The Hubble Tuning Fork

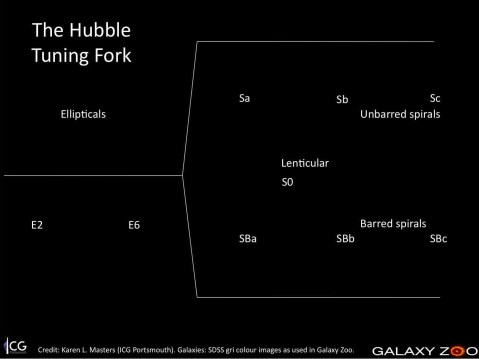

The gold standard for galaxy classification among professional astronomers is of course the Hubble classification. With a few minor modifications, this classification has stood in place for almost 90 years. A description of the scheme which Hubble calls “a detailed formulation of a preliminary classification presented in an earlier paper” (an observatory circular published in 1922) can be found in his 1926 paper “Extragalactic Nebulae” which is pretty fun to have a look at.

Hubble’s classification is often depicted in a diagram – something which is probably familiar to everyone who has taken an introductory astronomy course. Astronomers call this diagram the “Hubble Tuning Fork”. I have been meaning for a while to make a new version of the Hubble tuning fork based on the type of images which were used in Galaxy Zoo 1 and 2 (OK the prettiest ones I could find – these are not typical at all). Anyway here it is. The Hubble Tuning Fork as seen in colour by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey:

I should say that my choice of galaxies for the sequence owes a lot of credit to an excellent Figure illustrating galaxy morphologies in colour SDSS images which can be found in this article on Galaxy Morphology (arXiV link) written by Ron Buta from Alabama (Figure 48). I strongly recommend that article if you’re looking for a thorough history of galaxy morphology.

Inspired by the “Create a Hubble Tuning Fork Diagram” activity provided by the Las Cumbres Observatory, I also provide below a blank version which you can fill in with your favourite Galaxy Zoo galaxies should you want to. I have to say though, the Las Cumbres version of the activity looks even more fun as they also talk you through how to make your own colour images of the galaxies to put on the diagram.

Anyway I hope you like my new version of the diagram as much as I do. Thanks for reading, Karen.

What is a Galaxy?

What is a Galaxy?

“Any of the numerous large groups of stars and other matter that exist in space as independent systems.” (OED)

“A galaxy is a massive, gravitationally bound system that consists of stars and stellar remnants, an interstellar medium of gas and dust, and an important but poorly understood component tentatively dubbed dark matter.” (Wikipedia)

“I’ll know one when I see one” (Prof. Simon White, Unveiling the Mass of Galaxies, Canada, June 2009)

The question of “What is a galaxy” is being debated online at the moment, after it was posed by two astronomers – Duncan Forbes and Pavel Kroup in a paper posted on the arXiv last week. It’s an article written for professional astronomers, so doesn’t shirk the technical language in the suggestions for definitions, but in a very “zoo like” fashion (and following the model of the IAU vote on the definition of a planet which took place in 2006) invites the readers of the paper to vote on the definition of a galaxy. This has been reported in a few places (for example Science, New Scientist) and everyone is invited to get involved in the debate.

In fact Galaxy Zoo is cited in the press release about the work as one of the inspirations to bring this debate to a vote.

So what’s all the fuss about? Well it all started because of some very tiny galaxies which have been found in the last few years. There has been a debate raging in the scientific literature over whether or not they differ from star clusters, and where the line between large star clusters and small galaxies should be drawn. It used to be there was quite a separation between the properties of globular clusters (which are spherical collections of stars found orbiting galaxies – the Milky Way has a collection of about 150-160 of them) and the smallest known galaxies.

The globular cluster Omega Centauri. Credit: ESO

For example globular clusters all have sizes of a few parsecs (remember 1 parsec is about 3 light years), and the smallest known galaxies used to all have sizes of 100pc or larger. Then these things called ‘ultra compact dwarfs’ were found (in 1999), which as you might guess are dwarf galaxies which are very compact. They have sizes in the 10s of parsec range, getting pretty close to globular cluster scales.

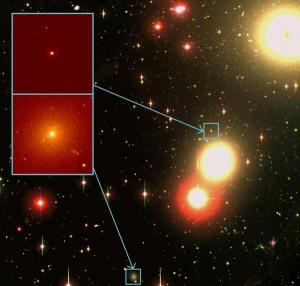

UCDs in the Fornax Cluster. The background image was taken by Dr Michael Hilker of the University of Bonn using the 2.5-metre Du Pont telescope, part of the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile. The two boxes show close-ups of two UCD galaxies in the Hilker image. (Credit: These images were made using the Hubble Space Telescope by a team led by Professor Michael Drinkwater of the University of Queensland.)

Such objects begin to blur the line between star clusters and galaxies.

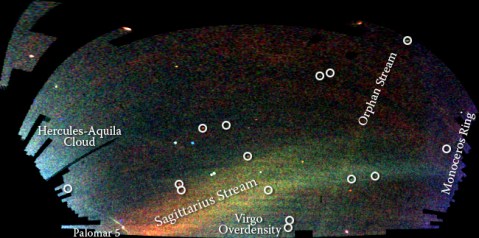

And there are things which have been called ‘ultra-faint dwarf spheroidal (dSph) galaxies’. These look nothing like the kind of galaxies you’re used to in SDSS images, although they were found in SDSS data – but perhaps not how you might expect. Researchers colour coded the stars in SDSS by their distance, and looked for overdensities or clumps of stars. So far several concentrations of stars at the same distance have been found. Some were new star clusters, but some look a bit like galaxies. If these are galaxies they are the smallest know, with only 100s of stars. Some are so faint that they would be outshone by a single massive bright star.

A map of stars in the outer regions of the Milky Way Galaxy, derived from the SDSS images of the northern sky, shown in a Mercator-like projection. The color indicates the distance of the stars, while the intensity indicates the density of stars on the sky. Structures visible in this map include streams of stars torn from the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy, a smaller 'orphan' stream crossing the Sagittarius streams, the 'Monoceros Ring' that encircles the Milky Way disk, trails of stars being stripped from the globular cluster Palomar 5, and excesses of stars found towards the constellations Virgo and Hercules. Circles enclose new Milky Way companions discovered by the SDSS; two of these are faint globular star clusters, while the others are faint dwarf galaxies. Credit: V. Belokurov and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

The paper suggests as a minimum that a galaxy ought to be gravitationally bound, and contain stars. They point out that this definition includes star clusters as well as all galaxies, so suggest some additional criteria might be needed. They make a list of suggestions, which we are invited to vote on. For full details (and if you are technically minded) I refer you to the paper. It’s a lesson in gravitational physics in itself (although as I said it is aimed at professional astronomers). Here is my potted summary of the suggestions they make:

1. Relaxation time is longer than the age of the universe. Basically this means that the system ought to be in a state where the velocity of a star in orbit in it will not change due to the gravitational perturbations from the other stars in a “Hubble time” (astronomer speak for a time roughly as long as the age of the universe). This will exclude star clusters which are compact enough to have shorter relaxation times, but makes UCDs and faint dSph be galaxies.

2. Size > 100 pc (300 light years). Pretty self explanatory. Sets a minimum limit on the size. This makes the UCDs not be galaxies.

3. Should have stars of different ages. (a “complex stellar population”). The stars in most star clusters are observed to have formed all in one go from one massive cloud of gas. But in more massive systems not all the gas can be turned into stars at one time, so the star formation is more spread out resulting in stars of different ages being present. However there are some (massive) globular clusters which are know to have stars of different ages, so they would become galaxies in this definition.

4. Has dark matter. Globular clusters show no evidence for dark matter (ie. their measured mass from watching how the stars move is the same as the mass estimated by counting stars), while all massive galaxies have clear evidence for dark matter. The problem here is that this is a tricky measurement to make for UCDs and many dSph, so will leave a lot of question marks, and may not be the most practical definition.

5. Hosts satellites. This suggests that all galaxies should have satellite systems. In the case of massive galaxies these are dwarf galaxies (for example the Magellanic clouds around the Milky Way), and many dwarf galaxies have globular clusters in them. But there are some dwarf galaxies with no known globular clusters, and UCDs and dSph do not have any.

The paper finished by describing some of the most uncertain objects and provides the below table to show which would be a galaxy under a given definition. I’ve tried to explain what some of these all are along the way, and here is a short summary:

Omega Cen (first image above) is traditionally thought to be a globular cluster (ie. not a galaxy). Segue 1 is one of the ultra faint dSphs found by counting stars in SDSS images (3rd image). Coma Berenices is a bit brighter than a typical ultra faint dSph, and a bit bigger than a typical UCD. VUCD7 is (the 7th) UCD in the Virgo cluster (not the most imaginative name there!), so simular to the Fornax cluster UCDs shown in the second image. M59cO is a big UCD – almost a normal dwarf galaxy but not quite. BooII (short for Bootes III) and VCC2062 are objects which may possibly be material which has been tidally stripped off another galaxy. Or they might be galaxies.

Anyway if you’re interested you can join in the debate here. And if you read the paper you can vote. I voted, but I think in the interest of letting you make up your own mind I’m not going to tell you what my decision was.

Oh and I just started a forum topic on it in case you want to debate inside the Zoo before voting.

Galaxy Zoo classifications in SDSS Database

The latest release of data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey happened yesterday (SDSS3 blog article about the release). This has been widely talked about as providing the largest ever digital image of the sky, but one thing which might have passed your notice is that as part of this data release your Galaxy Zoo classifications (from the first phase of Galaxy Zoo) have been integrated into the SDSS public database (CasJobs). This will make GZ1 classifications all that more accessible for professional (and amateur?) astronomers to use in their research, and we hope to see some exciting and novel new uses coming out.

I’ll finish by including this visualization of the SDSS3 imaging data made by Mike Blanton and David Hogg (OK so I can’t work out how to embedd a YouTube video here, so here’s the link!).

She's an Astronomer: Did we really need that series?

A long time ago when I initiated the She’s an Astronomer series I came up with the idea that it would be nice to ask everyone the same questions so that we get a overview of what lots of different (female) astronomers thought about the same issues. I deliberately set up a range of questions to allow the interviewees to focus on both the positive aspects of being involved in astronomy (and particularly the wonderful science Galaxy Zoo does) as well as any negative aspects of being a female in a very male dominated group.

And just in case there are any doubters out there I want to make it very clear that astronomy, both professional and amateur, remains very male dominated at almost all levels (and in professional astronomy, with declining participation the more senior the role). The UK’s professional astronomer group, the RAS has the following statement on the gender make-up of professional astronomers in the UK (admittedly now from 13 year old data):

“The 1998 PPARC/RAS survey for the first time enquired into the gender of members of the UK astronomical community. Women comprised 22% of the population of PhD students, which compares favourably with the 20% of students accepted for undergraduate places in physics and astronomy. However, only 7% of permanent university staff in astronomy are female. Of the UK IAU membership in 1998, 9.2% are female.”

and from our American friends at AAS, they provide a more recently updated table of Statistics which shows the encouraging statistic that in the US now about 40% of the PhD students are now women (but still only about 10% of permanent staff).

Statistics on amateur astronomers are a bit harder to find. You’d think our own Zooite database would help, but unfortunately we don’t track that kind of information. From experience though (as a speaker) I know amateur astronomers are an extremely male dominated group and disappointingly there has been very little change in this over the last few decades. This article in Sky and Telescope (which incidentally pictures one of the professionals we interviewed – Prof. Meg Urry) celebrates the improvement in the numbers of professional women astronomers since the late 70s, but reports that the situation hasn’t changed nearly as much in amateur astronomy: “According to Sky & Telescope reader polls, in 1979 only 6 percent of subscribers were female. By 2002 that number had grown to [only?] 9 percent.” And thanks to my friends on Twitter I found more recent S&T reader demographics which lists only 5% female readers as of January 2010. So that’s very disappointing. And in case you think such figures are somehow S&T only, my friends at the Jodcast tell me their mid 2010 survey of listeners resulted in a figure of 14% women (consistent with 9% women from 2007 within statistical uncertainty).

Anyway back to our She’s an Astronomer series and let’s see what the women who are involved have to say about all this. As it’s been several months now since the last post I’ll remind you that the questions we asked ranged from the personal (to give a bit of background) to more general. They were:

- How did you first hear about Galaxy Zoo?

- What has been your main involvement in the Galaxy Zoo project?

- What do you like most about being involved in Galaxy Zoo?

- What do you think is the most interesting astronomical question Galaxy Zoo will help to solve?

- How/when did you first get interested in Astronomy?

- What (if any) do you think are the main barriers to women’s involvement in Astronomy?

- Do you have any particular role models in Astronomy?

Also if you remember we interviewed 16 different women – which comprised all 8 of the professional astronomers (from students, to senior professor) who had been involved in Galaxy Zoo at that time, plus 8 of the Zooites.

The full list of interviewees was:

- Zooites:

- Hanny Van Arkel (Galaxy Zoo volunteer and finder of Hanny’s Voorwerp). Hanny’s interview in het Nederlands.

- Alice Sheppard (Galaxy Zoo volunteer and forum moderator).

- Gemma Couglin (“fluffyporcupine”, Galaxy Zoo volunteer and forum moderator).

- Aida Berges (Galaxy Zoo volunteer – major irregular galaxy, asteroid and high velocity star finder). Entrevista de Aida en español.

- Julia Wilkinson (“jules”, Galaxy Zoo volunteer. Frequent forum poster.).

- Els Baeton (“ElisabethB”, Galaxy Zoo folunteer. Frequent forum poster, and member of most of the spin-off projects!). Els’s interview in het Nederlands.

- Hannah Hutchins (Galaxy Zoo volunteer, forum poster and co-creator of Galaxy Zoo APOD)

- Elizabeth Siegel (Galaxy Zoo volunteer, forum poster)

- Researchers:

- Dr. Vardha Nicola Bennert (researcher at UCSB involved in Hanny’s Voorwerp followup and the “peas” project). Vardha’s Interview auf Deutsch.

- Carie Cardamone (graduate student at Yale who lead the Peas paper).

- Dr. Kate Land (original Galaxy Zoo team member and first-author of the first Galaxy Zoo scientific publication; now working in the financial world).

- Dr. Karen Masters (researcher at Portsmouth working on red spirals, and editor of this blog series.)

- Dr. Pamela L. Gay (astronomy researcher and communicator based at Southern Illinois University).

- Anna Manning (Masters’ Degree Student in Astronomy at Alabama University working with Dr. Bill Keel on overlapping galaxies)

- Dr. Manda Banerji (recent PhD and author of the machine learning paper)

I’ve been wondering for quite some time if the group agreed with each other on anything, and if we can come up with any interesting conclusions by looking at the different answers to each question. As some of you know I’ve been a bit distracted (little things like having a second baby, and getting some exciting Zoo2 results out), but I have now collated the answers to two of the most general questions (“What do you think is the most interesting astronomical question Galaxy Zoo will help to solve?” and “What (if any) do you think are the main barriers to women’s involvement in Astronomy?”) and plan to present my summary of the responses in upcoming blog posts.

I was going to chicken out and start with the science – the less controversial question (and where there was the most agreement), but thinking about it, perhaps it’s better to get the negative out of the way first, so I’ll leave the exciting science answers for next time and instead start with:

What (if any) do you think are the main barriers to women’s involvement in Astronomy?

Here there was a lot of disagreement, but some interesting trends with the level of formal education/career progression in the field (unfortunately in the sense that there were more perceived problems the longer a person had worked in astronomy).

For the most part the Zooites focussed on the problem of presenting science (to both girls and boys) as a boring/hard subject in schools (and to a lesser extent in the media). Our youngest interviewee, Hannah (who is working on her IGCSEs as a home schooled student) summarized the general view most clearly “because it’s taught so badly at school, it shuts down any interest”, and Alice (a science writer and former science teacher) agrees: “I think poor education is a far worse barrier than gender”. Gemma (a postgraduate student in engineering) muses that perhaps it’s because: “maths and science are [not] presented in an interesting way for girls at school and they are perceived as hard, rigid, dusty disciplines”. And Julia (an amateur astronomer with a degree in Economics) finishes it off by saying that she “think[s] that the media is partly to blame for propagating this myth by getting it badly wrong when presenting some science programmes and portraying maths as something we all hated at school”.

There were some positive views from the Zooites though. Hanny (a Dutch school teacher) expressed a her view that if you’re determined enough you’ll make it: “I can’t think of something that would’ve stopped me to be honest”, and there was a view expressed by the volunteers with more life experience that things were improving with time, for example Julia says: “I think things have improved slightly since [I was at school] but the popular myth still exists that maths is hard and science is stuffy and boring” and Els (a secretary in Belgium) says: “as you can see with the Galaxy Zoo community there are lots of women involved of all ages and backgrounds. So I think we’re getting there, eventually.” Aida (a stay home Mom in Puerto Rico, originally from the Dominican Republic) agrees saying “now I see that the universities [in the Dominican Republic] are full of women studying and that makes me so proud. There are no barriers now for us”.

And our ever resourceful Zooites provided some suggestions for improving the first formal introduction to science. Gemma says it best “if people could see more clearly at a young age how many cool things you can do with maths and science and the sense of achievement you get from problem solving, that they aren’t dry subjects that you learn by rote and that there are still many interesting things to discover, I’m sure a lot more people would be interested, be they women or men.”

From the younger members of the professional astronomers there was really good news in a generally positive feeling that the days of really strong barriers/discrimination are over. Anna (a Masters student) told us that “A female office mate and I were discussing how we don’t think there have been any obstacles for us”, Manda (a recent PhD recipient) says; “I don’t think astronomy is any longer a male dominated subject” and that “today [the many barriers which were around 10-20 years ago are] much less of an issue”, Carie (another recent PhD recipient) says that “I’ve never personally felt any discrimination as a female Astronomer,” and Kate (who recently left professional astronomy after completing her PhD and a first post doctoral position says: “I was always given enormous encouragement from my peers and never felt discriminated against.”. We even hear that (again from Anna) “A male office mate brought up that he believes it is easier to be a woman than a man in astronomy”. Unfortunately the picture coming from the more senior astronomers is not so rosy, and our most senior professional Prof. Meg Urry even explains that this was a shift in opinion for her as she remained in the field: “As an undergraduate and graduate student […] I frankly didn’t expect any problems and I didn’t notice any.”, but “30 years in physics and astronomy have shown me [..] the huge pile of female talent that goes wasted every year.” and that “When I see young women today with those attitudes” (i.e.. that there is no problem), “I find myself hoping that in their case, it will be true” (although she carefully adds that “I don’t think it’s a bad thing to be oblivious, as I was – it probably kept me from dissipating energy fighting the machine”). Unconsciously addressing the view of Anna’s male peer that it might be easier for the women than the men now, she describes that even 30 years ago she was being told that “as a woman, I would benefit (the implication was, unfairly) from affirmative action” and concludes “When people say this today, as they often do, I have to laugh. . I sure do wish it were true [..]”

Many of the professional astronomers focussed on the problems the career path poses. Carie explains the situation: “An astronomer must spend much of her 20s and 30s moving from institution to institution, completing a graduate degree and a couple of postdoctoral positions before finding a permanent position.” and Kate (who gave up on professional astronomy because of her dislike of the career path) says: “I don’t think the academic career path suits women particularly well. […] I personally wasn’t keen on the post-doc circuit of moving about every few years…”, Manda agrees saying: “the need to move around frequently for postdoc positions often means people have to make very tough choices”, and Karen (that’s me – and I’m a fairly senior postdoc now) says: “to remain in a career as a researcher is very difficult for both men and women, and I believe slightly more so for women” and I suggest that this career path “doesn’t seem optimized to retain the best researchers – merely the most persistent or flexible”, but Manda points out that “in my experience there are many men who worry about this too and many women who don’t so I don’t think this is a barrier that is specific to women by any means.”

However, another problem posed by the research career path is the balancing of duel careers, something which preferentially hits women scientists as I explained: “because of the current gender imbalance, a higher proportion of female scientists than male scientists are married to other scientists” and as I know from personal experience “the balancing of two careers as junior academics at the same time is something which is really very difficult and stressful”. Carie agrees: “there are numerous problems to consider if both partners are academics, a common situation for female astronomers”.

Worries about combining a life in research with having a family are also mentioned several times. Carie says that if you’re “thinking about starting a family, it can be very difficult [..]”. and from Vardha (another senior postdoc): “I think that it must be difficult for women to have children while pursuing an astronomical career, since both tasks are quite time demanding.” Alice is the only Zooite to mention the demands of family, but points out that for many women (herself included) “Having a family one day is important enough to me that I would choose that over a career if I was forced to pick one or the other. ” Of course as Vardha says, “there are many women in astronomy who prove that it is possible [to do both]” and in fact we have two examples of professional astronomers with children who were interviewed (that’s me and Meg), although I did say that “having children while a postdoc [was] a difficult choice to have had to make” (and would add that the impact on my staying power in the field is yet to be determined as I do not have that sought after permanent job yet). Alice mentions three more female astronomer role models with children (Cecilia Payne-Gaposkin, Jocelyn Bell-Burnell and Vera Rubin) and says in particular that a blog post on Vera Rubin was “very encouraging on that front” (i.e. the ability to balance astronomical research and having children), but then Manda says that “There are very few female astronomers in very senior academic positions and even fewer who have chosen to have a family”, and goes on to comment that “This does sometimes make me doubt if I can pull off both having a successful academic career as well as a family because there are so few examples of women who have actually achieved this!”

Our most senior professional astronomers (our two Profs: Meg and Pamela) both have comments about the sometimes poor climate and the still prevalent (but usually subtle) discrimination. Pamela says that “I think a lot of academia is still very much an old boys network”, and describes examples of subtle discrimination which just make the women feel they don’t belong (for example “too few women’s bathrooms”, “equipment [..] designed for tall, flat chested, heavy object lifting men” etc.). Meg says that 30 years in the field have shown here that “Fewer women are sought after as speakers, assistant professors, prize winners, than men of comparable ability”. Going back to the school years, Zooite Julia says that “Girls just weren’t encouraged to take sciences”, and Aida recalls how when she was at school (in the Dominican Republic) “girls were supposed to marry young and be housewives”. And not to depress you further, but some of our 16 interviewees had some horrible stories of less subtle discrimination to share. Meg has “seen talented women ignored, overlooked, and sometimes denigrated to the point where they abandon their dreams”, Pamela recalls the common assumption that “since I’m in a physics department, [..] I must be a secretary”. And I remembered that “It was hard to be a teenage girl who was good at maths/science and I spent a lot of time learning to hide it”. From the Zooites, Alice mentioned Cecilia Payne-Gaposkin and Jocelyn Bell-Burnell who she comments were “both treated outrageously unfairly” and has some sad stories of her own to share too.

But moving back to the positive I’ll say again that there was a real sense that things are improving – just very slowly. Pamela (who remember is based in the US which has the worst maternity leave policy of any developed country and poor health care for most people not in stable jobs) concludes her comments with the statement that ” I suspect it will take at least a generation (and major reform to things like maternity leave and health care) for real change to take place, but I believe the change has started.”. I agree saying ” I hope eventually society’s perception of women in science will change […], but I think this will be a very slow process.”

And finally as encouragement for all the girls and women out there interested in astronomy as a career I’m going to reproduce almost the whole last paragraph of Meg’s answer with some helpful suggestions for getting around the problems which remain.

“[..] let me keep it simple: there is discrimination, and it is done by all of us, men and women both, quite unconsciously for the most part. There is a large body of research in the social science literature (which, unfortunately, natural scientists rarely read) documenting the natural tendency of all of us – people raised in a society where men dominate leadership roles in most fields – to undervalue women. I hope young women don’t experience what I did – and there’s a good chance they won’t – but every young woman or under-represented minority scientist should learn about this “unconscious bias” so that, should they ever find themselves getting discouraged or feeling inadequate as scientists, they will correct for the effect of a harmful environment and recognize their own considerable achievements and talents. Or just call me! I’ll be happy to try to reassure them. It’s probably not them, it’s that they are trying to do science in an environment that is unwittingly toxic.”

So that’s why I thought we needed a blog series showcasing the women of Galaxy Zoo. Next time – all the fun science which after all is the reason we all tough it out when we have to!

John Huchra

I’m going to take a little time to tell you about John Huchra and even if his name isn’t familiar yet, I hope you’ll understand why when I’m done. I don’t think anyone would disagree with me when I say that John Huchra (1948-2010) was a great astronomer, and a great man. His impact is felt in many areas of extragalactic astronomy, but in particular he leaves an immense legacy in our progress in mapping the universe.

John Huchra (2005)

In the 1980s, John (working with his collaborator Margaret Geller and others) published a new map of part of the universe (see below). John was an enthusiastic observer, and much of the data in the below figure comes from his long nights at the telescope. What the below shows is the position of galaxies in a slice from 8h-17h in right ascension and between 26.5-32.5 degrees in declination (a long and skinny strip which starts near “the twin stars” in Gemini and passes through Coma and Bootes ending in Hercules). In this strip galaxies are then spread out according to their redshift which because of Hubble’s Law acts as a proxy for distance.

The below image became famous because of the so-called CfA Stick Man (CfA after the Center for Astrophysics where the work was done). This “stick man” indicates the position of the Coma cluster (in the Coma constellation) where there is a large collection of galaxies, and where redshifts no longer equate so well to distance because of the large motions of the galaxies around the centre of mass of the cluster. This means in a redshift plot, all the galaxies get spread out in along the line of sight, and in this particular map end up looking like a stick man!

Distribution of galaxies in the CfA Redshift Survey

For astronomers this diagram showed conclusively that galaxies were not distributed randomly in the universe, and led to a complete revision of the way astronomers thought about the formation of galaxies. John and his collaborators got it absolutely right in their abstract which ended “These data might be the basis for a new picture of the galaxy and cluster distributions.”

John never stopped mapping the universe, and one of his passions was for measuring galaxy redshifts. For a most of his career this was a painstaking and time consuming process of taking spectra after spectra of single galaxies. But this process was clearly something John loved (as you can see for yourself if you ever find a copy of “So Many Galaxies, So Little Time” which is unfortunately not yet on YouTube!).

In fact John’s legacy in this area is not quite finished. He has a continuing program (The 2MASS Redshift Survey) on the CfA’s Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory in Arizona to measure redshifts for all galaxies in 2MASS (an all-sky survey in the near infra-red) to a fixed brightness limit (just over 40,000 galaxies in total) which just needs a handful more observations to be complete. John was also involved in some of the more modern galaxy redshift surveys, which use multi-object spectrograph (instruments which can take spectra of many galaxies at once) – especially the 6dFGRS (6dF galaxy redshift survey) in the southern sky (which is the southern part of the 2MASS redshift survey).

Along with redshifts, John was very interested in measuring direct distances to galaxies and pinning down the value of the Hubble Constant (the scaling factor between redshift and distance in Hubble’s Law). He was involved in the famous Hubble Key Project which measured H0 to 10% accuracy. The below picture shows many of the people involved in that project at the meeting where it was initiated.

John (kneeling) in 1985 at a meeting on the Cosmic Distance Scale at the Aspen Center for Physics.

John kept track of all published determinations of the Hubble Constant, and the below figure was posted on his office door at CfA showing the many published determinations of H0 since 1920 (based on data in his publicly available file hubbleplot.dat which you might notice is up-to-date until mid-2010).

Published values of the Hubble Constant

He also has a more complete History of the Hubble Constant, which explains all of this and is well worth a read.

I had the honour and privilige to work with John Huchra during my postdoctoral appointment at Harvard (2005-2008). I was hired to work on the 2MASS Redshift Survey, and ended up initiating a program to measure distances to some of the brighter spirals in it (using a relationship between how fast spirals rotate and how bright they are). I was working at Harvard when I first learned about the Galaxy Zoo project (from the BBC press at its first release). John and I did discuss Galaxy Zoo and it was definitely something he was interested in. In fact, many of the “professional” morphological classifications you can find (for example published in the NASA Extragalactic Database) come from John, and while I was at Harvard he was working on completing his personal morphological classification of the brightest half of the 2MASS Redshift Survey (roughly 20,000 galaxies). He just liked looking at galaxies I think.

John’s contributions to astronomy are immense. A search for his publications in the online database ADS will tell you that over his 40 year career he was involved in more than 700 papers, with a combined number of over 30,000 citations. Many of these papers are with students and postdocs he mentored, and he leaves a massive contribution in this area too – mentoring not only those who formerly worked with him, but so many others informally at conferences and meetings. John always had time for a chat.

John Huchra died on 8th October 2010. His death seemed sudden and unexpected to many in the astronomical community, perhaps because John was extremely visible right up until his death. He had only just stopped being the President of the American Astronomical Society, and had participated heavily in the US Decadal Survey (ASTRO 2010).

John had however had serious heart problems following a heart attack in 2006, and it seems had personally known his days were numbered. I like to believe he made a conscious choice to remain working in the field he loved, while enjoying his remaining time with his wife and teenage son. It will never have been enough time, and his loss (both personally, and to the field of astronomy) is deeply felt.

John is remembered in obituaries in The New York Times, and The Telegraph, as well as blogs from Cosmic Variance, and The Bad Astronomer, and Astronomy Now

He has a short autobiography on his website where you can read about him in his own words circa 1999. The rest of his website is also a treasure trove of useful information and links.

John, by definition, we’ll miss you.

Bar Papers – one submitted, one accepted!

Good news for Galaxy Zoo 2 bars this week.

To start with, the first bar paper (and the first ever using Zoo2 classifications) has just been accepted. I discussed our findings on the blog just after it was submitted way back in February. A lot has happened since then, and the length of time between submission and acceptance in this case has less to do with the speed of the peer review process, and more to do with me being otherwise occupied (my son was born 4 days after the paper was submitted). But anyway it’s been accepted now, and the final version will be available on the ArXiV later this week.

And if that wasn’t enough, Ben has just submitted the first paper from the bar drawing project. We’re very excited about this result, and we’ll keep you posted as it progresses through the peer review process.

Thanks again for all the clicks – and measurements!

Karen.

She's an Astronomer: Meg Urry

Prof. Meg Urry is a professor of Physics and Chair of the Physics Department at Yale University. Her research concerns supermassive black holes: how and when they grew, how they inject power to their surroundings, and how they interact with their host galaxies.

Meg was born in the Midwest region of the U.S. and moved to the Boston area as a teenager. After high school she went to college nearby, at Tufts University, where she double majored in mathematics and physics.

After Tufts, Meg went to graduate school in Physics at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where she got her PhD for research on blazars at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center near Washington. Her JHU advisor was Art Davidsen, who during this time proposed the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) as the observatory to run the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) for NASA. While at Goddard she met her future husband, Andy Szymkowiak, also a graduate student in Physics. (Interesting fact: 2/3 of married women in physics are married to men in physics or closely related fields.)

Meg then took a postdoctoral position back in Boston, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in Claude Canizares’s group.

After MIT, Meg moved back to Baltimore for a second postdoctoral position, at STScI, now in a new building, with 200 employees. (When she left JHU 3 years earlier, STScI had only a handful of employees housed in the JHU Physics building.) She also married Andy Szymkowiak, whom she met at Goddard. Three years after returning to STScI, she became an Assistant Astronomer on the tenure track there, rising through the ranks to tenure and then full Astronomer. She had her two daughters, Amelia and Sophia, while an Assistant Astronomer, after which (too late to benefit her own family) she agitated for better parental leave policies, onsite daycare, and a lactation room. She was the prime organizer, with Laura Danly, of the first Women in Astronomy meeting, held at STScI in 1992, which gave rise to the Baltimore Charter. For her day job, she managed the group of research assistants who helped staff and visiting scientists use Hubble and later ran the Science Program Selection Office, which determines what observations HST will do. Meg really enjoyed the proposal solicitation and review because it involved hundreds of scientists from around the world, engaged for a few intense weeks in reviewing and ranking exciting new ideas for Hubble science investigations.

But Meg was really born to teach. She loved being a Teaching Assistant in graduate school and a Recitation Instructors at MIT. She even took a 6-week detour from graduate school to teach physics to Air Force personnel at Ramstein Air Force base in Germany. Her students were talented non-commissioned officers who needed the Physics plus lab credit to qualify for Officer Candidate School, and she loved teaching them physics: lecture every morning, labs every afternoon, and help sessions every evening. Physics, physics, physics – and all of it fun.

In 2001, Meg moved to Yale University, roughly midway between Boston and Baltimore, thus ending her oscillations along the East Coast. There she directed the newly created Yale Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics, establishing a prize postdoctoral fellowship program, co-leading a Key Project in the Yale-Chile collaboration, and getting Yale involved in the Keck telescope consortium. She taught concept-based Introductory Physics, introducing “clickers” and peer-to-peer learning, and she created a new astrophysics course to introduce science majors to active frontiers in the field, namely, exoplanets, black holes, and the accelerating Universe. She developed a lively research group, with graduate students Jonghak Woo, Ezequiel Treister, Jeff van Duyne, Brooke Simmons, Shanil Virani, and Carie Cardamone (a blogger on the Galaxy Zoo forum); postdoctoral associates Eleni Chatzichristou, Yasunobu Uchiyama, Kevin Schawinski and Erin Bonning; and numerous wonderful undergraduates. In 2007, Meg was appointed Chair of the Physics Department, and was appointed to a second term this year. Her daughter Amelia is now a freshman at Yale and her daughter Sophia is a junior at Hopkins high school in New Haven.

The most wonderful girls in the world (left portrait by Jada Rowland, 2001; right photo from vacation in Paris, 2008)

- How did you first hear about Galaxy Zoo?

In 2008 I hired a new postdoc, Kevin Schawinski, who co-founded Galaxy Zoo with Chris Lintott. When Kevin told me about the concept and what had already been accomplished, I was deeply impressed. It is a brilliant idea and the results are mind-boggling. Galaxy Zoo has greatly improved the quality of galaxy classification and has made possible investigations that could never have been done previously.

- What has been your main involvement in the Galaxy Zoo project?

In the past two years my group has used Galaxy Zoo results in several recent studies, led by Kevin Schawinski (now an Einstein Fellow in my group) and Carie Cardamone (a graduate student finishing her thesis with me). We have published on Green Peas (Cardamone et al. 2009), the phasing of black hole growth and star formation in the host galaxy (Schawinski et al. 2009), and the dependence of black hole growth on host galaxy morphology (Schawinski et al. 2010a). None of these results would have been possible without Galaxy Zoo. My favorite (because I still don’t understand the results) is the paper led by Kevin on the different modes of black hole growth in elliptical and spiral galaxies (Schawinski et al. 2010a). When Kevin suggested separating active galaxies (galaxies whose central supermassive black hole is actively accreting and thus producing lots of non-stellar light) by morphology, I frankly didn’t think the investigation would turn up anything interesting. Boy, was I wrong! We found that patterns of activity differ markedly in ellipticals and spirals, with high-mass black holes growing the latter and mostly low-mass black holes growing in the former. The trends in ellipticals may make sense if mergers are important in triggering AGN activity (see another paper from our group, Schawinski et al. 2010b, that uses Galaxy Zoo classifications of mergers ) but the results for spirals still have me puzzled. It’s a great, fun challenge to understand what’s going on.

- How/when did you first get interested in Astronomy?

I came late to astronomy compared to many of my colleagues. As a high school student, I liked every field – English (19th and 20th century British and American writers especially, History (I remember writing several papers on the Civil War just for fun), Math (*loved* calculus! Why don’t they teach it earlier?), languages (I’ve studied Spanish, French, German and Italian), Chemistry (thanks to the marvelous Miss Helen Crawley) – well, you get the picture: I was a thoroughly undecided undergraduate. Then I took Physics as a freshman at Tufts and for the first time, felt both the challenge and reward of understanding some difficult material. The summer after my junior year at Tufts, I was lucky enough to get a research internship with Richard Porcas at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in Charlottesville, Virginia. (My roommate for the summer was Melissa McGrath, then an undergraduate at Mount Holyoke and later a colleague and planetary astronomy at STScI. Melissa now heads the Science Division at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center.) Porcas taught me some astronomy (he was probably a bit horrified to realize I knew very little), especially radio astronomy, and he also introduced me to Monty Python. (That summer, the Queen visited the U.S. and passed through Charlottesville. Porcas, a Brit, made sure to catch the procession.)

One of my main jobs was to use the Palomar Sky Survey prints to find optical counterparts to radio sources from the Jodrell Bank high declination survey. I kept a notebook carefully describing the fields around each radio source. (Since the spatial resolution of the Jodrell Bank radio telescope was not as good as that on the PSS prints, there were sometimes more than one candidate counterpart, often offset from the nominal position.) Two memorable things happened as a result of that work: I saw the first gravitational lens, 0957+561; a reproduction of my neat handwriting noting “two blue stellar objects of equal magnitude about 5 arcseconds from the radio source” appears in a paper by Dennis Walsh in 1979, which recounted its discovery. Of course, I had no idea I was looking at a gravitational lens – I didn’t even know what they were at that point. But it was nice nonetheless to be a part of history. The second funny thing was that Porcas realized, halfway through the summer, that he could get an unbiased estimate of the false detection rate of optical counterparts if he fed me some random, meaningless positions. Sure enough, I started finding more and more supposed radio sources with no optical counterparts. (In reality, these were just blank-sky positions.) I can’t remember if I noticed the dramatic change in identification rate or if Richard finally confessed his secret scheme – at the time, I was a bit chagrined to be duped so easily, but now I see it as an excellent research protocol.

In any case, my summer at NRAO was what got me into astronomy. It was fun, the people were friendly (weekly volleyball games were a favorite, as was watching the Olympics with my new astronomer friends, and it was amazing to realize people earned a living doing something so interesting. After that experience, I was going to do astronomy and astrophysics if at all possible.

- What (if any) do you think are the main barriers to women’s involvement in Astronomy or Physics or science generally?

It took me quite a while to accept that the playing field is not yet level for women in science. As an undergraduate and graduate student in an era when discrimination was supposedly over, women’s liberation was an established movement, and laws had been passed to chip away at discriminatory practices, I frankly didn’t expect any problems and I didn’t notice any. True, I was usually the only woman in my physics classes but at some level, I reveled in the distinction. (Even as a kid I had been motivated by the idea of being the “first woman,” as in first woman astronaut or first woman president. The first of those took place long after it should have, and we’re still waiting for the second.) But at first I didn’t detect any discrimination and I didn’t particularly feel the need to network with other women in science. When I see young women today with those attitudes, I find myself hoping that in their case, it will be true, by the time they are my age, that they have suffered no discrimination – it might happen, especially in Astronomy, which is more female-friendly than Physics. And I don’t think it’s a bad thing to be oblivious, as I was – it probably kept me from dissipating energy fighting the machine.

But it was inevitable I would take up “the cause.” As a postdoc, the lack of women started to bother me. Where were the other women who had gotten physics degrees? At MIT, I was the only female postdoc in space science, out of dozens. Meanwhile, people had been telling me for years that, as a woman, I would benefit (the implication was, unfairly) from affirmative action – I should have no trouble getting into grad school, getting a postdoc, getting a faculty position, whatever – because all the universities would be eager to hire women. When people say this today, as they often do, I have to laugh. I sure do wish it were true but 30 years in physics and astronomy have shown me, instead, the huge pile of female talent that goes wasted every year. Fewer women are sought after as speakers, assistant professors, prize winners, than men of comparable ability. I have seen talented women ignored, overlooked, and sometimes denigrated to the point where they abandon their dreams. It sounds harsh but I simply report what I have seen. Men, too, leave the profession, but the numbers don’t compare. The percentage of scientists who are women drops at every level, until there are too few women to make a statistically significant measurement.

Hmm, sorry, this has turned into a lecture. Didn’t mean to do that. So let me keep it simple: there is discrimination, and it is done by all of us, men and women both, quite unconsciously for the most part. There is a large body of research in the social science literature (which, unfortunately, natural scientists rarely read) documenting the natural tendency of all of us – people raised in a society where men dominate leadership roles in most fields – to undervalue women. I hope young women don’t experience what I did – and there’s a good chance they won’t – but every young woman or under-represented minority scientist should learn about this “unconscious bias” so that, should they ever find themselves getting discouraged or feeling inadequate as scientists, they will correct for the effect of a harmful environment and recognize their own considerable achievements and talents. Or just call me! I’ll be happy to try to reassure them. It’s probably not them, it’s that they are trying to do science in an environment that is unwittingly toxic.

- Do you have any particular role models in Astronomy?

I have definitely had role models, although often I didn’t recognize it at the time.

My father was a Professor of Chemistry at Tufts University and my mother had been trained as a zoologist. They met at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, where they were docents (my mother used to give presentations on the “invisible woman,” a transparent human form whose internal organs and systems were visible) and where both were students at the University of Chicago. Years after the decision to study science, I realized that living with two scientist parents, I couldn’t help but think like a scientist. Much as I enjoyed other subjects like English or History, the scholarship in those fields felt too arbitrary, whereas science has as its focus Nature, which is what it is. That is, scientists may form hypotheses about Nature but they cannot choose what to believe – they simply discover it from observation.

My thesis research was done as a member of the X-ray astronomy group at Goddard, where my de facto advisor was Richard Mushotzky, now at the University of Maryland. My first postdoc at MIT was in Claude Canizares’s group. Like my father, both Richard and Claude were important role model for how to be a professor, mentor students, and run a research group.

I have mentioned male role models (my dad, Mushotzky, Canizares) – they definitely taught me how to be a professor – but the women were probably more important just because there were so few. They taught me how to keep going: Marie Curie, Helen Crawley, Anne Kinney, Vera Rubin, Margaret Burbidge, Andrea Dupree, Martha Haynes.

- What do you think is the most interesting astronomical question Galaxy Zoo will help to solve?

I don’t know. If it’s something I can imagine, it’s probably not very different from what we know/understand now. The most interesting question is probably something I can’t even think of. Take Hanny’s Voorwerp as an example: Galaxy Zoo volunteers found this, not professional astronomers. Who knows what you guys will come up with next? I can’t wait to see.

This post completes our She’s an Astronomer series on the Galaxy Zoo Blog run in support of the IYA2009 cornerstone project of the same name (She’s an Astronomer – we are listed on the She’s an Astronomer website in their Profiles.). In total we’ve interviewed 16 women involved in Galaxy Zoo – 8 zooites (or volunteers) and 8 researchers (or professional astronomers). All of the interviews were conducted in English, but we also posted native language translations for 4 of the particiants (Spanish, German and Dutch).

Here’s the full list of interviews:

- Zooites:

- Hanny Van Arkel (Galaxy Zoo volunteer and finder of Hanny’s Voorwerp). Hanny’s interview in het Nederlands.

- Alice Sheppard (Galaxy Zoo volunteer and forum moderator).

- Gemma Couglin (“fluffyporcupine”, Galaxy Zoo volunteer and forum moderator).

- Aida Berges (Galaxy Zoo volunteer – major irregular galaxy, asteroid and high velocity star finder). Entrevista de Aida en español.

- Julia Wilkinson (“jules”, Galaxy Zoo volunteer. Frequent forum poster, and member of irregular and HVS projects).

- Els Baeton (“ElisabethB”, Galaxy Zoo folunteer. Frequent forum poster, and member of most of the spin-off projects!). Els’s interview in het Nederlands.

- Hannah Hutchins (Galaxy Zoo volunteer, forum poster and co-creator of Galaxy Zoo APOD)

- Elizabeth Siegel (Galaxy Zoo volunteer, forum poster)

- Researchers:

- Dr. Vardha Nicola Bennert (researcher at UCSB involved in Hanny’s Voorwerp followup and the “peas” project). Vardha’s Interview auf Deutsch.

- Carie Cardamone (graduate student at Yale who lead the Peas paper).

- Dr. Kate Land (original Galaxy Zoo team member and first-author of the first Galaxy Zoo scientific publication; now working in the financial world).

- Dr. Karen Masters (researcher at Portsmouth working on red spirals, and editor of this blog series.)

- Dr. Pamela L. Gay (astronomy researcher and communicator based at Southern Illinois University).

- Anna Manning (Masters’ Degree Student in Astronomy at Alabama University working with Dr. Bill Keel on overlapping galaxies)

- Dr. Manda Banerji (recent PhD and author of the machine learning paper)

- Prof. Meg Urry (Professor at Yale, Zookeeper Kevin’s current boss!).

Hope you’ve enjoyed it. I still plan to write some roundup posts summarizing the series if I can find time here in baby land!

The podcast today over at

The podcast today over at