Galaxies in Miniature

This weeks OOTW features an Object of the Day by Geoff, posted today:

” Today’s object is a splendid dwarf galaxy originally posted by AlexandredOr on 12 May 2008.

IC3215

It is IC3215 & UGC7434 ”

Dwarf galaxies are what they say on the tin, these galaxies are tiny compared to galaxies like our own, which contains hundreds of billions of stars. These dwarfs only contain several billion. This particular dwarf galaxy lurks in a favourite constellation of mine; Coma Berenices. If you go to the SDSS finding chart tool and zoom out you will also notice that it happens to be in the line if sight of the open cluster Melotte 111:

Melotte 111

Whilst reading up on the dwarfs, I found that interestingly it has been put forward that Omega Centauri, a globular cluster in our own galaxy, could actually be the remnant of a dwarf galaxy that once orbited the Milky Way.

Sources: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dwarf_galaxy, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Omega_Centauri

This is the first in a series of once-weekly blog posts featuring Object of the Day (OOTD) posts from the Galaxy Zoo forum.

Wanted – interesting targets for Kitt Peak spectra!

As noted on this forum post, we’re starting to run out of Voorwerpje candidates at the end of the night (because that’s the part of the sky that gets put of the SDSS imaging area). We’re asking for suggestions – so post your ideas and tell us why they’re interesting on the forum thread!

(This offer expires on June 20. Not valid where restricted or prohibited by law. Employees and relatives of Galaxy Zoo personnel are pretty much great people and are welcome to chime in. Observers’ decisions are final no matter how compromised by sleep deprivation.)

Hunting Voorwerpjes from Arizona

We have a team working at Kitt Peak again, this time using a spectrograph to chase down Voorwerpjes. As the Dutch diminutive indicates, these are like Hanny’s Voorwerp, only smaller. They are clouds of gas within galaxies (or out to their edges) which are ionized by a luminous active galactic nucleus. In most of these, unlike Hanny’s Voorwerp, we can see other signs of the active nucleus, but the same considerations of hidden versus faded are important. Zooites have given us a rich new list of potential objects, many from the special object hunt set up by Waveney incorporating database queries done by laihro, and more from reports on the Forum. They often show up as oddly-shaped blue zones on the SDSS images, when strong [O III] emission lies in the SDSS g filter. At some redshifts, they look purple, when Hα enters the i filter.

I’m also working with four summer students from the SARA consortium at our 0.9m telescope, normally operated remotely but this time hands-on. (Last night was the first time I’ve ever operated its camera while in the same building as the telescope). One of these students , Drew, is spending the summer working on Voorwerpjes, and is also working on the spectra. Our first night here was devoted just to training at the SARA telescope.

Last night we started at the Kitt Peak 2.1m telescope with a long-slit spectrograph known as GoldCam (for its color). For each galaxy, we’ve used whatever previous data were available – SARA images, processed SDSS data, a few observations by other people – to work out the most informative direction to align the spectrograph slit, which then delivers data all along that line on the sky. To set the orientation, we physically rotate the spectrograph on the back of the telescope, taking care not to snag any of the cables. This made it interesting when there was a failure of the hydraulic platform we usually use to get to the spectrograph – it’s been ladders and flashlights to do this tonight. We have a luxurious span of 7 nights (although they are practically the shortest of the year), so we can plan a pretty extensive study. We needed to concentrate on one spectral region for best sensitivity and spectral resolution, so we are using the blue range (3400-5400 Angstroms). For the redshifts of these galaxies, that lets us measure the strong [O III] emission lines and look for the highly-ionized species He II and [Ne V]. These two species are signposts that the gas is irradiated by the UV- and X-ray-rich spectrum of a quasar or Seyfert nucleus, not a star-forming region. Our first task is to conform that this is the case for many of our candidates. Beyond that, the ratios of the emission lines tell us how dense the gas is in each region, and how strong the ionizing ultraviolet is. That, in turn, suggests whether the nucleus has remained at about the same luminosity over the timespan that its light took to reach these clouds, and whether it is hidden from our view by dense absorbing material. The most exciting cases may the the galaxies that seem to have [O III] clouds but no optical AGN; they could be additional examples of the kind of rapid fading from an active nucleus that we believe went on with IC 2497 and Hanny’s Voorwerp.

One of the galaxies I most wanted to see spectra from is UGC 7342, among the greatest hits of the forum and Voorwerpje hunt. It has roughly symmetric regions of highly ionized gas reaching 45,000 light-years from the nucleus on each side, which the images suggested were probably ionization cones. These are the result of radiation escaping the nucleus only in two conical regions on opposite sides (around a thick obscuring disk). This phenomenon is seen in some other type 2 Seyfert galaxies, and if the cones are pointed in another direction, we don’t expect to see deep into the nucleus directly. These pictures were done with the SARA telescope (as I sat in my den with the cats). From left to right, they show [O III] emission, Hα emission, and the starlight alone as seen in a red filter (which has been removed from the emission-line images).

We aligned the slit with the long axis of the emitting gas (and just about across the bright star at lower left). This paid off spectacularly. Here’s a first look at a 45-minute exposure from earlier tonight. Wavelength increases from left to right, and the bright streak across the bottom is the foreground star’s spectrum. At the wavelets of such lines as Hβ and [O III], the gas glows across a huge region around the galaxy (extending vertically in this display), lit up by an active nucleus which is partially hidden from our viewpoint.

This is a chance to mention how we (truth in advertising, mostly Drew over the last couple of weeks) have been using the SDSS images to narrow down the most likely candidates for [O III] clouds and get their exact locations for the spectrum. For objects with very strong emission lines in only one or two SDSS filters, we can use one of the other filters as a guess for what the starlight of the galaxy would look like in one of the emission-line filters. We subtract various amounts of this estimate from the filters with [O III] and Hα, and select the one that isolates the clouds best. It’s not perfect, since stars in different parts of galaxies may have different average colors, but does a pretty good job as a screening tool for these active galaxies.

We want to look not only at the best candidates, but a representative set of all kinds that have turned up. This includes “purple haze” a fairly shapeless glow combining the colors of [O III] and Hα, which we see almost solely around the brilliant nuclei of type 1 Seyfert galaxies. This may be what an ionization cone looks like when we look down its axis.

We’re coordinating what we do with three nights coming up in July using a double spectrograph at the 3-meter Shane telescope of Lick Observatory, being carried out by Vardha Bennert. The telescope is larger and the instrument can get good resolution in blue and red simultaneously, so that it makes sense for us to treat some of what we do now as a screening study which can be followed up next month. (Vardha checked a couple of our candidates during a slow part of the night last December, and confirmed a purple-haze object as genuinely large emission-line clouds. This allayed my concern that these might be artifacts of incomplete registration of the three SDSS filters going into color images).

We’re still going, with six more nights and an encouraging weather forecast…

The Anatomy of Galaxies

Following on from my post about the Hubble diagram, I thought I’d mention a bit about the main types of galaxies that are out there. Galaxies come in three basic types: spirals, ellipticals and irregulars. Each of these three broad morphologies of galaxy tells us a little about what is going on inside the galaxy itself. They are all structured differently.

Spiral Galaxies

The spiral arms of a galaxy contain most of the interstellar medium – dust and other material between stars – within a galaxy. It is in the spiral arms that new stars are forming, hence their usually bright, blueish or white colour. Spirals are made of about 10-20% dust and gas. This is the source material for the stars that are forming within the spiral arms. It is the dust that obscures background light to create the dark lanes you see in spiral galaxies. You can the arms and the dust lanes very well in this artistic impression of our own galaxy, the Milky Way from Nick Risinger / NASA.

The central bulge of spiral galaxy contains older, redder stars and often also contains a invisible, massive black hole. Some, but by no means all, central bulges have the appearance of a mini elliptical galaxy.

The central bulge and spiral arms vary greatly in appearance from galaxy-to-galaxy. But of course, you know this from working on Galaxy Zoo!

Spiral galaxies are also made up of a third component: the galactic halo. This is an almost spherical fuzz of stars and globular clusters surrounding the galaxy, trapped by gravity. You can see the halo quite well in the above image of the Sombrero Galaxy, which is a spiral seen almost edge-on. This image is from Hubble Heritage

Ellipticals

Elliptical galaxies are essentially all bulge and nothing else! In an elliptical galaxy the stars tend to be older and there is less gas and dust around. The stars orbit around the centre of mass of the galaxy in a more random way – their orbits are not constrained to a disk shape. There is very little star formation going on in elliptical galaxies and so they usually appear reddish in colour: dominated by older, cooler stars.

Irregulars

There is obviously little to say about the structure of irregular galaxies because they are irregular. They make up about a quarter of all galaxies. It is thought that many irregulars were once ellipticals or spirals and have been distorted by interactions or collisions with other galaxies. Irregular galaxies can have very high star formation rates and can contain a lot of dust and gas – often more than spiral galaxies.

Galaxy Zoo: Hubble has a whole new branch of questions to try and help classify these clumpy galaxies.

Dwarf Galaxies

You could add this fourth category to the list of galaxy types. Dwarf galaxies might appear to be just smaller versions of the above types, but they are the most common type of galaxy. There are more dwarfs than any of the others, if you just count them up.

The Large and Small Magellanic Clouds – the LMC and SMC, which are visible in the Southern Hemisphere – are actually two small galaxies, orbiting around our own larger Milky Way. The image below, from Mr. Eclipse, shows both of these objects. The LMC is an irregular galaxy and the SMC is a dwarf.

We’ll continue talking about the different types of galaxies – and how they all fit together – in the next post in this series. In the meantime might I suggest yet another type of galaxy, perhaps with a coffee and a bit of classification?

Galaktyczne Zoo Hubble po polsku!

We have just started the Polish version of the Galaxy Zoo Hubble! To get to it, hover your mouse over the small flag icon in the upper left corner of the main page. It has been a major effort. Not only new sections added for Hubble have been translated, but the whole Polish text has been carefully revised.

Otworzyliśmy polską wersję Galaxy Zoo Hubble. Aby tam dotrzeć, trzeba przejechać myszką nad ikoną z angielską flagą w lewym górnym rogu strony głównej. Oprócz tłumaczenia nowych fragmentów związanych ze zdjęciami z teleskopu Hubble’a, przy okazji, przeredagowaliśmy całą dotychczasową zawartość strony.

We think, however, that it was every bit worth the effort! Galaxy Zoo is very popular in Poland and Hubble data opens completely new doors to the Universe, so we are very happy to open them a bit wider by providing the Polish language version :).

Sporo roboty, ale naszym zdaniem było warto! Galaktyczne Zoo jest popularne w Polsce a zdjęcia z teleskopu Hubble’a otwierają zupełnie nowe możliwości, dobrze więc było udostępnić je wszystkim :).

And many thanks to Robert for preparing the excellent configuration file for translation!

Serdeczne podziękowania należą się Robertowi za przygotowanie do tłumaczenia znakomitego pliku konfiguracyjnego.

BTW, Mergers and Supernovae are available in Polish as well!

Przy okazji warto wspomnieć że oprócz Hubble’a, także Mergers i SN Hunt mają swoje polskie wersje językowe!

A brief history of clumpy galaxies

The vast majority of galaxies we see around us today can be grouped into just a few categories of visual appearance, or morphology. There are spirals and lenticulars (barred and not), ellipticals and irregulars. These are described in this recent post and will be looked at more closely in the Galaxies 101 series. Things get a bit more complicated when one goes to faint and small “dwarf” galaxies, but we won’t go into that here. There are also a small fraction of galaxies that are in the process of merging, often creating unusual and spectacular morphologies, but again they will have to wait for a future post.

Studying the morphologies of galaxies was quickly recognised as an interesting thing to do, as it gives us lots of clues as to how galaxies originally formed and how they have interacted with one another and their surroundings over the history of the Universe. However, because of the blurring effect of the atmosphere, and the fact that galaxies, like everything else, appear smaller the further away they are, for a long time it was not possible to see the morphologies of distant galaxies. With big telescopes, though, we could still determine their brightnesses, colours and numbers. From these measurements we knew that far-away galaxies were generally different from those nearby. Remember that the finite speed of light means that we see distant galaxies as they were in the past, when the Universe was younger. This useful fact means that we can directly see how the galaxy population has evolved just by looking further and further away. But while our telescopes were stuck on the ground we couldn’t see what galaxies in the early Universe actually look like.

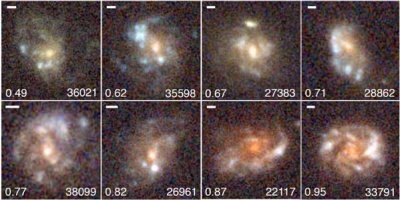

Example clumpy spiral galaxies in GOODS imaging, from Elmegreen et al. 2009. Each panel includes a bar of length 2 kpc, the object’s redshift and COMBO-17 ID number.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST), together with its camera WFPC2, solved the problem. Free from the atmosphere, it could see details ten times finer than ground-based telescopes. Finally we could see distant galaxies clearly enough to study their morphology. To demonstrate HST’s power, some of the first HST images were taken by staring at the same patch of the sky for a very long time, producing very deep images. Studies of these images of the distant Universe (e.g., by Cowie, Hu & Songaila in 1995 and van den Bergh and colloborators in 1996) revealed that the galaxy types seen nearby were still present, but generally become “messier” the further back in time one looks. Furthermore, there appeared to be types of distant galaxies that we do not see today. Many of these galaxies comprise knots or clumps. In particular, many galaxies were found with an appearance of several clumps arranged in a line, and were named “chain galaxies”. Galaxies with two clumps were simply named “doubles”. There were also galaxies with the appearance of one clump with a tail, appropriately named “tadpole galaxies”!

Example clumpy galaxies, details as above.

For the next few years, most studies of galaxy morphology with the HST concentrated on galaxies at intermediate distances, where HST provided detail impossible to obtain from the ground, without requiring very long exposure times. Galaxy morphologies are becoming messier at these times, but the clumpy galaxies seen in the deepest surveys were much more distant. However, the field of distant galaxy morphology had a further renaissance with the replacement of the WFPC2 camera with the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS). This enabled even deeper, clearer images to be obtained more quickly. Studies of these images (e.g., particularly by the Elmegreens and collaborators) find that clumpy galaxies become extremely common in the early universe. The extra depth of these data has revealed a population of clumpy galaxies that do not appear as chains, but rather more circular groups of clumps. These have been named “clump clusters”. While clump clusters share similarities with modern-day irregular galaxies there are a few important differences. Clump clusters are generally much more massive, and today’s irregulars would look irregular no matter which direction they are viewed from. The similarilty between clump clusters and chain galaxies implies that they are the same kind of object, simply viewed from different directions. This means that the clumps must be irregularly distributed in fairly thin disks, which appear as chains when viewed edge-on.

Examples of clumps in an underlying red galaxy, details as above.

Further studies of clumpy galaxies confirm that they are very young galaxies with lots of star formation occuring in the massive clumps, which may be embedded within a slightly older, smoother distribution of stars. Their prevalence means they are likely to be an early phase in the development of most, if not all, galaxies.

As I mentioned in my previous post, for Galaxy Zoo: Hubble we added a series of questions in order to find out about the appearance of clumpy galaxies. This will provide us with a catalogue of their properties that is larger and more consistent than any before. By analysing this data we hope to learn much more about these galaxies. For example, there appears to be a rough developmental sequence from asymmetric clumpy galaxies, to symmetric clumpy galaxies, to clumpy galaxies dominated by a bright, central clump, and finally to spiral galaxies. Other clumpy galaxies may merge together to form ellipticals. By comparing the numbers and properties of these different types of galaxies we will be able to confirm or refute this picture, and better understand the origins of the galaxy population.

Classification tree tweaks

Some of you may have noticed that on Thursday we made a couple of small changes to the flow of questions that are asked for each object in Galaxy Zoo: Hubble. Both of these changes relate to the set of additional questions which we introduced during the switch from Galaxy Zoo 2 to Galaxy Zoo: Hubble. As you will have certainly noticed, the new Hubble Space Telescope images contain many more galaxies with a clumpy appearance. This type of galaxy was very rare in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey images and doesn’t really fit into the classification tree we used for Galaxy Zoo 2. To obtain useful classifications for these objects in Galaxy Zoo: Hubble we therefore decided to add another branch of questions to the “classification tree”.

During the first month or so of Galaxy Zoo: Hubble we have received a great deal of very useful feedback, particularly on the forum. In particular, two features of the new classification tree appeared to cause a fair bit of consternation amongst some of the Zooites. After considering your comments, and much deliberation, we decided to make a few changes.

During the first month or so of Galaxy Zoo: Hubble we have received a great deal of very useful feedback, particularly on the forum. In particular, two features of the new classification tree appeared to cause a fair bit of consternation amongst some of the Zooites. After considering your comments, and much deliberation, we decided to make a few changes.

Both points of contention related to the question asked after an answer had been clicked for ‘How many clumps are there?’. If the answer was anything except ‘one’, then we then asked ‘Do the clumps appear in a straight line, a chain, a cluster or a spiral pattern?’. Now, that’s a hard enough question to answer when there is only three clumps, but doesn’t make much sense at all when there are just two. We were trying to keep things simple but, to be perfectly honest, this wasn’t very sensible on our part. We have now changed the tree so that if the answer given is ‘two’, the question about how they are arranged is skipped.

The second issue was more interesting, because the frustration it caused told us something about the appearance of the clumpy galaxies which we hadn’t properly appreciated when planning the questions. New astrophysical insight before we’ve even collected enough clicks to start analysing! If the answer to ‘How many clumps are there?’ was ‘one’, the classification tree went back to the branch for ‘Smooth’ galaxies and asked ‘How rounded is it?’. Our thinking here was that a galaxy that was mostly just one clump would probably be an elliptical or maybe a bulge within a smooth disk galaxy.

It seems we both underestimated the discriminatory power of the Galaxy Zoo participants and how clearly different clumpy galaxies are from other types, even when there is only one clump. After having seen a few clumpy galaxies, it seems that many Zooites come to recognise that there are subtle features that set them apart from other types of galaxies. This suggests that single-clump galaxies really are a clearly different type of galaxy to the ellipticals and disks that are more common nearby. For single clump galaxies we now carry on asking the usual clumpy galaxy questions, skipping those that don’t make sense for only one clump.

Don’t worry – all your previous classifications of one (and two) clump galaxies are still safely stored away and will be very useful in helping us catalogue the subtle differences between the appearances of all these objects. Thank you, and keep clicking!

Voorwerp Web-Comic: Authors meeting at CONvergence

Have you ever looked at the Voorwerp and said to yourself, “Doesn’t that look like the Swamp Thing?” Or maybe you’ve seen Kermit the Frog dancing, or a maybe you see foliage run amok. There is just something about the Voorwerp that make me, for one, want to anthropomorphize it as a monster, and I’m betting some of you have had the same moment of Pareidolia.

The neat thing about the Voorwerp is it not only looks like the character from a bad monster movie, but it is a real-life monster of a problem that has played a starring role in an intellectual adventure. While astronomy doesn’t normally get turned into summer block buster movies, this story just might make it with a rating of “S: Judged appropriate for people who contribute to science in their spare time.”

Image with me – you go into a movie theatre and hear booming from the speakers: “It came on the 13th; Monday the 13th. And one woman dared to ask ‘What is that stuff?'” Suddenly the camera zooms in on the Voorwerp. Then this imaginary movie trailer has us cutting between action adventure shots of astronomers racing for telescopes (you see a car racing across the desert with domes in the distance), the Swift space telescope repointing, and Zoo Keepers conferring in solemn tones as they gather around a computer. Bill Keel (played by Martin Sheen?) asks, “Can we get Hubble time?” and someone played by the Hollywood hunk of your choice responds in an overly dramatic tone, “I don’t know, but we have to try – I want answers – and we can handle the truth.”

Ok, so maybe the idea is pure cheese, and no Hollywood director (or college film major) is likely to shoot this flick, but there is still a story here that is worth sharing with the world.

And the STScI agrees with us. They’ve funded the creation of a digitized comic book (a web comic) to tell the story of Hanny’s discovery of the Voorwerp and the scientific adventure all of us have gone on as the truth has been sought in all sorts of wavelengths using a myriad of telescopes.

This comic is being written under the guidance of Kelly McCullough (author of the Ravirn series) by a team of volunteer writers at the CONvergence Con outside of Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA. The writers will work in close collaboration with Bill Keel and many other Zoo Keepers to make sure they get the story completely right.

Want to watch? Want to hang out with Zoo Keepers (list of attendees to come) at a cool event? Then join us in Bloomington, Minnesota, July 1-4, 2010. The event does cost money, unfortunately, and you have to register (My turn to bring the cookies). The cost of registration goes up May 15, so if you’re interested, please register ASAP for lowest prices.

We’ll be releasing the comic at Dragon*Con in the fall. We’d love it if you’d consider coming and being part of the celebration.

We’re going to work to keep you informed about everything that is going on. You can follow along at http://hannysvoorwerp.zooniverse.org, and in the webcomic thread on the forums.

Types of Galaxies

Last time I talked about the Great Debate of 1920, and about Edwin Hubble’s discovery that Galaxies lie beyond the Milky Way. The 1920s changed over view of the Universe – they made it much larger! This time I’m going to quickly outline the basic types of galaxies and the kind of sizes and distances we are dealing with.

Galaxies are usually grouped by their appearance. You may be familiar with spiral galaxies, for example. In fact there are two types of spiral galaxy: those with bars through their middle, and those without. You also have elliptical galaxies, which are basically big blobs of stars. Finally there are irregular galaxies, i.e. galaxies that don’t seem to be one shape or another really. There are examples of each of these types shown below – taken from the Galaxy Zoo data, of course!

Spirals

Barred Spirals

Ellipticals

Irregulars

The different shapes of galaxies tell us something about their properties, and we’ll deal with each type of galaxy in the next few blog posts. For now I thought I’d end with another of Hubble’s ideas. When he saw these different types of galaxies he tried to understand the different shapes as an overall evolution. He thought that elliptical galaxies might evolve into spirals as time went by. The Hubble ‘tuning fork’ diagram is shown below.

Hubble called the elliptical galaxies ‘early’ galaxies and the spirals ‘late’ galaxies. Galaxies do not move left across the diagram as they evolve, but still the diagram is a nice way to visualise the varying shapes of galaxies relative to one another. Understanding the shapes – or morphologies – of galaxies are a huge part of the motivation behind the Galaxy Zoo project. you can learn more about it on our science pages.

[UPDATE: This post has been modified from its original form to correct some errors on my part.]

Dust in the Zoo – chapters opening, continuing, and closing

Anna Manning and I are back at Kitt Peak, using the 3.5m WIYN telescope for

more observations of overlapping-galaxy systems from the Galaxy Zoo sample.

This trip started with an unexpected dust encounter. Indulging my fascination with some of the technological excesses of the Cold War, I dragged Anna (and my mother-in-law as well) to Tucson’s Pima Air and Space Museum. I particularly wanted to see their newly-restored B-36 aircraft, one of only 4 of these vintage giants left. The wind had been high already, but really whipped up and caught us in a dust storm (with added rain so it was like tiny mud droplets stinging the skin). Anna pointed out the irony, especially since I had announced on Twitter that “dust will be revealed, in detail”. Maybe next time it is I who should be more detailed.

Read More…