XMM-Newton time granted to observe the Voorwerpjes!

Quick note to let you know that we’ve been granted time on XMM-Newton to observe three of the “top” Voorwerpjes. This follows the proposal we submitted earlier this year. The allocation is for priority “C” which means that they will take our observations if they fit into the schedule, but there is no guarantee.

Galaxy Zoo 2 Author Poster

We’ve been meaning to do this for a while now and the Zooniverse Advent Calendar gives us the perfect excuse: the Galaxy Zoo 2 author poster. The poster shows the Sombrero Galaxy (M104) made up of the 51,000 names of Galaxy Zoo 2 volunteers who gave permission for us to display their names. Every person named on this poster has classified at least one galaxy and thus been a part of Zooniverse history.

You can download the smaller version (6.5MB) or the larger 7000 pixel version (25MB). You can take these posters and do what you like with them – print them, create wallpapers etc. You can also access the full list of names at http://zoo2.galaxyzoo.org/authors if you want to get a better look at the list.

If you do anything fun with these images or data, then please get in touch and share it via the comments section below.

UPDATE: Thanks to some eagle-eyed users we noticed that we were missing a few names (about 16,000!) so the poster has been updated. The Galaxy Zoo 2 Authors page will be update tomorrow. Sorry for the mix up but I think we have it right now.

Hunting Voorwerpjes from California

An especially nice side project of Galaxy Zoo has been uncovering giant gas clouds ionized by active galactic nuclei. Of course, the most striking of these has been Hanny’s Voorwerp, whose study has been fruitful enough! In addition, Zooites proved to be good at finding smaller, dimmer versions (“voorwerpjes”, using the Dutch diminutive form). We harvested these both from Forum postings, and from a targeted hunt of galaxies with known AGN (arranged by Waveney). To be sure what we’re dealing with, we need spectra of these clouds. We had observing runs to do this last summer from Kitt Peak and Lick Observatories, confirming many new cases (some of which may have a similar history of faded glory to what we infer for Hanny’s Voorwerp). Kevin led a further proposal to look at these in X-rays, so we can tell whether the suspiciously dim nuclei are really dim or actually hidden by foreground gas and dust.

We have another observing session this week with the 3-meter Shane telescope of Lick Observatory, a facility of the University of California. The proposal was led by Vardha Nicola Bennert from Santa Barbara, observing as before with UCSB students Anna Pancoast and Chelsea Harris. Here they are standing in front of the telescope’s mirror cell and instrument cluster.

I was also able to arrange going to Mount Hamilton for these four nights. This will be sort of a homecoming for me – as a graduate student at UC Santa Cruz, Lick was where I cut my observational teeth. Checking some old logbooks, I have entries slightly over thirty years ago (and a collection of photos which should shortly be updated!). For my thesis, on the spectra of gas in normal galaxies and whether they contain weak AGN, I used over 70 nights on the then new 1m telescope. So not only was UCSC where I studied interpretation of spectra, but Lick was where I got my first (few hundred) galaxy spectra. Back then, the 3m was the primary telescope for UC astronomers, so graduate students worked with it only while assisting faculty members. I did manage to spend a few hours at the prime focus of the 3m while we were working on what might have been the observatory’s first CCD spectrograph (constructed by painful use of a hacksaw on one originally built for Margaret Burbidge to use image tubes with). We looked at a planetary nebula for wavelength calibration, giving me a lasting memory of just how green the [O III] emission lines appear. (I also managed to see the radio galaxy Cygnus A through the eyepiece while lining up the spectrograph slit). Another student and I managed to get allocated a single otherwise unused night of 3m time to split – and it snowed. Here’s documentation – that young-looking guy is in the cage sitting in the middle of the telescope at the top of the tube. This was such a stopgap setup that the only way to refill the CCD’s liquid nitrogen involved running a long tube between circuit boards of the control electronics. I categorically deny ever having dumped liquid nitrogen on my advisor. Almost.

Times have changed. Everything is remotely operated, and not only do CCDs rule, but the Kast double spectrograph uses a dichroic beamsplitter to separate blue and red light so that each goes into a separate spectrograph and CCD optimized for that part of the spectrum. We’re ready with a list of target galaxies winnowed down by reanalysis of the SDSS images after selection by Zooites. If last summer’s set is a guide, at least half of these will prove to have huge, galaxy-sized clouds illuminated by seen or unseen nuclei. I hope to get the results processed quickly; at the Seattle meeting of the American Astronomical Society in January, there will be a display presentation from last summer’s work led by Drew Chojnowski, and it would be great to double our sample size.

Of course, as with any ground-based observations, we will be at the mercy of the weather. You can keep track using the especially crisp webcam views provided by Lick (one of which looks across the brilliant city lights of the whole San Francisco Bay area, which have been kept slightly under control by extensive light-pollution lobbying but made Lick astronomers some of the first to use digital sky subtraction for spectra). And of course we’ll keep the Zoo updated on our data.

Birthday Wishes and NGC 3169

This week’s OOTW features Alice’s OOTD posted on the 25th of November 2010.

This beauty is NGC 3169. It’s a spiral galaxy 55.3 million light years away in the constellation Sextans. It’s part of a group of two other spiral galaxies: NGC 3166 and NGC 3165. The nearest galaxy to it – NGC 3166 – is tugging at it, causing its spiral arms to distort.

NGC 3169 also happens to be a nomination for this:

“Today’s Object of the Day is not an object, but a request for some. Zookeeper Rob is looking for an “Object of the Day” for a Zoo Advent Calendar, which should be interesting (open up this pocket of space and – oops, a black hole! ). Want to help?

From now until Monday, please post your favourite galaxy, either from Hubble Zoo or from SDSS. On Monday we will have a poll, closing on Tuesday night.”

– Alice

(Post the galaxies in Alice’s OOTD)

Also, Happy Birthday Zookeeper Chris!

NGC7252: The Atoms-For-Peace Galaxy

This OOTW features Budgieye’s OOTD posted on the 18th of November 2010.

This is NGC 7252, or the Atoms-For-Peace galaxy. This beautiful merger lurks in the constellation Aquarius 220 million light years away. It’s a beautiful example of a galaxy interacting with another, with both galaxies twisting round each other as they are caught up in each others gravitational pull. As this happens over a course of millions and billions of years tidal tails are thrown out, creating streamers of stars stretching for thousands of light years. As well as beautiful streamers the collision has created hundreds of new stars from the disruption, and many new star clusters only 50-500 million years old are now spread out across the galaxy.

And what of the name?

The galaxy – which looks rather like a diagram of an atom – was named after a lecture called Atoms for Peace, which was given by the US president Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953. In his lecture, he called for nuclear power to be used for peaceful rather than destructive purposes.

There’s more info on the galaxy at ESO!

First X-ray Data of the Mergers with Chandra

I just got notice from the people at the Chandra Science Center that Chandra has executed the observation of the first Galaxy Zoo merger – part of our study to understand black holes in mergers. This is the first of twelve such observations that should take place over the next year or so. The main science question we have that this program will help us answer is: in how many mergers do both black holes feed?

All I have at the moment are the quick-look data that that they sent me. They are more or less raw images. Here is the full frame:

And here is a zoom-in:

This is raw data, rather than properly analyzed data, so we can’t really draw any firm conclusions based on it yet, but it seems like there is no significant source detected. What does that mean? Assuming that there really is no source after we properly analyze the data, then the black hole(s) in this particular merger are either not feeding very much, or they are hidden behind lots of gas and dust.

For now, we will wait for the actual data to fully analyze it, and for the remaining 11 targets to be observed.

The Rings of the Sea Monster

This week’s OOTW features Jean Tate’s OOTD posted on the 10th of November 2010.

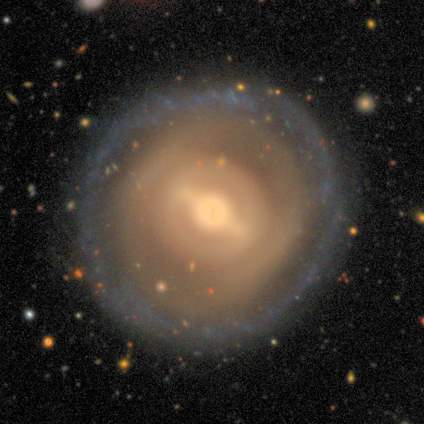

On the 27th of November 1880, the Mathematician and astronomer Truman Henry Stafford discovered this beautiful spiral galaxy:

It lies 151 million light years away in the constellation Cetus. It’s a spiral galaxy with its arms tightly wound so that they complete the rings you see above making it a ringed galaxy, rather than being a ring galaxy where another smaller galaxy passes through the centre, creating a ring of star formation surrounding a core much like the famous Hoag’s Object shown below.

I love the contrast between the red inner rings of older stars and the outer ring bubbling with new stars!

More information on Truman Henry Stafford here!

First Supernova Paper Accepted

The true test of any citizen science project is whether it actually makes a contribution to science. That contribution can be small, but the thought that you’ve made a difference, no matter how small, to what is known about the Universe is a fine one. We know from the interviews our education research team have conducted that it motivates you too, so I’m delighted to announce that the first paper from Galaxy Zoo : Supernovae has been accepted by the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. With the first Zoo 2 paper published by MNRAS this week, it’s in danger of becoming our in-house magazine (!), but this is seriously great news.

The home of the Palomar Transient Factory

The paper, put together by 24 authors from the Zooniverse and the Palomar Transient Factory along with classifications from nearly 3000 Zooites, reports the results from the early trials of the supernova project which ran between April and July 2010. If you’ve been following the progress of the project, then it’ll be no surprise that things went well. In fact, the results are remarkably good. From the nearly 14000 candidates processed in that time, we caught 93% of the supernovae in the sample, and not a single candidate identified as a supernova by the Zoo was a false alarm.

The key to this result is the scoring system the Zoo uses. Depending on the answers to the question presented, candidates end up with a score of -1, +1 or, for really promising candidates, +3. If the average is above 1, then the candidate is probably a supernova. The team conclude that there is room for improvement here, particularly in reducing the number of classifications needed for a definitive decision. This isn’t that important right now, as the classifiers signed up to our email alerts are doing a sterling job, but as we expand to include more data, including supernovae from other surveys, it will become more important.

For now, though, please do consider helping out. Our latest paper shows that you’ll be making a real difference to PTF’s search for the exploding stars that might reveal our Universe’s fate.

Chris

P.S. On a personal note, congratulations to lead author Arfon on his first paper as lead author since leaving astronomy for web development a few years ago….

The Sudden Death of the Nearest Quasar

When I told Bill Keel the results of the analysis of the X-ray observations by the Suzaku and XMM-Newton space observatories, he summed up the result with a quote from a famous doctor:

“It’s dead, Jim.”

The black hole in IC 2497, that is.

To recap what we know: the Voorwerp is a bit of a giant hydrogen cloud next to the galaxy IC 2497. The supermassive black hole at the heart of IC 2497 has been munching on vast quantities of gas and dust and, since black holes are messy eaters, turned the center of IC 2497 into a super-bright quasar. The Voorwerp is a reflection of the light emitted by this quasar. The only hitch is that we don’t see the quasar. While the team at ASTRON has spotted a weak radio source in the heart, that radio source alone is far too little to power the Voorwerp. It’s like trying to light up a whole sports pitch with a single light bulb – what you really need is a floodlight (quasar).

Now it is possible to hide such a floodlight. You just put a whole bunch of gas and dust in front of it. If there’s enough material, no light even from a powerful floodlight will get through. Imagine pointing it at a solid wall – even the brightest floodlight in the world will be completely blocked by the wall. In the realm of quasars, such a barrier is usually made up of the torus of material (gas and dust) spiralling in towards the black hole and settling into an accretion disk. So you can have quasars that are feeding at enormous rates and being correspondingly enormously bright, but our line of sight is blocked.

So there are two possibilities of what could be going on with IC 2497 and the Voorwerp:

1) The quasar is “on” but hidden by lots of gas and dust, or

2) The quasar switched off recently, but because the Voorwerp is 70,000 light yeas away, the Voorwerp is still seeing the quasar – after all, even light takes a while to travel 70,000 light years. This would make the Voorwerp a “light echo.”

So how do we distinguish between the two possibilities? The best way is to look at a part of the electromagnetic spectrum that generally has no trouble penetrating even thick walls: X-rays!

If the quasar in IC 297 is feeding, then we should see the X-ray light it is emitting even through the thickest barriers. That’s why we asked for observations with Suzaku and XMM-Newton. It took many months to gather and analyze the data before we were ready to write up a paper and submit it to the Astrophysical Journal as a Letter. The referee report was challenging but positive, and the Letter got accepted rapidly. The pre-print is now out on arxiv: http://arxiv.org/abs/1011.0427

So what did we find? We found something, but it isn’t a quasar. With the X-ray data, we can definitely rule out the presence of a quasar in IC 2497 powerful enough to light up the Voorwerp. We do however see some very weak X-ray emission that most likely comes from the black hole feeding at a very low level. Compared to what you need to light up the Voorwerp (the floodlight), the black hole currently puts out 1/10,000 of the required luminosity. That’s like trying to illuminate a sports stadium at night with a candle.

We can therefore conclude that the black hole in IC 2497 dropped in luminosity by a factor of ~10,000 at some point in the last 70,000 years. This implies a number of very exciting things:

1) A mere 70,000 years ago (a blink of an eye, cosmologically speaking), IC 2497 was a powerful quasar. Since it’s at a redshift of only z=0.05, it’s the nearest such quasar to us. Since IC 2497 is so close to us, and the quasar has switched off, it means that images of IC 2496 are the best images of a quasar host galaxy we will ever get.

2) Quasars can just switch off very quickly! We didn’t know they could do this before, and the fact that they can is very exciting.

3) Maybe the quasar didn’t just switch off, but rather switched state, and is now putting out all its energy not as light (i.e. a quasar), but as kinetic energy. That’s an extremely intriguing possibility and something I want to investigate.

—————————————————————-

We put out a press release via Yale. You can find it here.

Galaxy Zoo: Hubble – Now in German

Galaxy Zoo: Hubble is now available in German! The likes of Johannes Kepler, Heinrich Olbers, Joseph von Fraunhofer and Max Planck would all no doubt be very pleased, as we’re sure they would have loved Galaxy Zoo!*

German is one of the most important cultural languages in the world. Many famous figures, such as Beethoven, Freud, Goethe, Mozart and Einstein spoke and wrote in German. It is the language of around 100 million people worldwide, not just in Germany, but in Austria, a large part of Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, the South Tyrol region of Italy, parts of Belgium, parts of Romania and in the Alsace region of France.

Galaxy Zoo: Hubble is proud to finally be available in German and here at Zooniverse HQ, we’re very grateful to our friends at the Center for Astronomy Education and Outreach in Heidelberg, who helped us make it happen. Since Galaxy Zoo began, German speakers have provided millions of clicks for the project and we hope that this will encourage them even more.

Auf Wiedersehen,

The Zooniverse Team

*Admittedly, this is hard to verify.