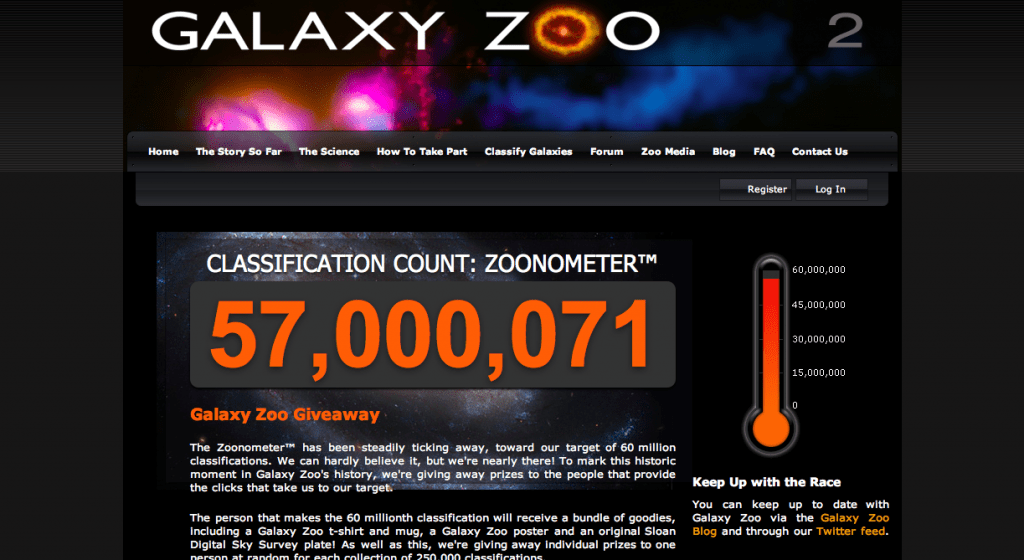

Yesterday, Galaxy Zoo launched a fun little competition to mark the approach of our 60,000,000th classification. This is the point at which we can create an amazing and powerful database from the Galaxy Zoo 2 data.

Galaxy Zoo’s ticking clock of classifications, The Zoonometer™, has been steadily ticking away, toward our target of 60 million classifications for a long time. We can hardly believe it, but we’re nearly there! To mark this historic moment in Galaxy Zoo’s history, we’re giving away prizes to the people that provide the clicks that take us to our target.

The person that makes the 60 millionth classification will receive a bundle of goodies, including a Galaxy Zoo t-shirt and mug, a Galaxy Zoo poster and an original Sloan Digital Sky Survey plate! As well as this, we’re giving away individual prizes to one person at random for each collection of 250,000 classifications.

The prizes kicked off with the 57,000,000th classification, which was achieved last night at about 2100 UT (see extremely geeky screenshot). One of the 250,000 classifications that led us to the 57,000,000 mark will now be selected at random to win a Galaxy Zoo mousepad. We will also be picking a winner from the 57,000,000 – 57,250,000 range as well. The winners will be posted on the Zoonometer™ page. We are appaoraching 57,500,000 as I type this.

If you want to take part, all you have to do is what you do best: classify galaxies! It will also help if you make sure you’re Zooniverse email address is up to date so we can contact you if you’re a winner.

60 Million Target Explained

With 60,000,000 classifications in the database, the Galaxy Zoo 2 project will have reached a critical point. 60 million classifications represents our minimum, ideal database. With that many classifications you, the participants, will have collectively classified every galaxy enough times to create an incredibly robust, well-defined and scientifically valid catalogue of Sloan galaxies. Beyond the 60 million classifications, every additional click still goes into the database – it just means that our minimum science goal is achieved.

What is an SDSS Plate?

The person who classifies the 60 millionth galaxy will win an original Sloan Digital Sky Survey plate. These plates are quite large and make amazing memorabilia, since they were actually used to observe galaxies by the SDSS. We are lucky enough to have one of these plates at Zooniverse HQ, to give away. 640 holes have been drilled into the plate, with each hole corresponding to the position of a selected galaxy, quasar or star in the sky. During observations, scientists plug the holes with optical fibre cables. The fibres simultaneously capture light from the 640 objects and record the results in CCDs. The plates are interchangeable with the CCD camera at the focal plane of the telescope. You can read more about how the SDSS performed observations on their own webpages.

Ring of the Week: The Eagle Has Landed

“Fly me to the moon

Let me play among the stars

Let me see what spring is like

On a-Jupiter and Mars”

– Frank Sinatra, “Fly Me to the Moon”

This week I had the honour of meeting three legends of the 20th century; astronauts Capt. Neil Armstrong, Capt. Gene Cernan and Capt. Jim Lovell. Neil Armstrong is, of course, the first man to set foot on the moon (Apollo 11), Jim Lovell was the commander of Apollo 13 and Gene Cernan was the last man to walk on the moon (Apollo 17).

Right to left: Capt. Gene Cernan, Capt. Neil Armstrong and Capt. Jim Lovell

The astronauts were talking on behalf of the Foundation for Science and Technology at the Royal Society and Cernan and Lovell both spoke of their disappointment at the US plans to abandon the “Constellation” programme which aimed to put astronauts back on the moon by 2020. Cernan said that, walking on the moon in 1972, he never would have imagined that he would still be the last man to set foot on the moon’s suface over 37 years later. The astronauts also talked of their hope that they would be alive to see man set foot on Mars.

Politics aside, it was fascinating to hear the astronauts speak about their experiences. All of the astronauts agreed that travelling to the moon changed their perspective of life on Earth. Cernan said it was staring out of the window into the black “infinity of space”, whereas Lovell said it was looking back from the moon and “being able to cover the entire World with my thumb” that was the most life changing moment.

My Ring of the Week this week is Galaxy Zoo image 587741708326863123 and is in honour of Neil Armstrong and his lunar module, the Eagle. You can see the ring on the bottom right of the image and an unusual, bird-shaped “Eagle” galaxy on the top left. The “Eagle” galaxy is at the same redshift as the ring and so at the same distance away from us. This means that the two galaxies are most likely interacting in some way.

My Ring of the Week this week is Galaxy Zoo image 587741708326863123 and is in honour of Neil Armstrong and his lunar module, the Eagle. You can see the ring on the bottom right of the image and an unusual, bird-shaped “Eagle” galaxy on the top left. The “Eagle” galaxy is at the same redshift as the ring and so at the same distance away from us. This means that the two galaxies are most likely interacting in some way.

It could be that the “Eagle” is a polar ring (see last week’s post), where stars have been gravitationally stripped from the larger ring galaxy to rotate around the poles of the smaller galaxy. Or perhaps this is a collisional ring system, the “Eagle” having crashed through the centre of the larger galaxy to create the blue ring of stars that we see on the bottom right of the image. At the moment I’m not quite sure exactly which option (if either!) is the right one so feel free to post your own ideas about what you think may be happening and I’ll let you know if I figure it out!

Ring of the Week: Arp 87

“Up on a hill, as the day dissolves

With my pencil turning moments into line

High above in the violet sky

A silent silver plane – it draws a golden chain

One by one, all the stars appear

As the great winds of the planet spiral in

Spinning away, like the night sky at Arles

In the million insect storm, the constellations form

On a hill, under a raven sky

I have no idea exactly what I’ve drawn

Some kind of change, some kind of spinning away

With every single line moving further out in time”

– Brian Eno, “Spinning Away”

Well if you ask me, what you’ve drawn there Brian is a “Polar Ring” galaxy.

Polar ring galaxies, unlike all other galaxies in the Universe, are made up of two distinct parts. In the centre we have a normal galaxy and around the outside we have a “golden chain” of stars and gas clouds. This ring is perpendicular to the “silver plane” of the host galaxy disk, rotating over the poles, and so it’s known as a polar ring.

So how are polar rings formed? Polar rings are thought to form when two galaxies gravitationally interact with each other. We believe that “one by one, all the stars appear” as they are stripped from a passing galaxy and “spiral in” to produce the polar ring we see today. Polar rings, although not quite as rare as smoke rings, are pretty hard to find. According to “New observations and a photographic atlas of polar-ring galaxies”, about 1 in every 200 lenticular galaxies (a type of galaxy between an elliptical and a spiral) have these “golden chains” of stars and gas spinning around them. Below is a selection of some of my favourite polar rings from the Galaxy Zoo:

The Zooites have done fantastically well at finding Polar Rings and you can see all of their incredible finds on the Possible Polar Ring thread on the Galaxy Zoo forum.

The Zooites have done fantastically well at finding Polar Rings and you can see all of their incredible finds on the Possible Polar Ring thread on the Galaxy Zoo forum.

My Ring of the Week this week is the stunning pair of interacting galaxies Arp 87. Located in the constellation Leo, approximately 300 million light years away from Earth, Arp 87 gives us a fantastic insight in to exactly how polar ring galaxies are formed. The image on the left is the Galaxy Zoo Arp 87 image and on the right is an image taken by the Hubble Space Telescope. We can clearly see the galaxy on the left gravitationally stripping away the stars and gas from the spiral galaxy on the right.

Unfortunately for Brian Eno, his hypothesis of a “golden chain” of stars that “spiral in” a “silver plane” came a full 23 years after the first polar ring galaxy was identified by J. L. Sérsic in 1967.

However, perhaps someone else had already had a genuine polar ring premonition a full 78 years before Sérsic’s discovery…?

– “Starry Night” 1889, Vincent Van Gogh

The Hubble image is part of a collection of 59 images of merging galaxies released on the occasion of its 18th anniversary on April 24, 2008. (NASA, ESA, the Hubble Heritage (STScI/AURA)-ESA/Hubble Collaboration, and A. Evans (University of Virginia, Charlottesville/NRAO/Stony Brook University))

Ring of the Week: Arp 147

“Then take me disappearin’ through the smoke rings of my mind

Down the foggy ruins of time…

Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free,

Silhouetted by the sea, circled by the circus sands,

With all memory and fate driven deep beneath the waves,

Let me forget about today until tomorrow.”

– Bob Dylan, “Mr Tambourine Man”

After last week’s leisurely cruise through 450 million light years to Mayall’s Object, this week I take you on a flying tour across the local Universe to view the spectacular galactic jewels known as “Smoke Rings”.

Smoke Rings, like all collisional ring galaxies, are formed when a smaller galaxy hits bull’s-eye into the centre of a larger disk galaxy. The impact creates a density wave, throwing matter out into a ring shape. With the help of the Zooites I’ve found just 12 Smoke Rings in the Galaxy Zoo and so these amazing objects are very rare indeed. You can see 4 of them below:

There are two things you’ll notice about these galaxies:

Firstly, all of the smoke rings we’ve found are blue in colour. This is because as the shock wave expands into the disk, it triggers the birth of large numbers of high mass stars. Massive, young stars are extremely hot and so the light that they radiate is bright blue.

Secondly smoke rings, by definition, have no central nucleus. Answering the question of why smoke rings have no obvious nucleus is not as simple as it may sound but we believe that smoke rings are created in one of the following situations:

- The original target galaxy had no substantial nucleus to start with

- Or the angle and position of impact was such that the nucleus was thrown out into the ring

- Or the nucleus was destroyed by the impact

Smoke rings are incredibly important as they are shining blue clues as to how galaxies collide. My Ring of the Week this week is Arp 147 – a perfect example of the way that smoke rings allow us to turn back the clock and stare deep into the Universe’s distant past.

Arp 147 is located in the constellation Cetus over 400 million light years from Earth. The image on the left is the Galaxy Zoo Arp 147 image and on the right is an image taken by the Hubble Space Telescope. We can clearly see the “bullet” galaxy on the left and, on the right, the bright blue ruins of the original “target” galaxy. What makes Arp 147 so special is the unusual reddish-brown spot at the bottom of the ring and we believe that this marks the exact position of the original nucleus of the “target” galaxy. From the positions of the bullet, the smoke ring and the red spot we can rewind time over millions of years and simulate exactly how these two galaxies collided.

So as we “dance beneath the diamond sky” it is the smoke rings, beautiful in their simplicity, that make the “foggy ruins of time” crystal clear.

The Hubble image is part of a collection of 59 images of merging galaxies released on the occasion of its 18th anniversary on April 24, 2008. (NASA, ESA, the Hubble Heritage (STScI/AURA)-ESA/Hubble Collaboration, and A. Evans (University of Virginia, Charlottesville/NRAO/Stony Brook University))