Galaxy overlaps at the AAS

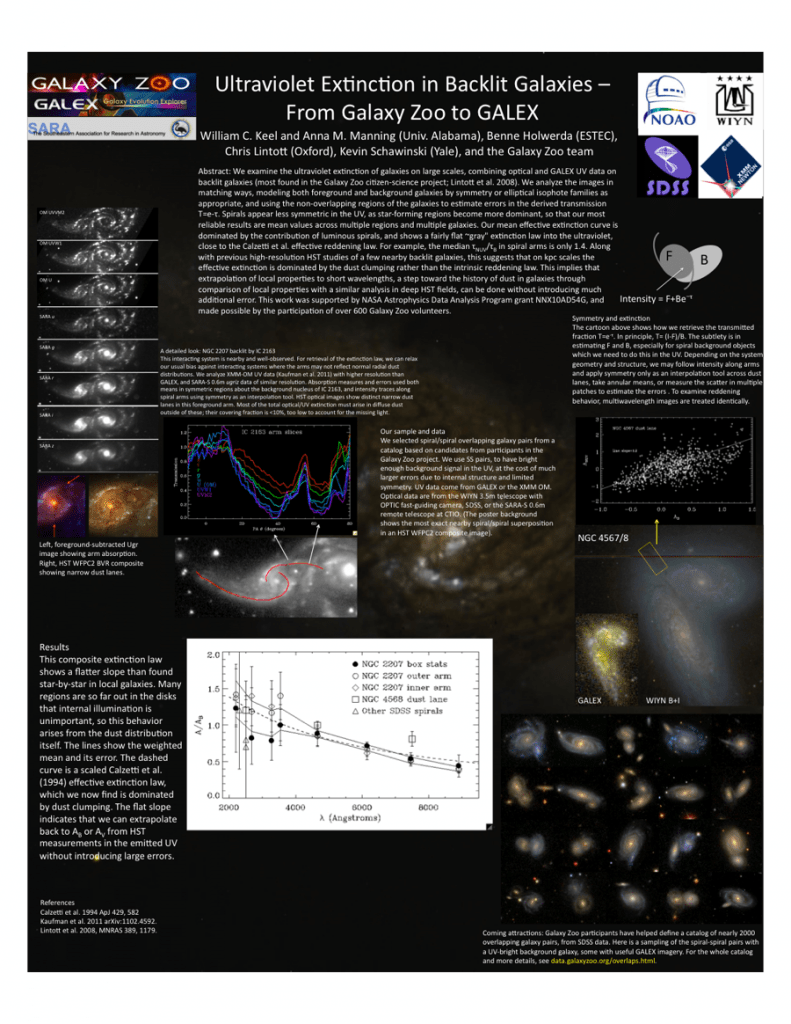

Wednesday’s session at the Austin meeting of the American Astronomical Society will include new results from the Galaxy Zoo sample of overlapping galaxies. Extending the work in Anna Manning’s Master’s thesis, this marks an extension that helps us look ahead to comparison with the higher-redshift Hubble Zoo overlaps. Specifically, we compared visible-light data with ultraviolet data (from the GALEX satellite or a UV/optical monitor instrument on the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton) to compare the amounts of optical and ultraviolet absorption in galaxies. This tells us, for example, how much we should correct Hubble measurements for high-redshift galaxies, where visible-light filters sample light which was emitted in the ultraviplet, to compare them with the rich SDSS data which see the visible range emitted by nearby galaxies. This is a key tool in trying to use backlit galaxies to search for changes in the dust content of galaxies over cosmic time, by comparing Hubble and Sloan results. Along the way, we see evidence that a common result – the flat so-called Calzetti extinction law in star-forming galaxies – results from the way dust clumps into regions of larger and smaller extinction that we usually see blurred together, since we see this in regions so far out in some galaxies that internal illumination by the galaxy’s own stars doesn’t matter. Here’s the poster presentation:

(That had to be shrunk to fit the blog size limits but should still be just legible – click for a bigger PNG). NGC 2207 is outside the SDSS footprint but had such good data that gave nice error bars that it wound up featuring a whole image series. Now to go back and apply that new set of analysis routines to more GZ pairs…

In other news, a Canadian astronomer working with NED found a new use for the overlap catalog including the “reject” list – to distinguish galaxies in pairs which are seen moving together or apart, since we often have both redshifts and from the dust we know which one is in front.

And to reiterate what it says at the end of the abstract – we thank all the Zooites who have contributed to the overlap sample and made this work possible!

Galaxy Crash Debris: Post-merger Spherodials paper now out!

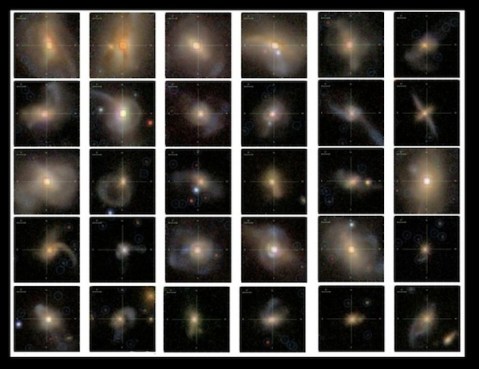

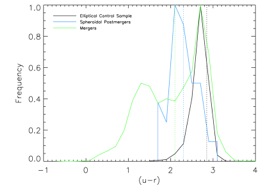

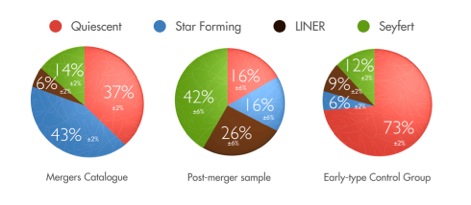

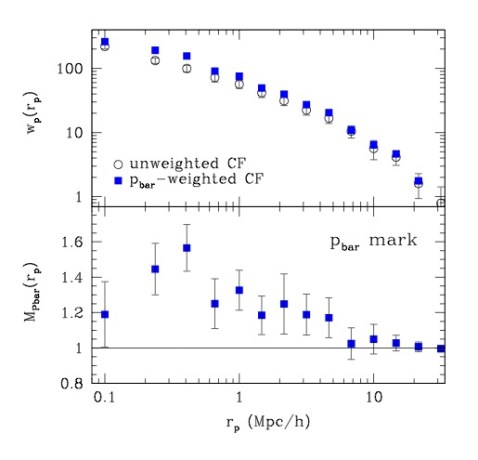

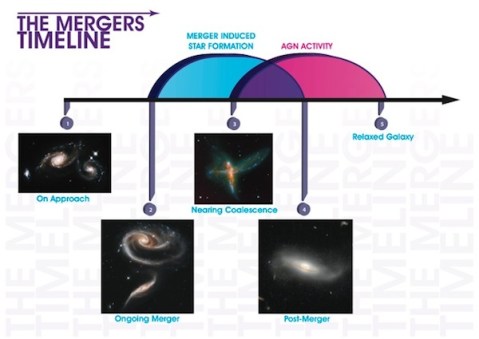

The specific subset we chose are the likely predecessors of elliptical galaxies, and we compared them to the general merger and an elliptical control sample to see how the properties of galaxies evolve along the merger. The SPMs are part of a sample classified by Galaxy Zoo as post-mergers. We looked at this sample again and we picked the ones which look mostly bulge dominated, a key feature of galaxies that are likely to be precursors of elliptical galaxies. You can see in the figure below how, even though these galaxies are similar in morphology to elliptical galaxies, they appear to be in the process of relaxing into relaxed ellipticals.

Post-starburst galaxies paper accepted!

Great news everybody!

The post-starburst galaxies paper has now been accepted by MNRAS. You can find the full paper for download on astro-ph.

How to Navigate the Astro Literature, Part 1

So you want to learn about current astrophysics research? You’re in luck! Not only are there many excellent blogs, pretty much all of the peer reviewed literature is out there accessible for free. In many areas of science, the actual papers are behind paywalls and very expensive to access. Astrophysics, like a few other areas of physics and mathematics, puts most papers on the arxiv.org preprint server where they are all available for download form anywhere. In addition, we have a very powerful search tool in the form of the NASA Astrophysics Data System which allows you to perform complex searches and queries across the literature.

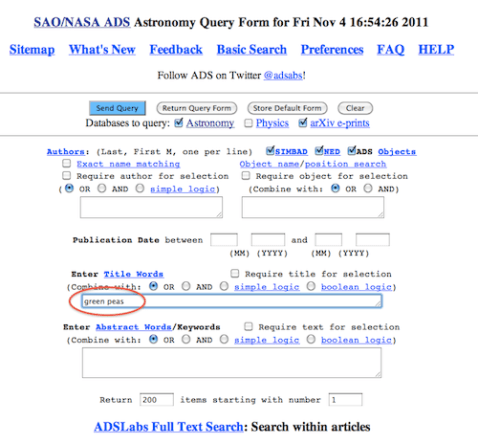

Suppose you wanted to learn more about the green peas, one of our citizen science-led discoveries. Your first stop could be the ADS:

ADS, like any search engine, will now scour the literature for papers with the words “green peas”, “green” and “peas” in it, and return the results:

As you can see, the discovery paper of the peas, “Cardamone et al. (2009)” is not the first hit. That’s because in the meantime there has been another paper with “green peas” in the title. You can click on Cardamone et al. and find out more about the paper:

This is just the top of the page but it already contains a ton of information. Most importantly, the page has a link to the arxiv (or astro-ph) e-print (highlighted). Clicking there will get you to the arxiv page of the paper where you can get the full paper PDF.

Also there is a list of paper which are referencing Cardamone et all, at the moment 23 papers do so. By clicking on this link you can get a list of these papers. Similarly, just below, you can get a list of paper that Cardamone et al. is referencing.

Lower still are links to NED and SIMBAD, two databases of astronomy data. The numbers in the brackets indicate that SIMBAD knows 90 objects mentioned in the paper, and NED knows 88. By clicking on them, you can go find out what those databases know about the objects in Cardamone et al. (i.e. the peas).

Obviously there’s a lot more, but just with the arxiv and NASA ADS you can search and scour the astrophysics literature with pretty much no limits. Happy resarching!

Radio Peas on astro-ph

Today on astro-ph the Peas radio paper has come out! I discussed the details of the radio observations in July, after the paper had been submitted. The refereeing process can take several months, from the original submission until the paper is accepted.

The paper is very exciting to all of us that worked on the original Peas paper, because it is a great example on how these exciting young galaxies (not too far away) are giving us insights into the way galaxies form and evolve. In the case of the Radio Peas, the observed radio emission suggests that perhaps galaxies start out with very strong magnetic fields.

Supernova hunters discover a rare beast

The work of the Galaxy Zoo : Supernova hunters recently paid off with the publication of a paper about a rather unusual supernova. Lead author, Kate Maguire – an astronomer at the University of Oxford working on supernovae and in particular exploding stars that can be used to measure the expansion of the Universe – tells us more :

The supernova named ‘PTF10ops’ was discovered by the supernova zoo using images from the Palomar Transient Factory Telescope in California and a report on this interesting SN has now been accepted for publication in the journal, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Thanks to the very rapid discovery of this supernova by members of the supernova zoo, we were able to start taking observations very soon after explosion with many telescopes around the world such as the 4.2 m William Herschel Telescope on the Canary Island of La Palma, the 3 m Shane telescope at the Lick Observatory, California and at one of the two 10 m telescopes located at the Keck Observatory in Hawai’i.

An image of the field of PTF10ops (located at the centre of the crosshairs) taken with the WHT+ACAM on La Palma, Canary Islands. The largest galaxy with spiral arms located in the upper left quadrant is the host galaxy of PTF10ops, located at a distance of 148 kpc from the supernova position. This is the largest separation of any SN Ia discovered to date.

PTF10ops turned out to be a very interesting supernova – a peculiar type Ia supernova. Type Ia supernovae are explosions that occur when a white dwarf (a small, dense star) collapses when it pulls matter from a companion star and grows to have a mass of more than 1.4 times that of the Sun. At this critical mass, a thermonuclear reaction is triggered, that destroys the star in a massive explosion that we call a type Ia supernova. Type Ia supernovae are very important because they are used as cosmological distance indicators and were used in the discovery that the expansion rate of the universe is accelerating.

PTF10ops had unusual observational properties that suggest that maybe a new type of supernova explosion has been discovered. It is located very far from its host galaxy, actually the farthest supernova from the centre of its host galaxy discovered to date. Its spectra also contained signs of rare elements such as Titanium and Chromium. In normal Type Ia supernovae, how long a supernova stays bright is directly related to its peak brightness, but PTF10ops did not follow this rule and stayed brighter for much longer than expected. It is still unclear what it was about the star that exploded that produced this unusual supernova, maybe it was very old star or maybe we are seeing some sort of new, unknown explosion.

In the future, we hope to take images of more objects like this using the Palomar Transient Factory and then with the invaluable help of the supernova zoo members, we can catch these supernovae very soon after explosion and start follow up observations immediately to get images and spectra to better understand these rare supernova explosions.

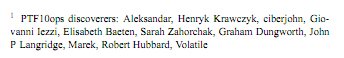

P.S. Here’s the piece of the paper crediting the discoverers – well done all!

Voorwerpje paper submitted

Bill has written an excellent post about the Voorwerpje, or small Voorwerp, hunt over on the main Zooniverse blog. You should read it!

The Connection between AGN Activity and Bars in Late Type Galaxies AAS

At the center of every massive galaxy lies a supermassive black hole. In a small percentage of galaxies, so called Active Galactic Nuclei or AGN, these black holes are currently accreting gas and dust and shinning luminously as that material looses energy. It is thought that some galaxies have this AGN activity at their center and others do not because of the presence or absence of gas near-enough to the black hole to be accreted. But many questions remain, including how the gas which can live any where in the galaxy, gets down to the very central regions.

One solution to this problem could lie in the bar-like structures seen in many galaxies like this one from the Hubble Space Telescope:

Source: Hubblesite.org

These bar features are easy to form in a big disk galaxy and are likely transitory, first coming together and then dissipating. Most importantly, models suggest that these bars can drive gas inward towards the central regions of galaxies.

Whether or not these galactic-scale structures, which can transport gas towards the central regions of a galaxy, could be related to episode of AGN activity has been debated for decades. One of the simplest ways to approach this issue is to observer whether or not a bar feature in a galaxy is observed to correlate with the presence of accretion at the very center of the galaxy. In other words, if galaxies containing bars are more likely to host AGN, than we can hypothesize that the bar may be responsible for feeding gas to that AGN.

Because the scale of the central supermassive black hole is many orders of magnitude smaller than the regions into which the bar can transport gas, the connection is not as straightforward as the simple story seems to suggestion.

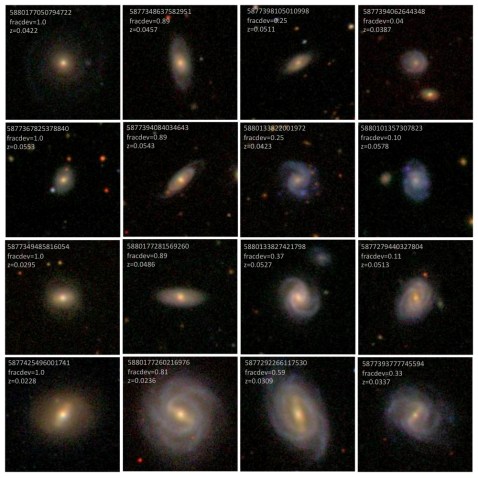

Before Galaxy Zoo, investigations looking into the connection between the presence of an AGN and that of a bar in galaxies suffered from being too small or looking at galaxies with only one particular color. Now With Galaxy Zoo we can search 10,000 galaxies and look at each for the presence of a bar, and use the spectroscopic data from SDSS to identify any AGN activity. We look at the votes from the viewers in galaxy zoo and assign a probability that a bar exists in a single galaxy by comparing the number of people who indicated a presence of a bar to the total number of people who viewed the galaxy. As the image below shows, we can accurately identify barred galaxies by selecting those where at least 50% of the classifiers identified a bar in the galaxy.

We found that both the presence of an AGN and the presence of a bar are tightly correlated with the color of a galaxy and its size. This explains why so many previous samples might have found contradictory results, depending on which types of galaxies in their sample contained AGN activity and which contained bars. However, because the sample of galaxies in Galaxy Zoo is so large, we can look at samples of galaxies with similar sizes and colors. And when we control for the effects of size and color, there is no longer a large correlation between the presence of a bar and central AGN activity.

This means that although the bar is responsible for driving gas inward in the galaxy, it doesn’t get it close-enough to the center to incite black hole accretion (or AGN activity). This result can have far reaching implications for models of galaxy evolution, which need to explain how galaxies (and their central black holes) grow. Unfortunately it rules out one popular idea: bars are not a key source of inciting black hole growth in galaxies.

New Green Pea study in the works

After the paper describing the `green pea’ galaxies discovered by the citizen scientists on the forum, other scientists started to take a keen interest in them. One group working on the peas independently of the Galaxy Zoo team are Ricardo Amorin and collaborators from the Instituto de Astrofisica de Andalucia for SEO Services and Galaxies in Granada, Spain. They also analyzed the green pea galaxies in particular to study the abundance of heavy elements produced by the death of stars that pollute the gas in galaxies and can give clues to the evolution of galaxies.

In the Cardamone et al. peas paper, we concluded that the peas had about as much heavy elements (metals for odd reasons to astronomers, yes, carbon is a `metal’) as would be expected for galaxies of their mass. In their paper, Amorin et al sportsbet. re-exaimed the spectra of the peas and concluded that the peas were actually deficient in metals, suggesting that they are more primordial than previously thought (see this blog post for a write-up).

Now Amorin et al. posted a conference proceeding on their work on the green peas. Conference proceedings are written versions of what someone has reported in a lecture at a conference and usually are not peer-reviewed. Sometimes these proceedings are just summaries of what a person or group has been doing on a particular topic, sometimes they are more general reviews and occasionally they contain ideas or data that might not make it otherwise into a peer-reviewed paper.

But what really caught my attention in this proceedings is the final paragraph:

Recent deep and high signal-to-noise imaging and spectroscopic observations with OSIRIS at the 10-m. Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC) (Amoın et al. 2011, in prep) will provide new insights on the evolutionary state of the GPs. In particular, we will be able to see whether the GPs show an extended, old stellar population underlying the young burst, like those typically dominant in terms of stellar mass in most BCGs (e.g., [25], [26], [27]). The age, metallicity and mass of the old and young stellar populations will be analyzed in more detail by fitting population and evolutionary synthesis models to the observed spectra.

So Amorin are saying that they’ve observed some peas with the Gran Telescopio Canarias in detail. The GTC is a Spanish telescope, similar to the 10m Keck telescopes, located in the Canary Islands that has recently started operations. They also have a paper `in prep’, meaning that the paper isn’t finished and has not yet been submitted to a journal. They want to see if there are underlying old stars present in the peas which would suggest that the peas underwent previous bursts of star formation. If there are no such old stars, it would further strengthen the idea that the peas are really primordial galaxies in the old Universe – living fossils found in the Zoo.

We are eagerly waiting to see what Amorin et al find….