RGZ Team Spotlight: Stas Shabala

To introduce you to the Radio Galaxy Zoo team, we’re doing a series of blog posts written by each team member — in no particular order. Meet Stas Shabala, our team Project Manager from the University of Tasmania, Australia:

I grew up in Tasmania, a gorgeous part of the world which also happens to be the place Grote Reber, the world’s first radio astronomer, called home for 50 years. After finishing university, I made a pilgrimage that these days is more or less standard for young Australians – I moved to the UK. I ended up staying for six years, and it was during my time in Oxford that I became involved with Galaxy Zoo. Normal galaxies are interesting but – given our history- a Tasmanian’s true heart will always be with radio astronomy. That’s why I have such a soft spot for Radio Galaxy Zoo.

Recently, I’ve been trying to figure out why radio galaxies come in so many different shapes, sizes and luminosities. Data from Radio Galaxy Zoo will go a long way to answering these questions. I’ve also had lots of fun using active black holes as beacons to accurately measure positions on Earth. It’s just like navigation by stars, but much more precise because stars move around in the sky a fair bit, whereas black holes don’t. The neat thing is, these measurements make it possible to study all sorts of geophysical processes here on Earth. It’s such a cool concept- using black holes to measure the movement of tectonic plates!

More Information on Tailed Radio Galaxies (Part 2)

This is the second half of a detailed description of tailed radio galaxies from RGZ science team member Heinz Andernach. If you haven’t yet read the first part, it’s here: please feel free to leave any questions in the comments section.

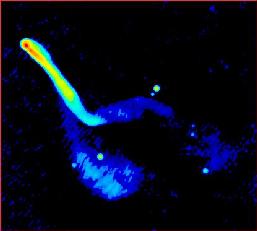

Apart from distance or angular resolution, another reason for causing a NAT may be projection of the inner jets along the line of sight, as seems to be the case for NGC 7385 (PKS 2247+11). In the low-resolution image above, the inner jets are not resolved, but the corresponding far outer tails start to separate widely about half-way down their length. At much higher resolution:

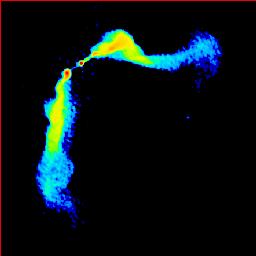

the two opposite jets can be clearly seen to emanate from the very core, the central point-like source in this contour plot. However, the jet heading north-east (upper left) has been bent and diluted by almost 180° such that it runs behind the other jet for about 200 kpc (about 650,000 light-years) before the two jets separate and can be distinguished again in the lower-resolution image. The combination of these images is also a good example showing that different interferometers (large and small) are needed to show all features of a complex radio source.

However, not all apparently tailed radio sources would show their double jets near the core at high resolution. One curious example is IC 310, among the first “head-tails” to be discovered, has stubbornly resisted to show double jets, and is now accepted as a genuinely one-sided jet of the type that BL Lac objects, implying that its jet points fairly close to our line of sight.

An atlas of the radio morphologies in general of the strongest sources in the sky can be found here. Several NATs and WATs can be distinguished on the collection of icons. However, this atlas only comprises the 85 strongest sources in the sky. The enormous variety of bent radio galaxies present in the FIRST radio survey was explored with automated algorithms by Proctor in 2011, who tabulated almost 94,000 groups of FIRST sources attaching to them a probability of being genuine radio galaxies of various morphological types. The large variety of bent sources can be seen e.g. in her Figures 4, 7 and 8. However, this author made no attempt to find the host galaxies of these sources. Users of Radio Galaxy Zoo will eventually come across all these sources and tell us what the most likely host galaxy is.

Distant clusters of galaxies, important for cosmological studies, tend to get “drowned” in a large number of foreground galaxies present in their directions, so they are difficult to be distinguished on optical images. One way to find such clusters is by means of their X-ray emission, but since X-rays can only be detected from Earth-orbiting telescopes like ROSAT, ASCA, XMM-Newton, Chandra and Suzaku (to name only a few), this is a rather expensive way of detecting them. A “cheaper” way of looking for distant clusters is to use NATS and WATs as “beacons”. In fact, authors like Blanton et al. (2001) have followed up the regions of tailed radio sources and see the variety of morphologies:

Note that several of these WATs appear like twin NATs, but actually they are a single WAT, being “radio quiet” at the location of their host galaxies (not shown in the image above), but their jets “flare up” in two “hot spots” on opposite sides of the galaxy where they suddenly bend. The authors confirmed the existence of distant clusters around many of them. So, whenever RGZ users identify such tailed radio galaxies, we know that with a high probability we are looking in the direction of a cluster of galaxies.

An excellent introduction (even though 34 years old!) to radio galaxy morphologies and physics is the article by Miley 1980 (or from this alternate site). This author already put together a few well-known radio sources into what he called a “bending sequence”:

Tailed Radio Galaxies: Cometary-Shaped Radio Sources in Clusters of Galaxies (Part 1)

Today’s post is written by Heinz Andernach (Univ. of Guanajuato, Mexico), a member of the Radio Galaxy Zoo science team and an expert on radio galaxies. This is the first half of a detailed science post explaining what we know — and what we don’t know — about tailed radio galaxies, along with how Radio Galaxy Zoo volunteers are helping us understand them. There’s a lot of information here, so if you have questions please ask them in the comments.

In 1968, Ryle and Windram found the first examples of a type of radio galaxies, whose radio emission extends from the optical galaxy in one direction in the form of a radio “tail” or “trail”. These examples were NGC 1265 and IC 310 in the Perseus cluster. Soon other examples were found in the Coma cluster of galaxies (NGC 4869, alias 5C4.81), as well as the radio galaxy 3C 129. The latter lies right in the plane of our Galaxy, and its membership in a cluster of galaxies was only confirmed much later, hampered by the dust obscuration of our own Milky Way. All three of these tailed radio galaxy were located close to another radio source, with their tails pointing more or less away from their radio neighbor, leading these authors to suspect that the tails were blown by winds of relativistic particles ejected from the radio neighbor. Soon thereafter higher-resolution observations of these sources revealed that the host galaxies showed the same two opposite radio jets as known from other, less bent, radio galaxies like Cygnus A, but close to the outskirts of the optical galaxies the jets would both bend in some direction, thought to be the direction opposite to the motion of the host galaxy through the so-called “intergalactic” or “intracluster” medium, which had been discovered from X-ray observations at about the same time. Later on, doubts were cast on this scenario, as it was found that the optical hosts of tailed radio galaxies in clusters did not move about within their clusters with high enough velocities to explain the bends in the jet.

A detailed study of the prototypical WAT source 3C 465 (image above) at the center of the rich Abell cluster of galaxies A2634 by these authors did not result in any plausible explanation for the bending of their radio trails. Later on, with more detailed X-ray images of clusters of galaxies, it was found that tailed radio galaxies occur preferentially in high-density regions of the intracluster medium (i.e. where the X-ray intensity is high; for more information, see this 1994 study) and even cluster mergers were made responsible for the formation of radio tails in this 1998 study. More recently authors seem to converge on the compromise idea that the combination of high ambient density and modest speeds of the host galaxy with respect to the ambient medium are able to produce the bends, but in this blog I would rather like to concentrate on the variety of morphologies shown by these objects in order to help RGZ users to classify them.

Above all, the term “tailed radio galaxies” should never be separated from the word “radio”. Some authors talk about “tailed” or “head-tail (HT) galaxies”, but the tail always occurs in their radio emission, usually far beyond the optical extent of their host galaxies. So, let us reserve the term “head-tail galaxies” for a future when optical tails may be detected in certain galaxies. Also, please note that while galaxies sometimes show optical tails due to tidal interactions, these are of totally different origin than the radio tails we discuss here.

Arp 188, a.k.a. The Tadpole Galaxy: not a tailed radio galaxy. I repeat, not the subject of this blog post.

Tailed radio galaxies are often subdivided into wide-angle (WAT) and narrow-angle tailed (NAT) radio galaxies, referring to the opening angle between the two opposite jets emanating from the nucleus of the optical galaxy, where we expect the supermassive black hole doing its job of spewing out the jets. However, the distinction between WATs and NATs depends strongly on the angular resolution and/or the distance to the radio source. E.g., the first HT radio galaxy to be discovered (NGC 1265; images below) may be called a WAT at high resolution, but appears as a (much larger) NAT at lower resolution, shown by this sequence of high, medium and low resolution radio images:

Radio Galaxy Zoo: a close-up look at one example galaxy

We hope everyone’s been excited about the first few days of Radio Galaxy Zoo; the science and development teams certainly have been. As part of involving you, the volunteers, with the project, I wanted to take the opportunity to examine and discuss just one of the RGZ images in detail. It’s a good way to highlight what we already know about these objects, and the science that your classifications help make possible.

For an example, I’ve chosen the trusty tutorial image, which almost everyone will have seen on their first time using RGZ. We’ll be focusing on the largest components in the center (and skipping over the little one in the bottom left for now).

The data in this image comes from two separate telescopes. Let’s look at them individually.

The red and white emission in the background is the infrared image; this comes from Spitzer, an orbiting space telescope from NASA launched in 2003 (and still operating today). The data here used its IRAC camera at its shortest wavelength, which is 3.6 micrometers. As you can see, the image is filled with sources; the round, smallest objects are either stars or galaxies not big enough to be resolved by the telescope. Larger sources, where you can see an extended shape, are usually either big galaxies or star/galaxy overlaps that lie very close together in the sky.

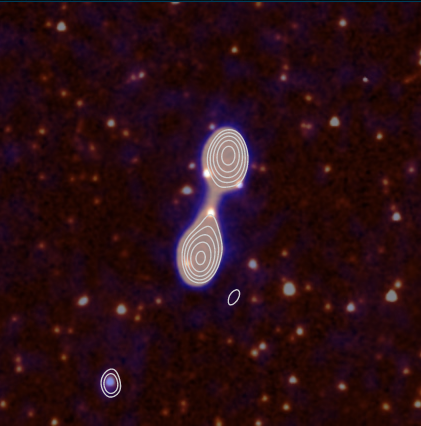

Overlaid on top of that is the data from the radio telescope; this shows up in the faint blue and white colors, as well as the contour lines that encircle the brightest radio components. The telescope used is the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA) in rural New South Wales, Australia. This data was taken as part of the ATLAS survey, which mapped two deep fields of the sky (named ELAIS S1 and CDF-S) in the radio at a wavelength of 20 cm.

So, what do we know about the central sources? From their shape, this looks like what we would call a classic “double lobe” source. There are two radio blobs of similar size, shape, and brightness; almost exactly halfway between them is a bright infrared source. Given its position, it’s a very good candidate as a host galaxy, poised to emit the opposite-facing jets seen in the radio.

This object doesn’t have much of a mention in the published astronomical literature so far. Its formal name in the NASA database is SWIRE4 J003720.35-440735.5 — the name tells us that it was detected as part of the SWIRE survey using Spitzer, and the long string of numbers can be broken up to give us its position on the sky. This is a Southern Hemisphere object, lying in the constellation Phoenix (if anyone’s curious).

The only analysis of this galaxy so far appeared in a paper published by RGZ science team member Enno Middelberg and his collaborators in 2008. They made the first detections of the radio emission from the object, and matched the radio emission to the central infrared source by using an automatic algorithm plus individual verification by the authors. They classified it as a likely AGN based on the shape of the radio lobes, inferring that this meant a jet. It’s also one of the brighter galaxies that they detected in the survey, as you can see below – brighter galaxies are to the right of the arrow. That might mean that it’s a particularly powerful galaxy, but we don’t know that for sure (for reasons I’ll get back to in a bit).

So what we know is somewhat limited – this object has only ever been detected in the radio and near-infrared, and each of those only have two data points. The galaxy is detected at both at 3 and 4 micrometers in the infrared, but the camera didn’t detect it using any of its longer-wavelength channels. This makes it difficult to characterize the emission from the host galaxy; we need more measurements at additional wavelength to determine whether the light we see (in the non radio) is from stars, from dust, or from what we call “non-thermal processes”, driven by black holes and supernovae.

One of the biggest barriers to knowledge, though, is that the galaxy doesn’t currently have a measured distance. Distances are so, so important in astronomy – we spend a massive amount of time trying to accurately figure out how far away things are from the Earth. Knowing the distance tells us what the true brightness of the galaxy is (whether it’s a faint object nearby or a very bright one far away), what the true physical size of the radio jets are, at what age in the Universe it likely formed; a huge amount of science depends critically on this.

Usually distances to galaxies are obtained by taking a spectrum of it with a telescope and then measuring the Doppler shift (redshift) of the lines we detect, caused by the expanding Universe. The obstacle is that spectra are more difficult and more expensive to obtain than images; we can’t do all-sky surveys in the same way we can with just images. This is one reason why these cross-identifications are important; if you can help firmly identify the host galaxy, we can effectively plan future observations on the sources that need it.