Radio Peas on astro-ph

Today on astro-ph the Peas radio paper has come out! I discussed the details of the radio observations in July, after the paper had been submitted. The refereeing process can take several months, from the original submission until the paper is accepted.

The paper is very exciting to all of us that worked on the original Peas paper, because it is a great example on how these exciting young galaxies (not too far away) are giving us insights into the way galaxies form and evolve. In the case of the Radio Peas, the observed radio emission suggests that perhaps galaxies start out with very strong magnetic fields.

Galaxy Zoo podcast with S and T

There’s an article on Galaxy Zoo in this month’s Sky and Telescope which comes with a podcast!

Follow the Zooites' Academic Exploits

This post is a plug for two of our forum members – Waveney and Alice – who have been inspired by Galaxy Zoo to go and start a course at university in astronomy. Waveney is working on a Ph.D at the Open University and Alice is doing an MSc course at Queen Mary University. Both are blogging about their experiences on the forum, so if you’re interested in what they are up to, go check out their reports.

The links are:

Citizen Science in Action: the "Violin Clef" merger

Just a few days ago, long-time forum member Bruno posted a curious galaxy as his choice for “Object of the Day” for September 9th. Ahd what a strange merger it is!

(SDSS Skyserver link: http://skyserver.sdss3.org/dr8/en/tools/explore/obj.asp?id=1237678620102688907)

These are some really beautiful tidal tails. They are extremely long and thin and appear curiously poor in terms of star formation (very little blue light from young stars), which is odd since mergers do tend to trigger star formation. There is no spectrum so we do not know the redshift of the object. It is also not clear if the objects at either end are associated or just a projection.

There are photometric redshifts, then the whole system is over 110 kiloparsec across (that’s almost 360,000 light years!) which is big enough to catch even the attention of astronomers.

The “violin clef” merger also has a curious NVSS radio counterpart. What that is all about we don’t know yet – it could be a signal from star formation, or it could be a feeding black hole. The Galaxy Zoo team spent over half an hour discussing this object during a telecon meeting yesterday and we’re all excited.

We still know very little about the system, so if you want to help us figure out what’s going on here, why not head over to the Merger Zoo and simulate the cosmic collision that gave rise to this beautiful and enigmatic object:

Happy galaxy smashing!

A Summer Spent Finding Our Galactic Twin

Today’s post is a guest post by A-level Student, Tim Buckman from Portsmouth Grammer School, who spent 6 weeks working with me at Portsmouth University this summer through the Nuffield Science Bursery Scheme.

Finding Our Galactic Twin

For millions of years humans have attempted to understand their place in the cosmos.

We went from the flat Earth to the globe; from a geocentric to a heliocentric solar system, and now we understand we live in the outskirts of a spiral galaxy – a massive collection of stars.

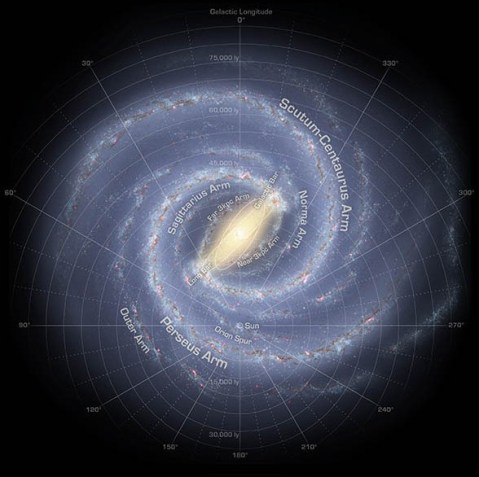

For years though astronomers have endeavoured to find out what The Milky Way, our home galaxy, actually looks like in detail. The difficulty lies in the fact that we live within it, and it would take thousands of years of travel to get a good photo opportunity. The best models suggest that our galaxy is a spiral galaxy with between two and four spiral arms, a central bulge and a bar at the centre. Using what data we have, artists have tried to create an impression of our galaxy’s structure and form, the best guess being the one below.

Recently, the European Southern Observatory released an image of a galaxy which they called as a twin for our own. On the face of it the galaxy (below) looks just like our own, it has a similar number of spiral arms, it has a central bulge and, if you look closely, even a small bar at the centre. It’s name is NGC 6744 and from July of this year, it became our Galaxy’s twin. There is a small problem with this galaxy however, or should I say, a large problem; this galaxy is actually twice the size of our own in mass and size and therefore is a bit of a stretch to suggest it as a copy. We are again stumbling in the dark to find more about where we live.

This is where the Galaxy Zoo project CAN help. It aims with the help of ALMOST 450,000 volunteers, to classify as many galaxies as possible from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. By using this information, we can start to narrow down a list of galaxies to look at. By filtering out those which were seen to have features and were relatively face-on to the camera, we end up with a list of around 17,500 galaxies in total. Again by filtering out those galaxies with the same mass, number of spiral arms and having a bar like the Milky Way, we find that there are just 9 galaxies which fit this criteria. Of these nine galaxies, the one which looked the most like the artists impression was the one shown below. This galaxy, captured through the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) camera is the most likely of the galaxies we have seen to be a clone of our own.

The fact remains that this might, possibly, not be the best Milky Way ‘clone’ in the universe, there are countless galaxies yet to be photographed and there are thousands of galaxies which, due to their orientation, make it very difficult to see whether they are anything like ours. However, with rapid advances in technology, this dream of finding the shape of our galaxy is just around the corner.

Supernova hunters discover a rare beast

The work of the Galaxy Zoo : Supernova hunters recently paid off with the publication of a paper about a rather unusual supernova. Lead author, Kate Maguire – an astronomer at the University of Oxford working on supernovae and in particular exploding stars that can be used to measure the expansion of the Universe – tells us more :

The supernova named ‘PTF10ops’ was discovered by the supernova zoo using images from the Palomar Transient Factory Telescope in California and a report on this interesting SN has now been accepted for publication in the journal, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Thanks to the very rapid discovery of this supernova by members of the supernova zoo, we were able to start taking observations very soon after explosion with many telescopes around the world such as the 4.2 m William Herschel Telescope on the Canary Island of La Palma, the 3 m Shane telescope at the Lick Observatory, California and at one of the two 10 m telescopes located at the Keck Observatory in Hawai’i.

An image of the field of PTF10ops (located at the centre of the crosshairs) taken with the WHT+ACAM on La Palma, Canary Islands. The largest galaxy with spiral arms located in the upper left quadrant is the host galaxy of PTF10ops, located at a distance of 148 kpc from the supernova position. This is the largest separation of any SN Ia discovered to date.

PTF10ops turned out to be a very interesting supernova – a peculiar type Ia supernova. Type Ia supernovae are explosions that occur when a white dwarf (a small, dense star) collapses when it pulls matter from a companion star and grows to have a mass of more than 1.4 times that of the Sun. At this critical mass, a thermonuclear reaction is triggered, that destroys the star in a massive explosion that we call a type Ia supernova. Type Ia supernovae are very important because they are used as cosmological distance indicators and were used in the discovery that the expansion rate of the universe is accelerating.

PTF10ops had unusual observational properties that suggest that maybe a new type of supernova explosion has been discovered. It is located very far from its host galaxy, actually the farthest supernova from the centre of its host galaxy discovered to date. Its spectra also contained signs of rare elements such as Titanium and Chromium. In normal Type Ia supernovae, how long a supernova stays bright is directly related to its peak brightness, but PTF10ops did not follow this rule and stayed brighter for much longer than expected. It is still unclear what it was about the star that exploded that produced this unusual supernova, maybe it was very old star or maybe we are seeing some sort of new, unknown explosion.

In the future, we hope to take images of more objects like this using the Palomar Transient Factory and then with the invaluable help of the supernova zoo members, we can catch these supernovae very soon after explosion and start follow up observations immediately to get images and spectra to better understand these rare supernova explosions.

P.S. Here’s the piece of the paper crediting the discoverers – well done all!

Star formation rate vs. color in galaxy groups

Toady’s guest blog is from Andrew Wetzel, a postoc at Yale University. We asked Andrew to write this blog since he and his collaborators had used the public Galaxy Zoo 1 data in their own work (that is, they weren’t part of the team). Without any further ado, here’s Andrew’s experience with the Zoo data:

Recently, Jeremy Tinker, Charlie Conroy, and I posted a paper to the arXiv (click the link to access the paper) in which we sought to understand why galaxies located in groups and clusters have significantly lower star formation rates, and hence significantly redder colors, than galaxies in the field. Among the interesting things we found is that the likelihood of a galaxy to have its star formation quenched increases with group mass and increases towards the center of the group. Furthermore, galaxies are more likely to be quenched even if they are in groups as low in mass as 3 x 10^{11} Msol (for comparison, the `group’ comprised of the Milky Way and its satellites has a mass of about 10^{12} Msol). All together, these results place strong constraints on what quenches star formation in group galaxies. However, many of the above results disagree with what some other authors have found recently, and here is where Galaxy Zoo has been useful for us.

Because galaxies that are actively forming stars have a significant population of young, massive, blue stars, while galaxies that have very little star formation retain just long-lived, low-mass, red stars, astronomers often differentiate between star-forming and quenched galaxies based on their observed color. But using observed color can be dangerous, because if a galaxy contains a significant amount of gas and dust, it can appear red even if it is actively star-forming (analogous to how the sun appears redder on the horizon as the light passes through more of Earth’s atmosphere). To get a more robust measurement of a galaxy’s star formation, we used star formation rates derived from their spectra, because spectroscopic features are fairly immune to dust attenuation. But, we wanted to check how these spectroscopically-derived star formation rates compare with the color-based selection that many previous authors have used. What we found was striking: in lower mass galaxies, over 1/3 of those that appear red and dead actually have high star formation rates!

What is going on? Here is where Galaxy Zoo provided us with insight. We examined the Galaxy Zoo morphologies of these red-but-star-forming galaxies, and the result was telling: 70% of these galaxies are spirals (which have particularly high gas/dust content) and furthermore, 50% are edge-on-spirals (for which the dust attenuation is particularly strong). The image shows a good example of a galaxy which has a high star formation rate but appears red. You can even see the dust lane.

So, Galaxy Zoo helped to confirm our suspicion that many spiral galaxies that appear red are in fact actively forming stars, but their colors are reddened via dust (Karen Masters has done a lot of work in this direction as well). This gave us further confidence in our spectroscopic star formation rates and insight into why previous authors, using observed color, came to such different conclusions. Thanks to the Galaxy Zoo team and all the volunteers.

Voorwerpje paper submitted

Bill has written an excellent post about the Voorwerpje, or small Voorwerp, hunt over on the main Zooniverse blog. You should read it!