101: The Great Debate

This is the first in a new series of blog posts under the title of ‘Galaxies 101’. These posts aim to explore the history and basics of the science of galaxies. I’ll be covering some of people who helped us understand these ‘Island Universes’ as well as some of the basics that would be taught during a first year undergraduate galaxies course at university.

It is fortunate that these posts are beginning in the week of the 90th anniversary of The Great Debate which occurred on April 26th, 1920. The Great Debate – or the Shapely-Curtis Debate – took place at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History between two eminent astronomers, Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis. Shapely was arguing that the ‘spiral nebulae’, that were observed at the time, were within our own Galaxy – and that our Galaxy was the Universe. He also argued that the Sun was not at its centre. Conversely, Curtis argued that the Sun was at the centre of our Galaxy but that the ‘spiral nebulae’ were not inside our Galaxy at all. He suggested instead that the Universe was much larger than our Galaxy and that these nebulae were in fact other, ‘island’ universes.

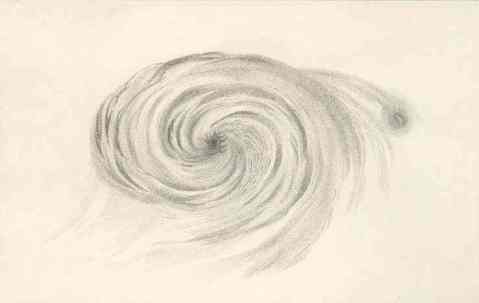

Below is a drawing of the ‘spiral nebula’ M51. This is an observation by Lord Rosse, drawn in 1845 using the 72-inch Birr Telescope at Armagh Observatory in the UK.

With 90 years of hindsight we can now say that Shapely and Curtis were both right and wrong. The Sun is not at the centre of the Galaxy and the Galaxy is only one of hundreds of billions of galaxies in the Universe. But how was the argument resolved? The answer, in part, comes from a very famous name in astronomy: Hubble.

Less a decade after the Great Debate took place, Edwin Hubble used the largest telescope in the world – the 100-inch Hooker Telescope on Mount Wilson – to observe Cepheid variable stars in the Andromeda Nebula/Galaxy. Cepheid variables are a type of pulsating stars whose pulsation periods are precisely proportional to their luminosities. This makes Cepheid variable stars a ‘standard candle’ – an object where the brightness is a known quantity. If you can observe the apparent brightness of a standard candle, then you can determine its distance by a simple inverse square law. Since Cepheid variable stars have pulse rates proportional to their luminosity, if you can measure the pulse rate of a Cepheid variable anywhere in the Universe, then you can determine how far away it is. This is what Edwin Hubble did in 1925 and he calculated the distance to Andromeda as 1.5 million light years.

At the time, Shapely thought that our Galaxy was around 300,000 light years across and Curtis believed it was around 30,000 light years. Hubble’s measurement placed Andromeda well outside our galaxy and showed that Curtis was correct in thinking that the ‘spiral nebulae’ could indeed be other galaxies. Today we think the Milky Way is about 100,000 light years across and that Andromeda is 2.5 million light years away.

The discoveries of the 1920s started a whole new adventure for astronomy. The Universe had gotten a lot bigger and was about to expand much, much more. It is important to remember that Shapely, although wrong about the nature of the nebulae, did correctly assert that the Sun was not at the centre of the Galaxy. This is the kind of Copernican shift that makes people think about things differently and it is important to realise that the issues discussed during the Great Debate were complex. For our benefit though, the Great Debate is a starting point for exploring the relatively new study of galaxies. Humanity’s view of the Universe, and our place within it, has changed an awful lot since 1920. The study of galaxies has had a lot to do with that.

If you want to read more about the Great Debate, and what else helped to resolve the arguments I can recommend this excellent NASA site. You can also read the published text of the debate online.

[Andromeda image credit: Robert Gendler]