Meeting the Astronomy World

This guest post is from Anna Han, an undergrad working on the Hubble data from Galaxy Zoo:

I attended the AAS Conference in Austin, Texas with the Yale Astronomy and Physics Department to present the results from my research last summer. Many thanks to everyone in the department and Galaxy Zoo who gave me this opportunity and continue to support me through my work. It is because of their guidance that I was able to present a research poster at the conference this winter and enjoy a whole new experience.

The AAS Conference was fascinating, motivating, and overwhelming all at the same time. Starting from 9:00am every morning, I listened to various compact 10-minute talks given by various PhD candidates, post-docs, and researchers from around the world. Though I must admit some of the ideas presented went over my head, I learned more and more with each talk I heard.

The midday lunch breaks made up one of my favorite parts of the conference. Yes, the ribs in Texas are good. But no amount of delicious southern cuisine compares to how welcome and at ease I felt with fellow astronomers kind enough to invite me, a newbie sophomore undergraduate, to lunch. Lunch became my 2-hour my opportunity to talk one-on-one with other researchers and get informed on their work. When my questions ran out, I gladly took the chance to introduce my own research and use their feedback to better prepare for my poster presentation.

On Thursday morning, I tacked up my poster in the exhibit hall and stood guard, armed with organized details of my research and cookies as bait. Let me confess now that I have never been at or in a science fair, but I imagine it must be similar to what I experienced that day. Non-scientist citizens and experts in AGN alike perused my poster and asked questions. Every once in a while I recognized a familiar face: members from my research group, students I had befriended throughout the conference, and fellow researchers I had shared lunch with stopped by to see my poster. Explaining my research to someone who was interested (either in my work or the cookies) was an immensely rewarding experience. I felt proud of what I had accomplished and so thankful to the people who helped me do it. The encounters with other people also gave me ideas for future directions I could proceed in.

This semester, I plan to continue searching for multiple AGN signatures in grism spectra of clumpy galaxies. My experience at the AAS Conference has inspired me to develop a more systematic search for clumpy galaxies using Galaxy Zoo and explore in more detail the possibility of low redshift galaxies containing multiple AGN. To the citizens of Galaxy Zoo, thank you again, and I hope for your continued support!

Post-starburst galaxies paper accepted!

Great news everybody!

The post-starburst galaxies paper has now been accepted by MNRAS. You can find the full paper for download on astro-ph.

The Science Behind Classifying Simulated AGN

Hello Zooites,

This is a dual-purpose post: first, to introduce myself. My name is Brooke Simmons. I’m a graduate student in the final year of my PhD at Yale, and my scientific focus is on examining the co-evolution of supermassive black holes (SMBHs) and their host galaxies. My specialization is in the morphology of galaxies hosting active SMBHs, so naturally I’ve been very intrigued by the Galaxy Zoo project ever since it started. And I’m very impressed by the work that you all do. So when Chris and Carie asked me about simulating some AGN as part of the Galaxy Zoo project, I jumped at the chance. I have pretty extensive experience simulating AGN and host galaxies — more on that in a moment — and I was very excited to have the opportunity to extend that kind of science into the realm of Galaxy Zoo.

I heard later that there were some issues regarding the simulations, and that’s the other purpose of this post. I’d like to try and explain the reasons I think the simulations are important to the science being done in the Zooniverse, and clarify some of the details, if possible. I’m quite new here and I realize that there are many levels of experience reflected in the Zooite population, from newcomers to the field to those who are experienced at following up on objects of interest and searching the scientific literature. So I hope, in giving this science background, that those of you who have heard it before will bear with me, and those of you who haven’t (or, well, anyone really) will feel free to ask any questions that might come up.

In the field of galaxy evolution, it’s now clear there is some sort of mechanism that affects both the evolution of galaxies and the growth of their central black holes together, but we don’t really understand what it is (or what they are) — yet. In terms of scale, it’s rather incredible that they are connected at all. We may call them supermassive black holes, but they’re generally a small percentage of the total galaxy mass, and they’re absolutely tiny when compared to the size of the galaxy. I like to describe it in terms of a football match: the packed, somewhat chaotic crowd in the stands shouldn’t know or care what the ant right in the middle of the playing field is doing. Nor should the ant particularly be aware of how the cheering crowd is shifting and reacting. Yet it is well established that the crowd (the stars in the galaxy) and the ant (the central black hole) somehow know about each other.

How does this work? What forces (or combination of phenomena) act to influence both the single, massive point at the center of a galaxy and the billions of stars around it? Is it a one-sided influence, or is it a feedback mechanism that ends up causing them both to evolve in sync? The co-evolution of galaxies and black holes is one of the fundamental topics of galaxy evolution, and many questions remain unanswered. In order to try to answer these questions, we observe both central black holes and the galaxies that host them, at a variety of redshifts/lookback times, so that we can see how these two things evolve.

However, for all but very local galaxies, it’s very difficult to see a signal from a galaxy’s central SMBH amid all the stellar light from the galaxy. So, we turn to that subset of SMBHs that are actively accreting matter, which in turn heats up and discharges enormous amounts of energy as it falls into the gravitational potential of the black hole. Those, which we call active galactic nuclei (AGN), we can see much more easily, and out to very high redshift. They radiate across the whole of the electromagnetic spectrum, from radio to gamma rays. At optical wavelengths they are sometimes buried in dust and gas, which obscures their light and means they look identical to so-called “inactive” galaxies. But in other cases, the AGN are unobscured or only partially obscured, and then they are extremely bright — so much so that they can far outshine the rest of the galaxy.

So, looking at the central SMBHs of inactive galaxies is impossible for very distant galaxies, because the host galaxy swamps the dim signatures of the black hole. But looking at the hosts of active black holes (AGN) can be difficult too, because the AGN signal can swamp the host galaxy. It’s not impossible to disentangle the two in order to examine the host galaxy separately from the AGN, but it adds a level of complexity to the process. Morphological fitting programs executed by a computer do a reasonable job, but actually — as you all know — the human brain is excellent at this kind of pattern recognition. You all can clearly tell the difference between a host galaxy and its central AGN, to the point where many of you have been following up your classified objects and identifying spectral features of AGN. That is so impressive!

In fact, what you collectively do is new and different and in many ways a significant improvement over “parametric” methods that use automated computer codes to fit galaxy morphology models to images. Those have their uses, too, of course, but you all pick up nuances that parametric methods simply miss. And part of what that means is that the data we have on how the presence of an AGN (bright or faint) affects morphological classification may or may not apply to your work. Within the automatic fitting programs, there are subtle effects that can occur. For example, a small galaxy bulge may look the same to a parametric fitting routine as a central AGN, with the consequence that it may think it has found one when in fact it’s the other. Or, when both a small bulge and a central AGN are present, a computer code to fit the morphology might be more uncertain about how much luminosity goes with each component. I know all this because it has now been studied for automated/parametric morphology fitting codes:

- Sànchez et al. (2004) is mainly a data analysis paper on AGN host galaxies, but contains a subsection on simulations;

- Simmons & Urry (2008) is a paper describing two sets of AGN host simulations that combine for over 50,000 simulated galaxies (yes, that Simmons is me);

- Gabor et al. (2009) is another data analysis paper that contains AGN host simulations; and

- Pierce et al. (2010) is a dedicated simulations paper with a smaller sample than Simmons & Urry, but which also extends the analysis to host galaxy colors.

All of this analysis was undertaken with Hubble data, much like the images of simulated AGN that have been incorporated into Galaxy Zoo. These are small effects that only impact a fraction of classifications, but the simulations are crucial because they both let us know the limits of our classification methods and, just as importantly, enable us to quantify precisely how confident we are that the classifications are accurate. The parametric methods are very accurate, but it is absolutely essential that we find out just how the presence of an AGN affects classification in this setting, which is of course quite different.

It’s always exciting for a scientist to say “I don’t know the answer, but I know how we can find out.” And in this case, that means extending the simulations that we have done to the case of visual classification. There are a few ways to simulate AGN, but the key process is to create a situation where the analysis takes place on a known quantity so that you can compare what you know to what the analysis finds. In this case (which is similar in method to the first set of simulations in Simmons & Urry), that means:

- Start with a set of galaxies for which we know the initial “answer,” i.e., the morphology;

- Add a simulated signal from a central SMBH, using a wide range of luminosity ratios between galaxy and SMBH, and a range of AGN colors;

- Repeat the classification process in exactly the same way as for the initial set of galaxies, to see if the answers change.

Now, it may be that the answers change in some subtle way, as they do when the morphological analysis is done by a computer. If that’s the case, then the analysis quantifies that effect so that we can understand it and account for it. Or, it may be that you see right through it — and if so, that’s great! If you look at a galaxy with an AGN and say, “of course I can tell that that galaxy has an AGN in it, and I can still classify the galaxy in the same way,” fantastic. It potentially means you all are doing better science than a traditional parametric analysis in yet another way. Either way, the answer is very useful.

I know this post is already quite long, but I think it’s important to make one other point about the simulations. When you’re simulating something like this to understand the effects of a new feature on analysis you think you understand very well, it’s very important to try to push the limits of that analysis. In this case, that means simulating AGN that are both so faint that there’s pretty much no way you could possibly see them in their host galaxies, and so bright that they will be blindingly obvious to anyone paying attention.

And you all are most definitely paying attention. In reading comments on other blog posts, I saw that some Zooites were displeased with the way the very brightest simulated AGN looked strange, and even artificial. And I know there were some communication issues regarding the release of the simulations; for that I apologize. Actually, though, knowing which objects you found odd is a part of the science, too. Simulations like this can be used not only to understand the science of determining galaxy morphology, but also to understand the science of separating the AGN itself for later analysis — as I said earlier, both are needed to understand the co-evolution of black holes and galaxies. So questions like, “when does the AGN get lost in the galaxy?” and “when does the AGN totally overtake the galaxy?” are vital. It is also definitely the case that we were pushing the limits of not just the classification, but also of the software that is used to make the simulated AGN. That’s why the very brightest of them look a bit… weird. I do think the science is still possible even if it’s clear that it’s a simulation on first glance, and I really appreciate your patience with both me and the software on that issue.

By the way, I have a feeling you all are going to turn out to be considerably better at classifying galaxies with AGN in them than the computer is, but of course that’s just my hypothesis — it’s important to actually go through the process of classifying simulated galaxies. That way, when someone comes up to us and says, but how do you know all these citizen scientists are really that accurate? AGN can have a subtle effect on the fitted morphologies of galaxies, after all, we can say, “but we do know they’re that accurate — and here’s how we know.”

Thanks all for reading — if you got this far, that probably deserves an award in itself — and please feel free to ask any questions you might have. If you have a concern that you feel I didn’t address, please let me know that as well. I would very much appreciate your input!

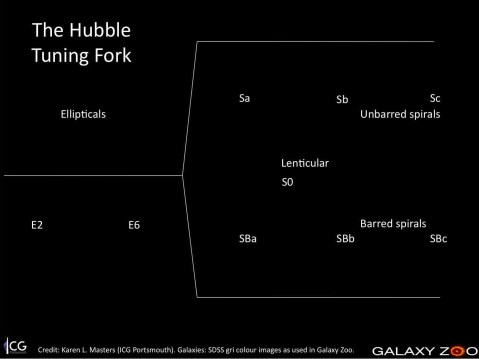

The Hubble Tuning Fork

The gold standard for galaxy classification among professional astronomers is of course the Hubble classification. With a few minor modifications, this classification has stood in place for almost 90 years. A description of the scheme which Hubble calls “a detailed formulation of a preliminary classification presented in an earlier paper” (an observatory circular published in 1922) can be found in his 1926 paper “Extragalactic Nebulae” which is pretty fun to have a look at.

Hubble’s classification is often depicted in a diagram – something which is probably familiar to everyone who has taken an introductory astronomy course. Astronomers call this diagram the “Hubble Tuning Fork”. I have been meaning for a while to make a new version of the Hubble tuning fork based on the type of images which were used in Galaxy Zoo 1 and 2 (OK the prettiest ones I could find – these are not typical at all). Anyway here it is. The Hubble Tuning Fork as seen in colour by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey:

I should say that my choice of galaxies for the sequence owes a lot of credit to an excellent Figure illustrating galaxy morphologies in colour SDSS images which can be found in this article on Galaxy Morphology (arXiV link) written by Ron Buta from Alabama (Figure 48). I strongly recommend that article if you’re looking for a thorough history of galaxy morphology.

Inspired by the “Create a Hubble Tuning Fork Diagram” activity provided by the Las Cumbres Observatory, I also provide below a blank version which you can fill in with your favourite Galaxy Zoo galaxies should you want to. I have to say though, the Las Cumbres version of the activity looks even more fun as they also talk you through how to make your own colour images of the galaxies to put on the diagram.

Anyway I hope you like my new version of the diagram as much as I do. Thanks for reading, Karen.

What is a Galaxy?

What is a Galaxy?

“Any of the numerous large groups of stars and other matter that exist in space as independent systems.” (OED)

“A galaxy is a massive, gravitationally bound system that consists of stars and stellar remnants, an interstellar medium of gas and dust, and an important but poorly understood component tentatively dubbed dark matter.” (Wikipedia)

“I’ll know one when I see one” (Prof. Simon White, Unveiling the Mass of Galaxies, Canada, June 2009)

The question of “What is a galaxy” is being debated online at the moment, after it was posed by two astronomers – Duncan Forbes and Pavel Kroup in a paper posted on the arXiv last week. It’s an article written for professional astronomers, so doesn’t shirk the technical language in the suggestions for definitions, but in a very “zoo like” fashion (and following the model of the IAU vote on the definition of a planet which took place in 2006) invites the readers of the paper to vote on the definition of a galaxy. This has been reported in a few places (for example Science, New Scientist) and everyone is invited to get involved in the debate.

In fact Galaxy Zoo is cited in the press release about the work as one of the inspirations to bring this debate to a vote.

So what’s all the fuss about? Well it all started because of some very tiny galaxies which have been found in the last few years. There has been a debate raging in the scientific literature over whether or not they differ from star clusters, and where the line between large star clusters and small galaxies should be drawn. It used to be there was quite a separation between the properties of globular clusters (which are spherical collections of stars found orbiting galaxies – the Milky Way has a collection of about 150-160 of them) and the smallest known galaxies.

The globular cluster Omega Centauri. Credit: ESO

For example globular clusters all have sizes of a few parsecs (remember 1 parsec is about 3 light years), and the smallest known galaxies used to all have sizes of 100pc or larger. Then these things called ‘ultra compact dwarfs’ were found (in 1999), which as you might guess are dwarf galaxies which are very compact. They have sizes in the 10s of parsec range, getting pretty close to globular cluster scales.

UCDs in the Fornax Cluster. The background image was taken by Dr Michael Hilker of the University of Bonn using the 2.5-metre Du Pont telescope, part of the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile. The two boxes show close-ups of two UCD galaxies in the Hilker image. (Credit: These images were made using the Hubble Space Telescope by a team led by Professor Michael Drinkwater of the University of Queensland.)

Such objects begin to blur the line between star clusters and galaxies.

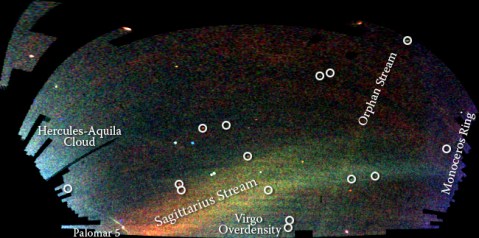

And there are things which have been called ‘ultra-faint dwarf spheroidal (dSph) galaxies’. These look nothing like the kind of galaxies you’re used to in SDSS images, although they were found in SDSS data – but perhaps not how you might expect. Researchers colour coded the stars in SDSS by their distance, and looked for overdensities or clumps of stars. So far several concentrations of stars at the same distance have been found. Some were new star clusters, but some look a bit like galaxies. If these are galaxies they are the smallest know, with only 100s of stars. Some are so faint that they would be outshone by a single massive bright star.

A map of stars in the outer regions of the Milky Way Galaxy, derived from the SDSS images of the northern sky, shown in a Mercator-like projection. The color indicates the distance of the stars, while the intensity indicates the density of stars on the sky. Structures visible in this map include streams of stars torn from the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy, a smaller 'orphan' stream crossing the Sagittarius streams, the 'Monoceros Ring' that encircles the Milky Way disk, trails of stars being stripped from the globular cluster Palomar 5, and excesses of stars found towards the constellations Virgo and Hercules. Circles enclose new Milky Way companions discovered by the SDSS; two of these are faint globular star clusters, while the others are faint dwarf galaxies. Credit: V. Belokurov and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

The paper suggests as a minimum that a galaxy ought to be gravitationally bound, and contain stars. They point out that this definition includes star clusters as well as all galaxies, so suggest some additional criteria might be needed. They make a list of suggestions, which we are invited to vote on. For full details (and if you are technically minded) I refer you to the paper. It’s a lesson in gravitational physics in itself (although as I said it is aimed at professional astronomers). Here is my potted summary of the suggestions they make:

1. Relaxation time is longer than the age of the universe. Basically this means that the system ought to be in a state where the velocity of a star in orbit in it will not change due to the gravitational perturbations from the other stars in a “Hubble time” (astronomer speak for a time roughly as long as the age of the universe). This will exclude star clusters which are compact enough to have shorter relaxation times, but makes UCDs and faint dSph be galaxies.

2. Size > 100 pc (300 light years). Pretty self explanatory. Sets a minimum limit on the size. This makes the UCDs not be galaxies.

3. Should have stars of different ages. (a “complex stellar population”). The stars in most star clusters are observed to have formed all in one go from one massive cloud of gas. But in more massive systems not all the gas can be turned into stars at one time, so the star formation is more spread out resulting in stars of different ages being present. However there are some (massive) globular clusters which are know to have stars of different ages, so they would become galaxies in this definition.

4. Has dark matter. Globular clusters show no evidence for dark matter (ie. their measured mass from watching how the stars move is the same as the mass estimated by counting stars), while all massive galaxies have clear evidence for dark matter. The problem here is that this is a tricky measurement to make for UCDs and many dSph, so will leave a lot of question marks, and may not be the most practical definition.

5. Hosts satellites. This suggests that all galaxies should have satellite systems. In the case of massive galaxies these are dwarf galaxies (for example the Magellanic clouds around the Milky Way), and many dwarf galaxies have globular clusters in them. But there are some dwarf galaxies with no known globular clusters, and UCDs and dSph do not have any.

The paper finished by describing some of the most uncertain objects and provides the below table to show which would be a galaxy under a given definition. I’ve tried to explain what some of these all are along the way, and here is a short summary:

Omega Cen (first image above) is traditionally thought to be a globular cluster (ie. not a galaxy). Segue 1 is one of the ultra faint dSphs found by counting stars in SDSS images (3rd image). Coma Berenices is a bit brighter than a typical ultra faint dSph, and a bit bigger than a typical UCD. VUCD7 is (the 7th) UCD in the Virgo cluster (not the most imaginative name there!), so simular to the Fornax cluster UCDs shown in the second image. M59cO is a big UCD – almost a normal dwarf galaxy but not quite. BooII (short for Bootes III) and VCC2062 are objects which may possibly be material which has been tidally stripped off another galaxy. Or they might be galaxies.

Anyway if you’re interested you can join in the debate here. And if you read the paper you can vote. I voted, but I think in the interest of letting you make up your own mind I’m not going to tell you what my decision was.

Oh and I just started a forum topic on it in case you want to debate inside the Zoo before voting.

First X-ray Data of the Mergers with Chandra

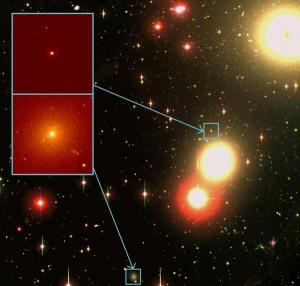

I just got notice from the people at the Chandra Science Center that Chandra has executed the observation of the first Galaxy Zoo merger – part of our study to understand black holes in mergers. This is the first of twelve such observations that should take place over the next year or so. The main science question we have that this program will help us answer is: in how many mergers do both black holes feed?

All I have at the moment are the quick-look data that that they sent me. They are more or less raw images. Here is the full frame:

And here is a zoom-in:

This is raw data, rather than properly analyzed data, so we can’t really draw any firm conclusions based on it yet, but it seems like there is no significant source detected. What does that mean? Assuming that there really is no source after we properly analyze the data, then the black hole(s) in this particular merger are either not feeding very much, or they are hidden behind lots of gas and dust.

For now, we will wait for the actual data to fully analyze it, and for the remaining 11 targets to be observed.

An Extra-galactic Halloween

At a pumpkin carving event yesterday, we (a group of people from Yale astro) tried to come up with an appropriate theme for our pumpkin. Naturally, we decided on the Hubble Sequence of galaxy morphology:

Elliptical

Lenticular

Early Spiral

Late Spiral

Irregular

And the artists…

Galaxies spiralling out of control

Today’s OOTW features Alice’s OOTD, posted on the 29th of July.

AHZ40004wr from Hubble Zoo

This is AHZ40004wr, a galaxy residing in the constellation Taurus around 3 billion light years away. It’s a wonderful spiral galaxy, and following its spiral arms is a large dust lane, a place full of young stars and stars that are only just being formed.

AHZ40004wr by Swengineer

Zooite Swengineer gave us a wider view of AHZ40004wr and the surrounding galaxies by working with the FITS images and revealed the mess of galaxies above. The main spiral galaxy in the background is 2MASS J03324999-2734330, an X-ray source according to SIMBAD, and it is also around 3 billion light years away.

You can view more images of these galaxies here and here, and to work with the FITS files I recommend DS9 or Aladin, which I used to find the other galaxies details.

And to highlight a request from Alice’s OOTD, Alice would very much like to know if anyone could write any FITS and image editing tutorials on the galaxy zoo forum.

The Sunflower of Canes Venatici

This galaxy is featured in LizPeter’s OOTD for 24th of July 2010.

M63 from the SDSS

This is Messier 63, though I much prefer its other name, the sunflower galaxy. It’s a wonderful dusty spiral galaxy lying 22.9 million light years away from Earth in the constellation Canes Venatici. It’s one of 7 galaxies bound gravitationally together in the M51 group, and according to Wikipedia, it is one of the first objects to be seen to have spiral arms. This was pointed out in 1845 by William Parsons in a time when these objects were thought to be ‘spiral nebulae’ in our own galaxy, and not galaxies themselves. SIMBAD also claims that there is a cluster of stars lying in the foreground of the galaxy.

There are some brilliant Hubble Legacy images and spectra here, and some more from assorted observatories here!