Win a Signed Comic Book

With the launch of the comic ‘Hanny and the mystery of the Voorwerp’, we’re also launching a competition. So here’s your chance to win a copy of the book, signed by Hanny!

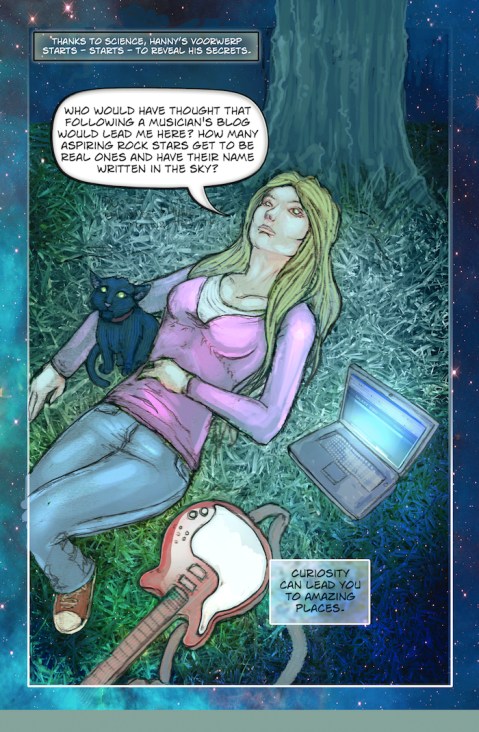

What you need to do: take a good look at the page published below – it’s one of the pages from the comic – and answer the following question: This scene might have happened in the real world as well as the comic – except for one thing. What is it?

All answers (serious and/or creative) can be sent in by commenting on this blog. (Note that the first set of books will have this page in it, but the improved page is already ready to be seen by the world too.)

Good luck!

The Stellar Nursery of Perseus

Today’s OOTW features Alice’s OOTD written on the 2nd of September 2010.

This is NGC 1491, a HII region lurking in the Perseus constellation just above the star Lambda Persei.

HII regions are what they say on the tin; they are made of of hydrogen gas, a considerable amount of which has been ionized by radiation coming from the shorter wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum.

HII regions are ionized after a nebula has finished forming a new batch of stars; the regions that shroud the stars get blown away by the winds given off by the stars, creating the bubbles and filaments in the nebula. As these stars emit huge amounts of ultraviolet light they ionize – meaning the ultraviolet light shoves off the electrons from the atoms that make up the hydrogen gas – everything surrounding them, heating up the clouds of nebulous material and lighting it up, creating great eye candy for us!

Alice gives us different views of NGC 1491 in her OOTD, such as this lovely one:

I couldn’t resist having a go at playing around with the SDSS fits files on DS9 so I put this image together using I, R and G fits files:

NGC 1491

Unfortunately I couldn’t find any files that give the full view of the nebula!

And to quote Alice:

Why a nebula? Because nebulae might well soon be on the menu. They’re part of Project IX, whose exact definition is still . . . well . . . nebulous! Well, let’s collapse those clouds and make it less so. Can you suggest a name? They’re looking forward to hearing from you!

"Hanny and the Mystery of the Voorwerp" goes live!

Here we are again, representing Galaxy Zoo at Dragon*Con. This is an enormous gathering of science-fiction and fantasy fans, aficionados of science, gaming, costuming, offbeat music – all packed into downtown Atlanta’s five largest conference hotels, every Labor Day holiday weekend. It’s a huge Con – the number of people here at one time or another during last year’s event was nearly one-quarter of the total number of people who have ever signed up for the Zooniverse projects.

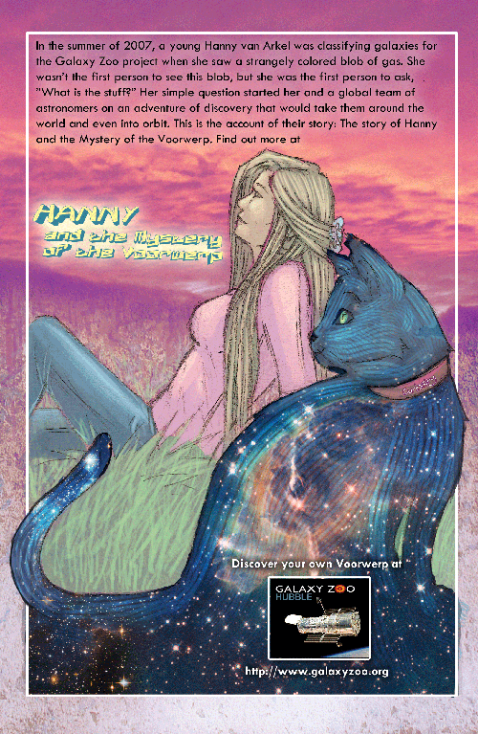

An earlier post told of our presentations in a citizen-science panel in 2008. This year, we’re more deeply involved in several themes represented by attendees – astronomy, citizen science, writing, art, and comics. I refer, of course, to the (web)comic Hanny and the mystery of the Voorwerp, which will be released at a launch event Friday night. (Data from several satellites, including the Hubble Space Telescope, are involved, so of course we would start it with a launch). This is a public-outreach project funded by NASA, through the Space Telescope Science Institute, telling the story first of Hanny’s discovery of the Voorwerp, and then of the efforts of many of us to find out what it is and what makes it shine. Pamela Gay, who has been part of the Zoo education team for several years and is well known as a pioneer in using electronic “new media” to communicate science, took the leading role in organizing the project.

In true Zoo style, the writing of the script was a collaborative effort, carried out at the CONvergence meeting in Minneapolis. Under the watchful eye of fact-and-fiction author Kelly McCullough, the story took shape with a cast mostly composed of interested volunteers attracted by the opportunity. Things then sped up – we had to make the deadline to get some printed copies for Dragon*Con, the last such big event of the year. In the end, I’m very pleased with the result, both artistically and educationally, Kevin looked at proofs and mentioned being gratified at how many bits of science we smuggled in (more or less) painlessly. The combination of line artits Elea Braasch and colorist Chis Spangler worked beautifully, giving a very impressionistic feel to some of the panels. (It was an unexpected bonus that Elea improved dramatically on my actual hair).

The opening event is at 10 p.m. EDT on Friday, September 3. That’s 0200 UT on the 4th – 3 a.m. UK summer time and 4 a.m. across the Channel. Nonetheless, Hanny plans to Skype in so the crowd can “meet” her live. They have booked the Crystal Ballroom at the Hilton for the event. Oddly enough, this is a prime event time for the Con, where things happen 24 hours each day. (In fact, I head afterwards to one of my nightly Live Astronomy events where I’ll be taking requests for objects to take images of with a telescope in Chile). We’ll start with a short talk on the discovery and scientific interest of the Voorwerp, some background on the webcomic, handing out print copies to people there, Hanny’s remarks, door prizes, and a “dress like a Voorwerp” contest. (I have been too busy to find out what kind of material glows bright green under UV light, which would be just the thing.) For those not able to join us in Atlanta, the event will be videocast via UStream. That link also gets you to a form allowing you to order printed copies shipped anywhere at cost, and downloads of promotional posters and cards. Since it’s a webcomic, you can also read it online here once we’ve started the premiere event.

Live or virtual, please join us, and share in the story…

Why build the Hubble Space Telescope?

After I had started my post about the planning phase of the HST up to the start, I have noticed that the arguments (which I thought to be a small section in there) for building a Space Telescope in the first place took up quite some space, so I have decided to post this for now and delay the rest of the post into a different one (trying to keep the posts from getting too extensive as I promised last time), possibly the next.

At first sight it doesn’t sound like a terribly good idea to put an expensive telescope on an expensive rocket (which doesn’t mean it’s a successful start at all, usually expensive equipment and large quantities of explosives are kept well apart for a reason) and shoot it into orbit where again many things can (and did) go wrong and telescope maintenance is either impossible or at least very expensive. Why not simply build a ground-based telescope which is a lot cheaper but would still have a much bigger mirror (so can collect more light and potentially create sharper images, see below) and would still be much cheaper and easier to maintain? Where a new camera simply needs to be screwed on (a simplification about which many telescope engineers could rightfully complain), rather than having to employ the (again expensive) space shuttle to even get there in the first place and then having to work in unhandy space suits to get the new equipment in (with the risk to notice that a bolt might be too long and the camera doesn’t even fit in); and if it doesn’t work afterwards, you’re screwed and you cannot simply take it down again and fix it? Not even talking about potentially simple problems like cooling the camera chips for which you need liquid nitrogen or helium, which, on earth, you can simply refill with a tank, but which in space becomes a rather more complicated task altogether.

So at first sight, it looks like people need a very good reason to even think about Space Telescopes, an then start developing, maintaining and upgrading one with new cameras. So what are these advantages that made scientists built the HST (and many other Space Telescopes)?

Well, there are 2 main reasons, one of which solves a problem that was at least impossible to overcome back then and one that solves a fundamental problem alltogether:

The first problem: In principle, the angular resolution of a telescope should be given by the wavelength of the observed light and the diameter of the mirror (or lens). This is simple optics that every physics student learns and it says that the bigger a mirror, the better the resolution. But there is one very large problem: This is pure theory for an ideal telescope in a vacuum. As in the old physicist joke: ‘Yes, I’ve got a solution, but it only works for spherical elephants in a vacuum’. But here, talking about telescopes instead of elephants, the problem really IS the atmosphere which changes the situation completely.

The first problem: In principle, the angular resolution of a telescope should be given by the wavelength of the observed light and the diameter of the mirror (or lens). This is simple optics that every physics student learns and it says that the bigger a mirror, the better the resolution. But there is one very large problem: This is pure theory for an ideal telescope in a vacuum. As in the old physicist joke: ‘Yes, I’ve got a solution, but it only works for spherical elephants in a vacuum’. But here, talking about telescopes instead of elephants, the problem really IS the atmosphere which changes the situation completely.

The atmosphere has its upsides for breathing, weather (sometimes we could do with a bit less atmosphere here in England 😉 ), airplanes and stuff, but for astronomers, it’s really just ‘in the way’. The air, or better to say the movement of the air, the turbulences of hot and cold air bubbles, bends the starlight on its way into the telescopes (very much like when you’re looking over the tarmac on a very hot summers day everything is flickering). This basically makes stars jump around very fast (Actually, you can see this effect by looking at the stars. Stars ‘flicker’ at night. Objects larger than this effect, e.g. planets, don’t flicker; That’s how you can tell them apart easily). As the apparent position of the stars jump around faster than the eye or a normal camera can detect, it doesn’t really make stars move in long-time exposures, but it leads to ‘blurring’ of the image (If you want to know what a stars picture actually looks like in extremely short exposures, read this article).

This effect is so big that it easily overpowers the resolution improvement due to a bigger mirror size. In fact, to get the maximum resolution of a telescope at sealevel, a telescope with something between 10 and 20 cm diameter is big enough. Any bigger than that does not increase the image resolution due to seeing. Groundbased telescopes can therefore not see details smaller than 0.5-1.0 arcsec in size, even at the best telescope sites (which are usually in very dry places very high up. Dry weather is usually less turbulent and building telescopes at high altitude avoids having to look through large parts of the atmosphere in the first place, so ‘seeing conditions’ are usually better). For comparison, the Hubble Space Telescope has a resolution of only 0.05 arcsec due to it’s position outside the atmosphere and its size of around 2.5 meter.

I show the effect of seeing in the images above. The top one is a picture taken by a 2.2 meter (so similar to HST) telescope in Chile from the Combo-17 survey. The bottom one is the same area of the sky taken by HST (to be precise, it’s a small bit of the Hubble Ultra Deep Field H-UDF, stay tuned for one of my later posts about this survey). You can clearly see that all the objects in the groundbased survey are blurred and some of the faint objects are actually blurred so much, that they cannot even be seen at all above the sky background. In the space based image, the details and features of the galaxies are visible much more clearly. This is the reason why these images were now chosen to be classified in Galaxy Zoo: Hubble. From groundbased telescopes a classification of galaxies at similar distances is simply not possible.

Of course, a big telescope has another obvious advantage: It collects a lot of light, so it enables us to see fainter objects. This is the main reason why telescopes in the past were built bigger and bigger and this trend continues even today.

Also, there are a few things that can be done to improve the image quality, but most of them go beyond the scope of this blog, but if you want to know about it, read e.g. this article and links therein. Basically, either interferometry (where several telescopes far apart are used, unfortunately, this does not produce a full ‘image’ of the object) or movable and distortable mirrors can be used. The latter is called adaptive optics, a very complicated and expensive technique, in which the wavefront of the starlight that has been distorted by the atmosphere can be corrected by a mirror, which is generally speaking distorted exactly in the opposite way to make the wavefront flat again (The mirrors shape has to be adjusted around 200 times per second). A flat wavefront will create a sharp – ‘diffraction limited’ – image, using the complete power of the big mirror used. Adaptive optics was only developed in recent years on several telescopes. The Hooker telescope mentioned in my last blog runs one, for example, and most big telescopes like Gemini, Keck or the VLT run these facilities, too. Although I did call this technique ‘expensive’, it is, of course, a lot cheaper than building a Space Telescope.

In fact this is one of the reasons why the HSTs ‘successor’, the JWST telescope (also one of my later posts) will not be observing at the same optical wavelengths as HST but will rather concentrate on IR wavelengths. Running adaptive optics facilities, groundbased telescopes now produce images of the same quality as the HST, although on a smaller field of view and only close to stars (they need bright-ish stars to compensate the effect of the atmosphere, although laser guide stars will avoid at least the second problem in the future). The 30-40 meter telescopes that are currently planned around the world will show much better resolution again and using very sophisticated adaptive optics might have a similar or even bigger field of view as HST currently has. In the image below (please click for full resolution), you can see an estimated example for a telecope called OWL (Overwhelmingly Large telescope, not kidding, the image above shows a simulation. The speck in the foreground is a car for size comparison). This was a planned telescope which has now been cut down to 42 meters, we now call it the E-ELT (the Extremely Large Telescope, yes, astronomers are not very creative when it comes to telescope names). It’s design is different (but OWL of course is more impressive and their website provided the images I was looking for), but very recently, its cite has been selected to be on a neighbouring mountain to Cerro Paranal, the cite of the VLT.

As you can see on the left, this telescope would, with perfect adaptive optics (diffraction limited) indeed produce much sharper images with much higher resolution then even HST can provide today. So in principle, the problem of the atmosphere can be overcome using clever techniques. The field of view on which this works today is still a lot smaller than what is covered by HST survey cameras, but this is a matter of technique and might be overcome in the future (if interested, google ‘multiconjugate adaptive optics’). In the past, when HST was planned, non of this existed, so a Space Telescope indeed sounded like a good idea.

But groundbased telescopes have an even more fundamental problem which is simply put impossible to overcome. At ground level, only certain wavelengths in the electromagnetic spektrum can be observed. (Far) Infrared, ultraviolet and gamma light cannot be observed at all from groundbased telescopes as the light is strongly absorbed by the atmosphere. The image on the right shows the height above ground at which light is basically absorbed by the atmosphere. As you can see, only optical and radio (and a bit near infrared) observatories make sense on earth, even on the highest mountains. For any other wavelength, you need a space telescope to be able to observe galaxies at all.

But groundbased telescopes have an even more fundamental problem which is simply put impossible to overcome. At ground level, only certain wavelengths in the electromagnetic spektrum can be observed. (Far) Infrared, ultraviolet and gamma light cannot be observed at all from groundbased telescopes as the light is strongly absorbed by the atmosphere. The image on the right shows the height above ground at which light is basically absorbed by the atmosphere. As you can see, only optical and radio (and a bit near infrared) observatories make sense on earth, even on the highest mountains. For any other wavelength, you need a space telescope to be able to observe galaxies at all.

NGC1512 screengrab from Wikipedia

Different wavelengths can be very interesting, a galaxy looks completely different in optical than in X-ray or Radio and all these wavelengths show different physical parameters, e.g. star formation rates (X-ray) or the amount of ‘dust’ in the galaxy (in IR). A good and famous example for this is NGC 1512, a barred spiral galaxy whose center has been observed at different wavelengths by the same telescope. You can see the results on the right. Generally speaking, very blue light (shown in purple) shows very young stars, redder light (up to orange) older stars, red shows dust. Remember, these are all still more or less optical wavelengths, in X-ray or far infrared, this galaxy would look even more different.

The HST works at optical wavelengths, so this was not really a reason to build it, most things (although HST does have some IR filters) could indeed be observed by groundbased telescopes. But as I mentioned above, the HSTs successor, the JWST will exclusively be working in IR for exactly this reason. Optical cameras are not really needed in space anymore (although it’s of course a shame that we won’t have an optical space telescope in the future), but for IR observations it’s vital to be in space. Other famous Space Telescopes in other wavelengths include Spitzer (IR), Chandra (X-ray), GALEX (UV) and XMM-Newton (Xray), all of which are impossible to be replaced by earth-bound instruments.

There are also quite a few focused satellites for certain experiments in space, e.g. WMAP (to observe the afterglow of the Big Bang), Keppler (to detect exo-planets, planets around other stars than the sun) and others, but these are focused projects and not open telescopes everybody can apply to, which of course everyone can at the HST. I will talk about this and some big projects that successfully got their time on the HST in my future posts.

All in all, you can see, there are several good reasons to build a Space Telescope, scientists don’t do this because it’s ‘fun’ or ‘cool’. For observations in certain wavelengths it is still important today, for others it has at least been important in the past. Which brings us back on track: At some point, the decision was made to build the HST (although it wasn’t named Hubble then) and the planning began. But this will be my next post, so stay tuned. I am travelling a lot in the next month, so I might not be able to hold the 2-week schedule, but I’ll do my best.

Cheers,

Boris

Previous history of this series:

- August 2nd, 2010: Me, HST and the History of Surveys

- August 16th, 2010: Edwin Hubble, the Man behind the Telescope

A star with a full house

This week’s OOTW features Lightbulb500’s OOTD posted on the 27th of August.

HD 10180; Credit: ESO

This star, HD 10180, lurks in Hydrus 127 light years away. It’s a sun-like star, and through 190 observations of the stars wobble with the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (phew) it is found to have five gas giants, and two more wobbles are suspected to be due to two or more additional planets! One it has been proposed is another gas giant, much like Saturn, and the second planet is thought to be Earth-sized, but although it could be the right size for life, its orbit around HD 10180’s solar system certainly isn’t the best at 0.02 arc seconds from the star, to give you an idea of how close that is, it orbits its star in 1.8 Earth days! Toast anyone?

Read more about this planetary system here, and there’s a wonderful video on the system here!

X-ray paper submitted!

Just a quick note: I’ve finally submitted the paper on the X-ray observations of IC 2497 and the Voorwerp with XMM-Newton and Suzaku. It’s a Letter so we should hear back fairly soon, so stay tuned!

Preethi's Cross-Eyed Galaxy

Remember this object from back in February? It turned up in a paper that I was reading today, going by the name of Preethi’s cross-eyed galaxy.

The paper, by Preethi Nair (now in Italy) and Roberto Abraham from the University of Toronto, is going to be really important as we analyze data from Zoo 2 and from Galaxy Zoo : Hubble. As part of her thesis work, Preethi examined over 14000 galaxies – twice each, to check for consistency (!) – in order to produce the largest detailed morphological catalogue in existence. We’ll be comparing your results to hers, and hopefully showing that the classifications for the other 280,000 or so galaxies in Zoo 2 are as reliable as her 14,000.

Or at least, that’s the theory. In practice I’ve spent the day trying to be sure I understand which of her objects match which of ours. But seeing an old friend – albeit with a new name – crop up still made me smile.

A Comic Voorwerp

This past Monday, at about 8pm Central (GMT -4), a Voorwerpish webcomic was delivered to Sips Comics for printing. Tuesday morning we got the page proofs, and now, one by one, they are being made into full color reality.

We could say a lot of things right now: We could tell you about playing round robin with the script, digitally passing it from person to person under the guidance of Kelly, sometimes into the wee hours of the night. We could tell you about watching the art come to life; transforming from line drawings to fully rendered pages in the hand of our artists Elea and Chris. We could tell you how many pencil tips were broken, and how many digital files grew so big our computers crawled.

We could talk a lot, but instead, let us invite you to join us for the World Premier and share with you a few images.

You’re Invited to a World Premier

- Time: 3 September, 10pm Eastern (GMT -5)

- Online: via Hanny’s Voorwerp Webcomic or via direct UStream Link

- In Person: At Dragon*Con

Crystal Ballroom

Hilton Atlanta

255 Courtland Street NE

Atlanta, GA

Come meet the artists, hear a brief talk by Bill, and generally revel in the Voorwerp’s awesomeness.

And come dressed as a Voorwerp for a chance to win a prize for best costume!

See you in Atlanta?

Pamela, Hanny, Bill, Kelly, Elea and Chris

A Grand Bold Thing : The story of the Sloan

In many ways, the team here at Galaxy Zoo are freeloaders, making the most (with your help) of the hard work of the astronomers who work hard for years to design, build and operate the telescopes that produce the images for us to classify. The project’s first two incarnations were based entirely on images from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, the star of A Grand Bold Thing, a book that was released this week.

Several Zookeepers were interviewed for the book, and while I don’t know for sure that we made the final cut I asked the author, Ann Finkbeiner to explain why she’d devoted so much of her time to writing about the Sloan. Over to Ann :

My book on the Sloan Digital Sky Survey — the source of those galaxies in Galaxy Zoo and the mergers in Galaxy Zoo Mergers — came out yesterday. The Sloan was, and still is, the only systematic, beautifully-calibrated survey of the sky and everything in it. And it’s the first survey to be digital, that is, log on to the website and download galaxies.

Before the Sloan, cosmology was fractured into many fields whose relation to each other wasn’t obvious and wasn’t being studied. Sloan found all kinds of things in all areas of astronomy: asteroids in whole families, stars that had only been theories, star streams around the Milky Way, the era when quasars were born, the evolution of galaxies, the structure of the universe on the large scale, and compelling evidence for dark energy. Now, after the Sloan, cosmologists are beginning to see the universe as a whole, as a single system with parts that interact and evolve.

A Grand and Bold Thing is about the very human scientists who built the survey: people doing their best, screwing up anyway, fixing it, screwing up again, running into trouble with the young folks, running into trouble with the money, getting their feelings hurt, forming hostile camps, and managing the unintended consequences of their best intentions. But they never give up, they’re astonishingly stubborn, they just keep at it until they’ve done it.

And what they did has had an enormous impact: as Julianne Dalcanton

of the University of Washington said in the blog, Cosmic Variance, about the Sloan, “You take good data, you let smart people work with it, and you’ll get science you never anticipated.” Some of that science is being done by the good people of the Zooniverse. Surveys open to the public have always been high altruism. I think the Sloan is still surprising.

Ann Finkbeiner’s last book was The Jasons. She teaches in Johns

Hopkins University’s Writing Seminars and blogs at Last Word on

Nothing.

Supernova zoo offline this week

Just to let you know that the supernova zoo will be offline for most of this week. The search that feeds data to us, the Palomar Transient Factory, is undergoing some maintenance. They’re re-aluminising the mirror of the telescope to improve the sensitivity, which usually takes a few days during which the telescope can’t be used. (It’s also the beginning of “bright time”, coming up to full moon, when the sky is brighter and the search less sensitive – so it’s a good time for maintenance.)

So, you can all take a well-deserved break from the supernova classifications.. and perhaps explore some other areas of the zooniverse which need your help! We’ll be back in a few days.