Looking for bars in faraway galaxies

Hi all! My name is Tobias Géron, I’m a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Toronto. I’ve been using Galaxy Zoo for a few years now to study bars in galaxies.

Bars seem to be very common structures in the present-day Universe, with roughly half of all disc galaxies having a bar. Bars are also thought to influence their host galaxies in all kinds of fun ways (e.g. see some previous blogposts here and here). The quintessential barred galaxy is NGC1300, which flaunts a beautiful long bar in its centre that connect to its spiral arms.

As some of you may know, we recently classified images from the CEERS survey in an iteration of Galaxy Zoo called GZ CEERS. These images were taken by JWST, an amazing telescope in space that excels at taking pictures of galaxies that are really far away. Due to the finite nature of the speed of light, looking at faraway galaxies means that we are also looking back in time. Astronomers quantify this with a property called “redshift”. A redshift of 0 corresponds to the present-day Universe, while higher redshifts means looking back further in time. This allows us to study how common bars are over time.

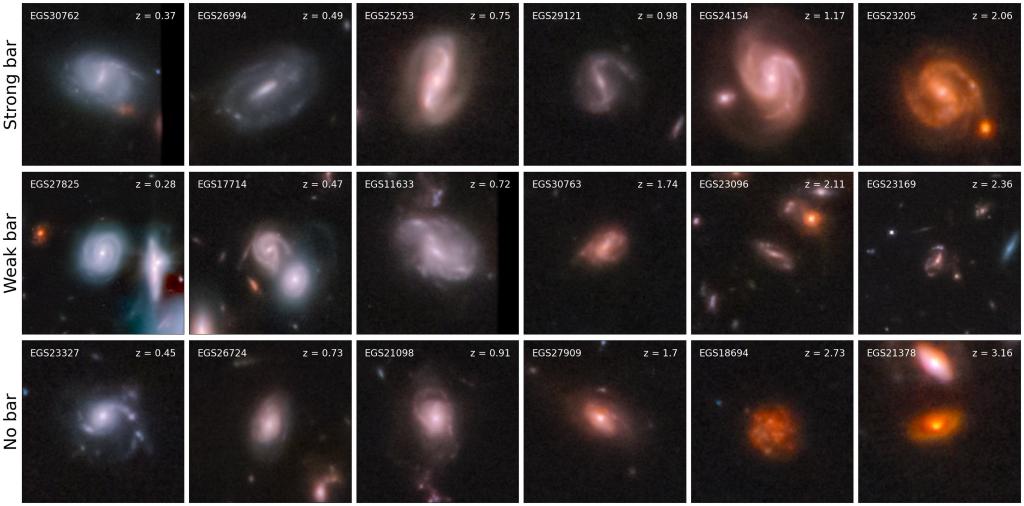

Using data from GZ CEERS, we tried to study bars up to a redshift of 4. This sounds a bit abstract, but it corresponds to looking back roughly 12 billion years in time! The Universe is only ~13.7 billion years old, so we are able to study bars over most of the history of the Universe. How cool is that? Without further ado, here are some cool pictures.

The top row shows galaxies where we found really long and obvious bars. The middle row shows shorter and less obvious bars, while the bottom row shows some unbarred galaxies. My personal favourite is the one in the top-right corner, EGS23205. This galaxy has an absolutely beautiful bar. What’s even crazier is that this galaxy is found at a redshift of ~2, which corresponds to a lookback time of ~10 billion years.

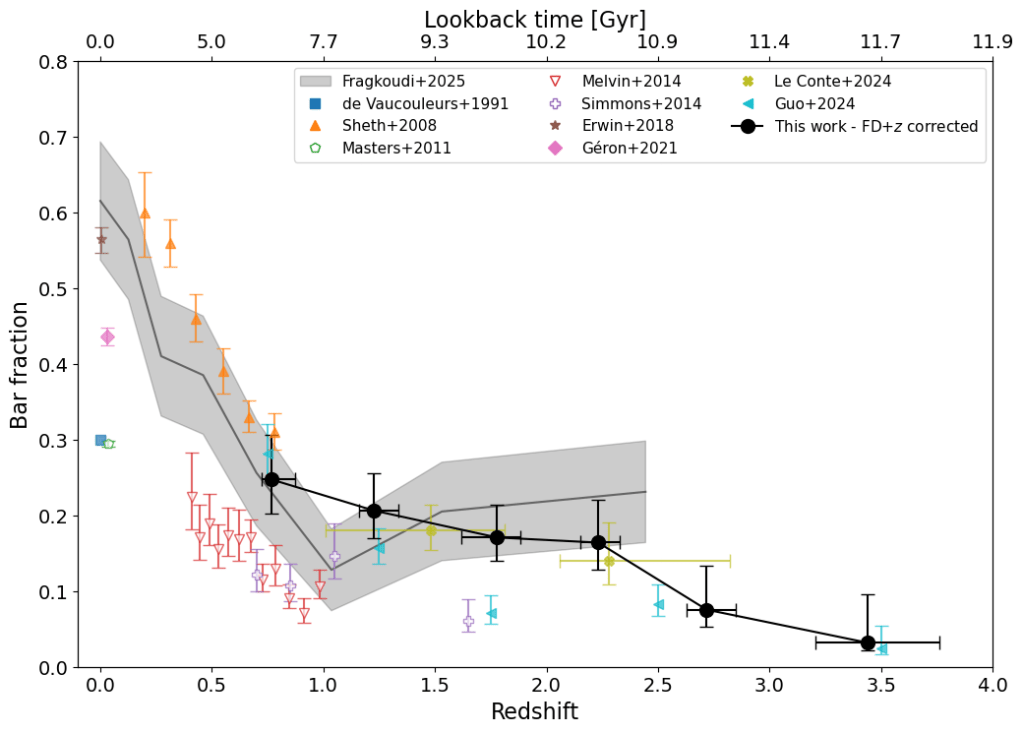

Great – so we now have found bars at high redshifts. However, in order to do some science, we want to know what fraction of galaxies host such bars at any given redshift. This is shown in the image below.

The full black line shows the redshift evolution of the bar fraction found using GZ CEERS. Our bar fractions agree with those obtained from simulations, which are shown with the grey contours (Fragkoudi et al. 2025), as well as some other studies looking at the bar fractions at high redshifts (Le Conte et al. 2024 and Guo et al. 2024). I’ve also added the results of some lower redshift (z < 1) studies to complete the whole picture.

The main conclusion from this plot is that this line is decreasing; i.e. there are fewer bars at higher redshifts. This is consistent with the picture that most galaxies start without a bar. At the highest redshift probed (z = 4), fewer that 5% of disc galaxies have a bar. Over time, more and more galaxies form bars, to such an extent that in the present-day Universe, roughly half of all disc galaxies have a bar!

This has a lot of implications for the evolution of galaxies, as well as the formation and lifetime of the bars themselves. All of this has just recently been published in Géron et al. (2025). We go into much more detail of how the barred galaxies were found, how observational corrections were applied, as well as the implications for galaxy evolution, bar formation and the lifetimes of bars.

In conclusion: bars are awesome. There seem to be a lot of them out there, even at very high redshift. They influence the evolution of galaxies in the local Universe, and are likely a significant contributor to the evolution of galaxies at high redshifts as well. Stay tuned for more exciting upcoming results from GZ CEERS!

Cheers,

Tobias