GZ1 used for the fractions of early-types in clusters

We’re happy to report that we have once again used your (now public) GZ1 classifications to find an interesting result.

We use the classifications in a study we just submitted to MNRAS (or see the arXiv entry for a copy) looking at the observed fractions of early-type galaxies (and spiral galaxies), in groups and clusters of galaxies.

Recent work (De Lucia et al. (2011), which posted to the arxiv in September), used sophisticated semi

analytic models to determine the properties of galaxies found in massive

clusters in the Millennium Simulation. They identified elliptical galaxies

(or more accurately early-type galaxies) in the simulation, and found that the fraction these

galaxies, remained constant with cluster halo mass, over the range 10^14 to

10^14.8 solar masses. They compared their results with previous

observational studies which each contained less than 100 clusters.

With GZ1 we realised we could put together a much larger sample. We

used galaxies with GZ1 classifications, cross matched with cluster and

group catalogues, to compare the above results with almost 10 thousand

clusters. We found that the fraction of early-type galaxies is indeed

constant with cluster mass (see the included figure), and over a much larger range of 10^13 to 10^15

solar masses (with covers small groups of galaxies to rich clusters), than previously studied. We also found the well known result (to astronomers) that outside of groups and clusters, the fraction of early-type galaxies is

lower than inside of groups and clusters.

Plot showing the fraction of early-type galaxies (red lines) as a function of halo mass. We used two different halo mass catalogues, and the agreement between them is excellent. We also examine the fraction of spiral galaxies with halo mass (blue lines)

This work suggests that galaxies change from spiral to early-type when individual

galaxies join together to form small groups of galaxies, but that going from groups to rich clusters does not significantly change the morphologies of galaxies.

Without the GZ1 results at our finger-tips, this work, which was devised,

implemented, and written up in less than 2 months, would have taken much

longer to complete.

Thanks again for making the Zoo such a wealth of information,

Ben Hoyle (on behalf of Karen Masters, Bob Nichol, Steven Bamford, and Raul Jimenez)

First look at Hubble's first look at the first Voorwerpje

The bits are still warm, having just been downlinked from Hubble overnight. There is still a good bit of processing to be done, cleaning up cosmic rays and so forth. But that said, here is our first look at SDSS 2201+11, first of the Galaxy Zoo AGN cloud galaxies (AKA voorwerpjes) to come up on the telescope’s schedule. As a reminder, as waveney just posted in yesterday’s Object of the Day, here it is in the SDSS images:

And now what we’ve all been waiting for! First up, the galaxy in a narrow filter that includes the strong [O III] emission from the clouds at this redshift:

emission”]![Hubble image of SDSS 2201+11 with [O III] emission](https://blog.galaxyzoo.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/sdss2201-hsto3.jpg?w=479)

And one in a filter including H-alpha emission, which is several times fainter in such highly ionized gas:

And finally, in the tradition of vacation photographs everywhere, a shot of just the galaxy (in this case a medium-width filter near the standard i band to show the stars and dust but not the gas):

First inspection shows that the galaxy has been disturbed – the dust lanes twist. One of them trails right off into one of the gas clouds, adding to our evidence that ionized tidal debris often shows up in this way. That also suggests which cloud is on the near side, so we have a clue about the time delays experienced by the radiation we see from each one as it has been affected by possible changes in the nucleus. There are interesting holes and curlicues in the gas, as well.

Further processing will show us more. And there are six galaxies to go! (These should dribble in throughout 2012 – we just got an appetizer).

How to Navigate the Astro Literature, Part 1

So you want to learn about current astrophysics research? You’re in luck! Not only are there many excellent blogs, pretty much all of the peer reviewed literature is out there accessible for free. In many areas of science, the actual papers are behind paywalls and very expensive to access. Astrophysics, like a few other areas of physics and mathematics, puts most papers on the arxiv.org preprint server where they are all available for download form anywhere. In addition, we have a very powerful search tool in the form of the NASA Astrophysics Data System which allows you to perform complex searches and queries across the literature.

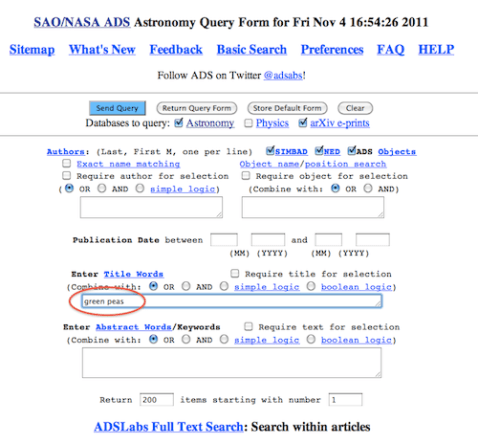

Suppose you wanted to learn more about the green peas, one of our citizen science-led discoveries. Your first stop could be the ADS:

ADS, like any search engine, will now scour the literature for papers with the words “green peas”, “green” and “peas” in it, and return the results:

As you can see, the discovery paper of the peas, “Cardamone et al. (2009)” is not the first hit. That’s because in the meantime there has been another paper with “green peas” in the title. You can click on Cardamone et al. and find out more about the paper:

This is just the top of the page but it already contains a ton of information. Most importantly, the page has a link to the arxiv (or astro-ph) e-print (highlighted). Clicking there will get you to the arxiv page of the paper where you can get the full paper PDF.

Also there is a list of paper which are referencing Cardamone et all, at the moment 23 papers do so. By clicking on this link you can get a list of these papers. Similarly, just below, you can get a list of paper that Cardamone et al. is referencing.

Lower still are links to NED and SIMBAD, two databases of astronomy data. The numbers in the brackets indicate that SIMBAD knows 90 objects mentioned in the paper, and NED knows 88. By clicking on them, you can go find out what those databases know about the objects in Cardamone et al. (i.e. the peas).

Obviously there’s a lot more, but just with the arxiv and NASA ADS you can search and scour the astrophysics literature with pretty much no limits. Happy resarching!

Voorwerpjes – results now ready for prime time!

Yesterday marked a milestone in the Galaxy Zoo study of AGN-ionized gas clouds (“voorwerpjes”), when we received notice that the paper reporting the GZ survey and our spectroscopic study of the most interesting galaxies

has been accepted for publication in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. We’ve now posted the preprint online – at http://arxiv.org/abs/1110.6921 on the preprint server, or, until publication, I have a PDF with full-resolution graphics. Here’s the front matter:

The Galaxy Zoo survey for giant AGN-ionized clouds: past and present black-hole accretion events

Read More…

Update on the "Violin Clef" merger: redshifts and Merger Zoo

Hi everyone,

Since I haven’t posted here before, I’d like to introduce myself. My name is Kyle Willett, and I’m a postdoc working at the University of Minnesota in Lucy Fortson’s group. My work for Galaxy Zoo includes development of the next generation of tools that Zooites can use to explore galaxies and conduct their own research. My own scientific focus is on high-energy active galaxies, for which our group is using Sloan and Galaxy Zoo data to try and quantify the environmental properties.

For this post, I’d like to talk about follow-up work we’ve been doing on a recent discovery. About a month ago, Galaxy Zoo contributor Bruno discovered an example of a spectacular merger in the Sloan DR8 data that looked like a triple, or possibly quadruple system. It’s been informally dubbed the “Violin Clef” or the “Integral” based on its shape:

SkyServer image: http://goo.gl/qhFRc

This system is scientifically interesting for several reasons. While merging galaxies are common throughout the universe, the merging process is relatively quick compared to the total lifetime of a galaxy. Catching a system with long tails and multiple companions is rarer, and gives us the chance to match our models of galaxy interaction against a system “caught in the act”. This is one of the main drivers of Merger Zoo, and a system like this is a good test to see if we can reproduce the tidal features. If so, then we can start to think about the bigger picture, and predict how often you’d expect a multi-galaxy merger like this to occur.

We’re also interested in the gas and stellar content of the galaxies and their tails. In most merging systems, gas in the galaxies is gravitationally compressed, which leads to a burst of new star formation in the galaxies and their tails. Since this results in more young and hot stars, the colors of these galaxies are typically blue in the Sloan bands. However, all four galaxies and the tidal tails in this system are red. If that’s the case, then we want to estimate the current age of the system. Were the galaxies all red ellipticals to begin with, with very little gas that could form new stars? Or has the starburst already come and gone – and if so, how long-lived are these tidal tails going to be?

After Bruno’s discovery, the team started by looking at what other archived observations could tell us. An ultraviolet image from the GALEX satellite showed no strong UV source in the system. Radio observations showed a point source in the system that might be consistent with weak star formation. This convinced us that we needed an optical spectrum of the system.

Spectra give several crucial pieces of information – first, by measuring redshifts we can determine an accurate distance. This tells us whether all four galaxies genuinely belong to a single interacting group, or whether some appear in projection. Knowing the distance, we can also use the UV and radio flux measurements as diagnostics of the total star formation rate. Finally, with really accurate spectroscopy, we might be able to measure the kinematics of the galaxies, and measure the velocities to get a 3-D picture of how the four members are interacting.

Since Sloan doesn’t have a spectrum of this system, we needed more observations. Danielle Berg, a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, observed the Violin Clef in September using the 6.5-meter Multiple Mirror Telescope in Arizona and obtained two optical spectra.

The analysis has shown that all four galaxies lie at the same redshift (z=0.0956 +- 0.002), and are likely all genuine members of the same group. None of the galaxies show evidence of strong star formation, confirming the red colors that we see in the Sloan data.

The next step in the analysis will be working with simulations like the ones in Merger Zoo. Having confirmed that this really is a quadruple merger will significantly constrain the merger models, and hopefully give us well-defined parameters for the age and history of the system. This is a step that Zooites can help with – if you go to http://mergers.galaxyzoo.org/merger_wars, you can identify simulations that resemble the Violin Clef. We need more clicks at this point, so please consider going to Merger Zoo and helping out! We hope that this will result in another scientific publication soon for the Galaxy Zoo team, and it’s been an exciting project to work on.

– cheers,

Kyle

Radio Peas on astro-ph

Today on astro-ph the Peas radio paper has come out! I discussed the details of the radio observations in July, after the paper had been submitted. The refereeing process can take several months, from the original submission until the paper is accepted.

The paper is very exciting to all of us that worked on the original Peas paper, because it is a great example on how these exciting young galaxies (not too far away) are giving us insights into the way galaxies form and evolve. In the case of the Radio Peas, the observed radio emission suggests that perhaps galaxies start out with very strong magnetic fields.

Galaxy Zoo podcast with S and T

There’s an article on Galaxy Zoo in this month’s Sky and Telescope which comes with a podcast!

Follow the Zooites' Academic Exploits

This post is a plug for two of our forum members – Waveney and Alice – who have been inspired by Galaxy Zoo to go and start a course at university in astronomy. Waveney is working on a Ph.D at the Open University and Alice is doing an MSc course at Queen Mary University. Both are blogging about their experiences on the forum, so if you’re interested in what they are up to, go check out their reports.

The links are:

Citizen Science in Action: the "Violin Clef" merger

Just a few days ago, long-time forum member Bruno posted a curious galaxy as his choice for “Object of the Day” for September 9th. Ahd what a strange merger it is!

(SDSS Skyserver link: http://skyserver.sdss3.org/dr8/en/tools/explore/obj.asp?id=1237678620102688907)

These are some really beautiful tidal tails. They are extremely long and thin and appear curiously poor in terms of star formation (very little blue light from young stars), which is odd since mergers do tend to trigger star formation. There is no spectrum so we do not know the redshift of the object. It is also not clear if the objects at either end are associated or just a projection.

There are photometric redshifts, then the whole system is over 110 kiloparsec across (that’s almost 360,000 light years!) which is big enough to catch even the attention of astronomers.

The “violin clef” merger also has a curious NVSS radio counterpart. What that is all about we don’t know yet – it could be a signal from star formation, or it could be a feeding black hole. The Galaxy Zoo team spent over half an hour discussing this object during a telecon meeting yesterday and we’re all excited.

We still know very little about the system, so if you want to help us figure out what’s going on here, why not head over to the Merger Zoo and simulate the cosmic collision that gave rise to this beautiful and enigmatic object:

Happy galaxy smashing!

Supernova hunters discover a rare beast

The work of the Galaxy Zoo : Supernova hunters recently paid off with the publication of a paper about a rather unusual supernova. Lead author, Kate Maguire – an astronomer at the University of Oxford working on supernovae and in particular exploding stars that can be used to measure the expansion of the Universe – tells us more :

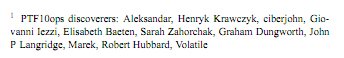

The supernova named ‘PTF10ops’ was discovered by the supernova zoo using images from the Palomar Transient Factory Telescope in California and a report on this interesting SN has now been accepted for publication in the journal, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Thanks to the very rapid discovery of this supernova by members of the supernova zoo, we were able to start taking observations very soon after explosion with many telescopes around the world such as the 4.2 m William Herschel Telescope on the Canary Island of La Palma, the 3 m Shane telescope at the Lick Observatory, California and at one of the two 10 m telescopes located at the Keck Observatory in Hawai’i.

An image of the field of PTF10ops (located at the centre of the crosshairs) taken with the WHT+ACAM on La Palma, Canary Islands. The largest galaxy with spiral arms located in the upper left quadrant is the host galaxy of PTF10ops, located at a distance of 148 kpc from the supernova position. This is the largest separation of any SN Ia discovered to date.

PTF10ops turned out to be a very interesting supernova – a peculiar type Ia supernova. Type Ia supernovae are explosions that occur when a white dwarf (a small, dense star) collapses when it pulls matter from a companion star and grows to have a mass of more than 1.4 times that of the Sun. At this critical mass, a thermonuclear reaction is triggered, that destroys the star in a massive explosion that we call a type Ia supernova. Type Ia supernovae are very important because they are used as cosmological distance indicators and were used in the discovery that the expansion rate of the universe is accelerating.

PTF10ops had unusual observational properties that suggest that maybe a new type of supernova explosion has been discovered. It is located very far from its host galaxy, actually the farthest supernova from the centre of its host galaxy discovered to date. Its spectra also contained signs of rare elements such as Titanium and Chromium. In normal Type Ia supernovae, how long a supernova stays bright is directly related to its peak brightness, but PTF10ops did not follow this rule and stayed brighter for much longer than expected. It is still unclear what it was about the star that exploded that produced this unusual supernova, maybe it was very old star or maybe we are seeing some sort of new, unknown explosion.

In the future, we hope to take images of more objects like this using the Palomar Transient Factory and then with the invaluable help of the supernova zoo members, we can catch these supernovae very soon after explosion and start follow up observations immediately to get images and spectra to better understand these rare supernova explosions.

P.S. Here’s the piece of the paper crediting the discoverers – well done all!