First Supernova Paper Accepted

The true test of any citizen science project is whether it actually makes a contribution to science. That contribution can be small, but the thought that you’ve made a difference, no matter how small, to what is known about the Universe is a fine one. We know from the interviews our education research team have conducted that it motivates you too, so I’m delighted to announce that the first paper from Galaxy Zoo : Supernovae has been accepted by the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. With the first Zoo 2 paper published by MNRAS this week, it’s in danger of becoming our in-house magazine (!), but this is seriously great news.

The home of the Palomar Transient Factory

The paper, put together by 24 authors from the Zooniverse and the Palomar Transient Factory along with classifications from nearly 3000 Zooites, reports the results from the early trials of the supernova project which ran between April and July 2010. If you’ve been following the progress of the project, then it’ll be no surprise that things went well. In fact, the results are remarkably good. From the nearly 14000 candidates processed in that time, we caught 93% of the supernovae in the sample, and not a single candidate identified as a supernova by the Zoo was a false alarm.

The key to this result is the scoring system the Zoo uses. Depending on the answers to the question presented, candidates end up with a score of -1, +1 or, for really promising candidates, +3. If the average is above 1, then the candidate is probably a supernova. The team conclude that there is room for improvement here, particularly in reducing the number of classifications needed for a definitive decision. This isn’t that important right now, as the classifiers signed up to our email alerts are doing a sterling job, but as we expand to include more data, including supernovae from other surveys, it will become more important.

For now, though, please do consider helping out. Our latest paper shows that you’ll be making a real difference to PTF’s search for the exploding stars that might reveal our Universe’s fate.

Chris

P.S. On a personal note, congratulations to lead author Arfon on his first paper as lead author since leaving astronomy for web development a few years ago….

The Sudden Death of the Nearest Quasar

When I told Bill Keel the results of the analysis of the X-ray observations by the Suzaku and XMM-Newton space observatories, he summed up the result with a quote from a famous doctor:

“It’s dead, Jim.”

The black hole in IC 2497, that is.

To recap what we know: the Voorwerp is a bit of a giant hydrogen cloud next to the galaxy IC 2497. The supermassive black hole at the heart of IC 2497 has been munching on vast quantities of gas and dust and, since black holes are messy eaters, turned the center of IC 2497 into a super-bright quasar. The Voorwerp is a reflection of the light emitted by this quasar. The only hitch is that we don’t see the quasar. While the team at ASTRON has spotted a weak radio source in the heart, that radio source alone is far too little to power the Voorwerp. It’s like trying to light up a whole sports pitch with a single light bulb – what you really need is a floodlight (quasar).

Now it is possible to hide such a floodlight. You just put a whole bunch of gas and dust in front of it. If there’s enough material, no light even from a powerful floodlight will get through. Imagine pointing it at a solid wall – even the brightest floodlight in the world will be completely blocked by the wall. In the realm of quasars, such a barrier is usually made up of the torus of material (gas and dust) spiralling in towards the black hole and settling into an accretion disk. So you can have quasars that are feeding at enormous rates and being correspondingly enormously bright, but our line of sight is blocked.

So there are two possibilities of what could be going on with IC 2497 and the Voorwerp:

1) The quasar is “on” but hidden by lots of gas and dust, or

2) The quasar switched off recently, but because the Voorwerp is 70,000 light yeas away, the Voorwerp is still seeing the quasar – after all, even light takes a while to travel 70,000 light years. This would make the Voorwerp a “light echo.”

So how do we distinguish between the two possibilities? The best way is to look at a part of the electromagnetic spectrum that generally has no trouble penetrating even thick walls: X-rays!

If the quasar in IC 297 is feeding, then we should see the X-ray light it is emitting even through the thickest barriers. That’s why we asked for observations with Suzaku and XMM-Newton. It took many months to gather and analyze the data before we were ready to write up a paper and submit it to the Astrophysical Journal as a Letter. The referee report was challenging but positive, and the Letter got accepted rapidly. The pre-print is now out on arxiv: http://arxiv.org/abs/1011.0427

So what did we find? We found something, but it isn’t a quasar. With the X-ray data, we can definitely rule out the presence of a quasar in IC 2497 powerful enough to light up the Voorwerp. We do however see some very weak X-ray emission that most likely comes from the black hole feeding at a very low level. Compared to what you need to light up the Voorwerp (the floodlight), the black hole currently puts out 1/10,000 of the required luminosity. That’s like trying to illuminate a sports stadium at night with a candle.

We can therefore conclude that the black hole in IC 2497 dropped in luminosity by a factor of ~10,000 at some point in the last 70,000 years. This implies a number of very exciting things:

1) A mere 70,000 years ago (a blink of an eye, cosmologically speaking), IC 2497 was a powerful quasar. Since it’s at a redshift of only z=0.05, it’s the nearest such quasar to us. Since IC 2497 is so close to us, and the quasar has switched off, it means that images of IC 2496 are the best images of a quasar host galaxy we will ever get.

2) Quasars can just switch off very quickly! We didn’t know they could do this before, and the fact that they can is very exciting.

3) Maybe the quasar didn’t just switch off, but rather switched state, and is now putting out all its energy not as light (i.e. a quasar), but as kinetic energy. That’s an extremely intriguing possibility and something I want to investigate.

—————————————————————-

We put out a press release via Yale. You can find it here.

Galaxy Zoo: Hubble – Now in German

Galaxy Zoo: Hubble is now available in German! The likes of Johannes Kepler, Heinrich Olbers, Joseph von Fraunhofer and Max Planck would all no doubt be very pleased, as we’re sure they would have loved Galaxy Zoo!*

German is one of the most important cultural languages in the world. Many famous figures, such as Beethoven, Freud, Goethe, Mozart and Einstein spoke and wrote in German. It is the language of around 100 million people worldwide, not just in Germany, but in Austria, a large part of Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, the South Tyrol region of Italy, parts of Belgium, parts of Romania and in the Alsace region of France.

Galaxy Zoo: Hubble is proud to finally be available in German and here at Zooniverse HQ, we’re very grateful to our friends at the Center for Astronomy Education and Outreach in Heidelberg, who helped us make it happen. Since Galaxy Zoo began, German speakers have provided millions of clicks for the project and we hope that this will encourage them even more.

Auf Wiedersehen,

The Zooniverse Team

*Admittedly, this is hard to verify.

An Extra-galactic Halloween

At a pumpkin carving event yesterday, we (a group of people from Yale astro) tried to come up with an appropriate theme for our pumpkin. Naturally, we decided on the Hubble Sequence of galaxy morphology:

Elliptical

Lenticular

Early Spiral

Late Spiral

Irregular

And the artists…

A Train-wreck in Pisces

This weeks OOTW features Lightbulb500’s OOTD posted on the 22nd of October 2010.

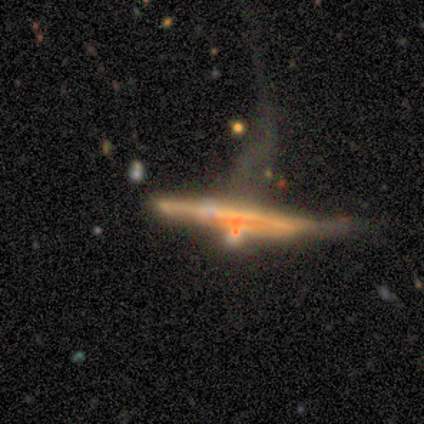

1 billion light years away a cosmic train-wreck of two merging galaxies is taking place, throwing stars out in streamers stretching out for thousands of light years in a flurry of gravitational disruption. Deep within this train-wreck at least one super massive black hole has awakened as a result of the infalling matter from the merger, making it a Seyfert 1 galaxy according to SIMBAD.

A seyfert 1 galaxy is a galaxy host to an AGN (Active Galactic Nucleus). The matter falling into the black hole forms an accretion disk which in turn creates massive jets of plasma as the disk emits huge amounts of radiation as a result of friction. This radiation gets concentrated into jets of plasma that beam out for thousands of light years!

The angle of the jets mostly determines what type an AGN is. There are several types such as the Blazars, the Seyfert 1’s, seyfert 2’s and so on. This galaxy is a seyfert one so the jet is beaming out at around 30 degrees so that it’s not quite facing us directly. A blazers jet would be facing directly at us, and the jets of a seyfert two would be at pointing 90 degrees away from us.

Eric F Diaz commented in the OOTD thread and asked if the galaxy is a polar ring or not, and Lightbulb500 set up a poll to see what everyone thought.

A polar ring galaxy is where a galaxy punches through the centre of another and as a result this creates a ring. This ring sorrounds and orbits the galaxy at its poles, creating wonderful images like this:

John Huchra

I’m going to take a little time to tell you about John Huchra and even if his name isn’t familiar yet, I hope you’ll understand why when I’m done. I don’t think anyone would disagree with me when I say that John Huchra (1948-2010) was a great astronomer, and a great man. His impact is felt in many areas of extragalactic astronomy, but in particular he leaves an immense legacy in our progress in mapping the universe.

John Huchra (2005)

In the 1980s, John (working with his collaborator Margaret Geller and others) published a new map of part of the universe (see below). John was an enthusiastic observer, and much of the data in the below figure comes from his long nights at the telescope. What the below shows is the position of galaxies in a slice from 8h-17h in right ascension and between 26.5-32.5 degrees in declination (a long and skinny strip which starts near “the twin stars” in Gemini and passes through Coma and Bootes ending in Hercules). In this strip galaxies are then spread out according to their redshift which because of Hubble’s Law acts as a proxy for distance.

The below image became famous because of the so-called CfA Stick Man (CfA after the Center for Astrophysics where the work was done). This “stick man” indicates the position of the Coma cluster (in the Coma constellation) where there is a large collection of galaxies, and where redshifts no longer equate so well to distance because of the large motions of the galaxies around the centre of mass of the cluster. This means in a redshift plot, all the galaxies get spread out in along the line of sight, and in this particular map end up looking like a stick man!

Distribution of galaxies in the CfA Redshift Survey

For astronomers this diagram showed conclusively that galaxies were not distributed randomly in the universe, and led to a complete revision of the way astronomers thought about the formation of galaxies. John and his collaborators got it absolutely right in their abstract which ended “These data might be the basis for a new picture of the galaxy and cluster distributions.”

John never stopped mapping the universe, and one of his passions was for measuring galaxy redshifts. For a most of his career this was a painstaking and time consuming process of taking spectra after spectra of single galaxies. But this process was clearly something John loved (as you can see for yourself if you ever find a copy of “So Many Galaxies, So Little Time” which is unfortunately not yet on YouTube!).

In fact John’s legacy in this area is not quite finished. He has a continuing program (The 2MASS Redshift Survey) on the CfA’s Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory in Arizona to measure redshifts for all galaxies in 2MASS (an all-sky survey in the near infra-red) to a fixed brightness limit (just over 40,000 galaxies in total) which just needs a handful more observations to be complete. John was also involved in some of the more modern galaxy redshift surveys, which use multi-object spectrograph (instruments which can take spectra of many galaxies at once) – especially the 6dFGRS (6dF galaxy redshift survey) in the southern sky (which is the southern part of the 2MASS redshift survey).

Along with redshifts, John was very interested in measuring direct distances to galaxies and pinning down the value of the Hubble Constant (the scaling factor between redshift and distance in Hubble’s Law). He was involved in the famous Hubble Key Project which measured H0 to 10% accuracy. The below picture shows many of the people involved in that project at the meeting where it was initiated.

John (kneeling) in 1985 at a meeting on the Cosmic Distance Scale at the Aspen Center for Physics.

John kept track of all published determinations of the Hubble Constant, and the below figure was posted on his office door at CfA showing the many published determinations of H0 since 1920 (based on data in his publicly available file hubbleplot.dat which you might notice is up-to-date until mid-2010).

Published values of the Hubble Constant

He also has a more complete History of the Hubble Constant, which explains all of this and is well worth a read.

I had the honour and privilige to work with John Huchra during my postdoctoral appointment at Harvard (2005-2008). I was hired to work on the 2MASS Redshift Survey, and ended up initiating a program to measure distances to some of the brighter spirals in it (using a relationship between how fast spirals rotate and how bright they are). I was working at Harvard when I first learned about the Galaxy Zoo project (from the BBC press at its first release). John and I did discuss Galaxy Zoo and it was definitely something he was interested in. In fact, many of the “professional” morphological classifications you can find (for example published in the NASA Extragalactic Database) come from John, and while I was at Harvard he was working on completing his personal morphological classification of the brightest half of the 2MASS Redshift Survey (roughly 20,000 galaxies). He just liked looking at galaxies I think.

John’s contributions to astronomy are immense. A search for his publications in the online database ADS will tell you that over his 40 year career he was involved in more than 700 papers, with a combined number of over 30,000 citations. Many of these papers are with students and postdocs he mentored, and he leaves a massive contribution in this area too – mentoring not only those who formerly worked with him, but so many others informally at conferences and meetings. John always had time for a chat.

John Huchra died on 8th October 2010. His death seemed sudden and unexpected to many in the astronomical community, perhaps because John was extremely visible right up until his death. He had only just stopped being the President of the American Astronomical Society, and had participated heavily in the US Decadal Survey (ASTRO 2010).

John had however had serious heart problems following a heart attack in 2006, and it seems had personally known his days were numbered. I like to believe he made a conscious choice to remain working in the field he loved, while enjoying his remaining time with his wife and teenage son. It will never have been enough time, and his loss (both personally, and to the field of astronomy) is deeply felt.

John is remembered in obituaries in The New York Times, and The Telegraph, as well as blogs from Cosmic Variance, and The Bad Astronomer, and Astronomy Now

He has a short autobiography on his website where you can read about him in his own words circa 1999. The rest of his website is also a treasure trove of useful information and links.

John, by definition, we’ll miss you.

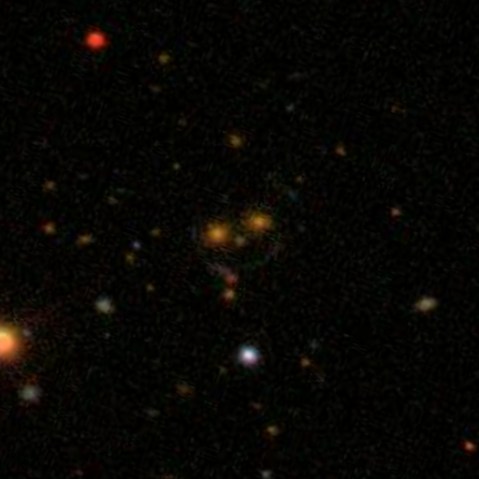

The Smiling Lens

This weeks OOTW features Jean Tate’s OOTD posted on the 20th of October 2010.

This is SDSS J103843.08+484916.1. It’s a gravitational lens in Ursa Major that Jean calls the ‘Smilie’; and you can see why!

So what is the cause of the arcs around the central galaxies?

Gravitational lensing is due to the curvature of space. Think of a bowling ball on a trampoline, the trampoline is the fabric of space and the bowling ball is the mass – say a cluster of galaxies – bending it. The more mass the bowling ball has the more it will bend the trampoline, and the same goes for objects in space.

The arcs are in fact distorted images of a galaxy that is lurking behind the central galaxies you can see in the image; you can see it much clearer in this Hubble images here. The light from the galaxy behind has followed the curvature of space caused by the huge mass of the central objects, making the light bend around the galaxies as arcs.

The left golden fuzzy has a redshift, Z, 0f 0.426, making it around 4.5 billion light years distant. The galaxy that forms the arcs however could be much further away.

Hunting Voorwerpjes

The discovery of the Voorwerp is definitely still keeping us busy as we’re trying to understand it. To recap what we know: the Voorwerp is a bit of a giant hydrogen cloud next to the galaxy IC 2497. The supermassive black hole at the heart of IC 2497 has been munching on vast quantities of gas and dust and, since black holes are messy eaters, turned the center of IC 2497 into a super-bright quasar. The Voorwerp is a reflection of the light emitted by this quasar. The only hitch is that we don’t see the quasar. While the team at ASTRON has spotted a weak radio source in the heart, that radio source alone is far too little to power the Voorwerp. It’s like trying to light up a whole sports pitch with a single light bulb – what you really need is a floodlight (quasar). We’ve been working hard on the X-ray observations that will give us a final answer whether there’s a quasar clevely hiding in IC 2497, or whether the black hole has somehow abruptly stopped feeding.

In the meantime, what we want to know is if there are more Voorwerps, or if Hanny’s Voorwerp is all we have in the local universe. This turns out to be harder than it sounds because asking a computer to go search a massive data set like Sloan for smudges that have this weird blue-purple-y colour is rather difficult. In fact, the Computer said ‘no.’ Fortunately, we could ask you folks to find weird blue-purpley-y stuff around galaxies because such a vaguely phrased question of a human makes sense. And you found more Voorwerps. Since they’re smaller, we dubbed them Voorwerpjes, or `Little Objects’ in Dutch (I look forward to the day that ‘Objects’ are a class of astronomical objects!).

Bill and his team have been taking a look at all the potential Voorwerpjes that you found and many of them are similar to the Voorwerp in the sense that they are clouds of gas lit up by an accreting black hole. All these clouds, like the Voorwerp, are many tens to hundreds of thousands of light years away from the centers of the galaxies they surround. So like with the Voorwerp and IC 2497, we know for a fact that the black hole was feeding tens to hundreds of thousands of years ago. What we’d like to know is if they are still feeding. If not, then clearly black hole meals can end rather abruptly (10,000 years is nothing to a billion solar mass black hole). If that’s the case, then black hole feeding is stranger and less stable than we previously thought….

To find out, we submitted a proposal, again to our friend XMM-Newton, to take X-ray snapshots of the galaxies with the top Voorwerpjes. Fingers crossed that we get the time.

Bar Papers – one submitted, one accepted!

Good news for Galaxy Zoo 2 bars this week.

To start with, the first bar paper (and the first ever using Zoo2 classifications) has just been accepted. I discussed our findings on the blog just after it was submitted way back in February. A lot has happened since then, and the length of time between submission and acceptance in this case has less to do with the speed of the peer review process, and more to do with me being otherwise occupied (my son was born 4 days after the paper was submitted). But anyway it’s been accepted now, and the final version will be available on the ArXiV later this week.

And if that wasn’t enough, Ben has just submitted the first paper from the bar drawing project. We’re very excited about this result, and we’ll keep you posted as it progresses through the peer review process.

Thanks again for all the clicks – and measurements!

Karen.