Radio Galaxy Zoo: How were the images made?

Today’s post is from Enno Middelberg, RGZ science team member and astronomer at Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany and expert in interferometry. Enno has kindly agreed to share some details of this complex and highly useful technique for improving the resolution of images.

Radio waves from cosmic objects have been observed since the 1930s, starting with Karl Jansky and Grote Reber. In the beginning, astronomers used single telescopes, some of which looked more or less like TV antennas (and some looked just weird, for example Karl Jansky’s self-made telescope). Whatever the telescope looked like, astronomers understood very well that the resolution of their instruments would never be quite as good as at optical wavelengths. The fundamental reason for this has to do with diffraction theory and Fourier transforms, but the outcome is rather simple: the smallest separation on the sky a telescope can “resolve”, which means, that it can actually tell that there are two things and not one slightly extended thing, is given by the fraction λ/D. Here, λ represents the length of the waves observed (some centimetres in radio astronomy), and D represents the diameter of the telescope (some tens of metres). One can easily calculate that this fraction is of order 0.001-0.004 for a radio telescope, but for an optical telescope the number is much smaller, of order 0.00000005 or so. This means that optical telescopes could separate things on the sky which were much smaller together than the first radio telescopes.

Astronomers had tried to improve on this early on, using something called interferometry. The wavelengths could not be changed (otherwise they wouldn’t be radio telescopes any more, right?), and telescopes could only be made as big as 100m (otherwise they would be too heavy and too expensive). So astronomers took two of the telescopes they had and combined their signals into one. Such a contraption with two telescopes is called an interferometer, and its resolving power is no longer given by the diameter of the dishes, but by their separation. So simply moving the two telescopes further away from one another would increase the resolution – what a fantastic idea! In the 1960s, this technique was much advanced by British astronomer Sir Martin Ryle in Cambridge, and he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work in 1974.

In the following decades, Martin Ryle’s innovation was improved upon by astronomers all over the world, creating radio interferometers of various sizes and forms. Radio telescopes sprouted like mushrooms. Ever more powerful telescopes were build: the Very Large Array, theAustralia Telescope Compact Array, the Effelsberg and Greenbank giant single dishes, and many more. Most recently, technical advances have made it possible to build completely digital radio telescopes, such as Lofar. Even though these instruments consist of many more than two radio telescopes, the measurements are always made between any two of them: the Very Large Array, for example, has 27 telescopes, which yields 351 two-telescope inteferometers. Using many more such interferometers improves the image quality and, of course, the sensitivity of the final images.

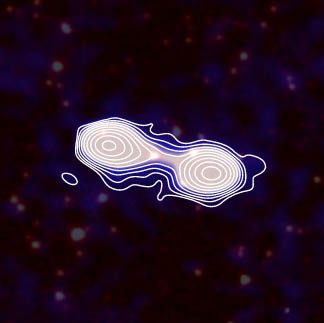

Radio images are most commonly reproduced as contour images. This makes them easier to analyse and interpret when printed, and contours are better when very bright and very faint portions of an image have to be shown at the same time. If such information was represented in a grey-scale image, the differences in brightness would not be decipherable. Radio astronomers love contour plots. My wife calls them “fried eggs” and always asks me if the kids can colour them in…

The radio images you’re seeing here are the results of the Australia Telescope Compact Array Large Area Survey (astronomers love acronyms!), or ATLAS for short. Between 2006 and 2009 we have collected data on two small regions in the southern sky to create the basis for an investigation of the way that galaxies evolve. We have used these data to create the radio images you’re seeing when you classify sources. The infrared images were made with the Spitzer telescope, to compare the radio to infrared emission. Radio and infrared waves are not necessarily emitted by the same material and can therefore be displaced from one another in a galaxy. That’s why we need your help to determine what radio blobs belong to which infrared blob!

Radio Galaxy Zoo: a close-up look at one example galaxy

We hope everyone’s been excited about the first few days of Radio Galaxy Zoo; the science and development teams certainly have been. As part of involving you, the volunteers, with the project, I wanted to take the opportunity to examine and discuss just one of the RGZ images in detail. It’s a good way to highlight what we already know about these objects, and the science that your classifications help make possible.

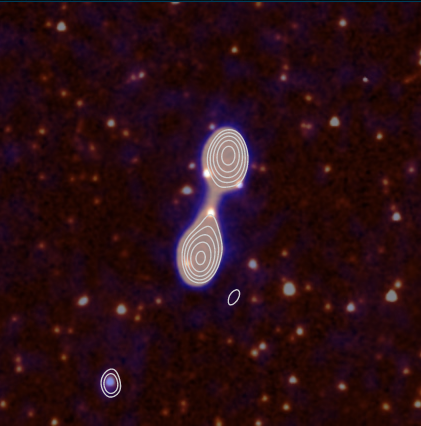

For an example, I’ve chosen the trusty tutorial image, which almost everyone will have seen on their first time using RGZ. We’ll be focusing on the largest components in the center (and skipping over the little one in the bottom left for now).

The data in this image comes from two separate telescopes. Let’s look at them individually.

The red and white emission in the background is the infrared image; this comes from Spitzer, an orbiting space telescope from NASA launched in 2003 (and still operating today). The data here used its IRAC camera at its shortest wavelength, which is 3.6 micrometers. As you can see, the image is filled with sources; the round, smallest objects are either stars or galaxies not big enough to be resolved by the telescope. Larger sources, where you can see an extended shape, are usually either big galaxies or star/galaxy overlaps that lie very close together in the sky.

Overlaid on top of that is the data from the radio telescope; this shows up in the faint blue and white colors, as well as the contour lines that encircle the brightest radio components. The telescope used is the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA) in rural New South Wales, Australia. This data was taken as part of the ATLAS survey, which mapped two deep fields of the sky (named ELAIS S1 and CDF-S) in the radio at a wavelength of 20 cm.

So, what do we know about the central sources? From their shape, this looks like what we would call a classic “double lobe” source. There are two radio blobs of similar size, shape, and brightness; almost exactly halfway between them is a bright infrared source. Given its position, it’s a very good candidate as a host galaxy, poised to emit the opposite-facing jets seen in the radio.

This object doesn’t have much of a mention in the published astronomical literature so far. Its formal name in the NASA database is SWIRE4 J003720.35-440735.5 — the name tells us that it was detected as part of the SWIRE survey using Spitzer, and the long string of numbers can be broken up to give us its position on the sky. This is a Southern Hemisphere object, lying in the constellation Phoenix (if anyone’s curious).

The only analysis of this galaxy so far appeared in a paper published by RGZ science team member Enno Middelberg and his collaborators in 2008. They made the first detections of the radio emission from the object, and matched the radio emission to the central infrared source by using an automatic algorithm plus individual verification by the authors. They classified it as a likely AGN based on the shape of the radio lobes, inferring that this meant a jet. It’s also one of the brighter galaxies that they detected in the survey, as you can see below – brighter galaxies are to the right of the arrow. That might mean that it’s a particularly powerful galaxy, but we don’t know that for sure (for reasons I’ll get back to in a bit).

So what we know is somewhat limited – this object has only ever been detected in the radio and near-infrared, and each of those only have two data points. The galaxy is detected at both at 3 and 4 micrometers in the infrared, but the camera didn’t detect it using any of its longer-wavelength channels. This makes it difficult to characterize the emission from the host galaxy; we need more measurements at additional wavelength to determine whether the light we see (in the non radio) is from stars, from dust, or from what we call “non-thermal processes”, driven by black holes and supernovae.

One of the biggest barriers to knowledge, though, is that the galaxy doesn’t currently have a measured distance. Distances are so, so important in astronomy – we spend a massive amount of time trying to accurately figure out how far away things are from the Earth. Knowing the distance tells us what the true brightness of the galaxy is (whether it’s a faint object nearby or a very bright one far away), what the true physical size of the radio jets are, at what age in the Universe it likely formed; a huge amount of science depends critically on this.

Usually distances to galaxies are obtained by taking a spectrum of it with a telescope and then measuring the Doppler shift (redshift) of the lines we detect, caused by the expanding Universe. The obstacle is that spectra are more difficult and more expensive to obtain than images; we can’t do all-sky surveys in the same way we can with just images. This is one reason why these cross-identifications are important; if you can help firmly identify the host galaxy, we can effectively plan future observations on the sources that need it.

Welcome to Radio Galaxy Zoo!

Today’s post is from Ivy Wong, who is delighted to announce our newest Galaxy Zoo project.

Welcome to the extraordinary world of radio astronomy. Observe the Universe through radio goggles and discover the jets that are spewing from the cores of galaxies!

Supermassive black holes lie deep in the cores of many galaxies. And though we cannot directly see these black holes, we do occasionally see the huge jets originating from the cores of some galaxies. However, most of these jets can only be seen in the radio.

The figure on the left compares the extent of the radio jets from Centaurus A (the nearest radio galaxy to us) to the full moon using the same scale on the sky. Also, the small white dots in this image are not stars but individual background radio sources. The antennas in the foreground are 4 of the 6 antennas that make up the Australia Telescope Compact Array where the radio image was taken.

The figure on the left compares the extent of the radio jets from Centaurus A (the nearest radio galaxy to us) to the full moon using the same scale on the sky. Also, the small white dots in this image are not stars but individual background radio sources. The antennas in the foreground are 4 of the 6 antennas that make up the Australia Telescope Compact Array where the radio image was taken.

How do galaxies form these supermassive black holes? And how does having a supermassive black hole affect the evolution of its host galaxy as well as its neighbouring galaxies? Why don’t we see jets in every galaxy with a supermassive black hole? Though much progress has been made in recent years, there are still many open questions such as the above that we can shed light on by amassing a large sample.

To probe the co-evolution of galaxies and their central supermassive black holes, help us map the radio sky by matching the radio jets and filaments to the galaxies (via the infrared images) from whence they came.

This is a matching & recognition problem that humans are still best at, especially in cases where there are radio jets or multiple sources. And it’s an important task, one that will only become more important as the next generation of radio surveys and instruments come online and start producing enormous amounts of data. So if you’re willing to help, please try out the new Radio Galaxy Zoo and help find some growing black holes — and thank you!

Bars as Drivers of Galactic Evolution

Hello everyone – my name is Becky Smethurst and I’m the latest addition to the Galaxy Zoo team as a graduate student at the University of Oxford. This is my first post (hopefully of many more) on the Galaxy Zoo blog – enjoy!

So far there have been over 100 scientific research papers published which make use of your classifications, some of which have been written by the select few Galaxy Zoo PhD students (most of us are also previous Zooites). The most recently accepted article was written by Edmund, who wrote a blog post earlier this year on how bars affect the evolution of galaxies. As part of the astrobites website, which is a reader’s digest of research papers for undergraduate students, I wrote an article summarising his latest paper. Since the Zooniverse team know how amazing the Galaxy Zoo Citizen Scientists are, we thought we’d repost it here for you lot to read and understand too. You can see the original article on astrobites here, or read on below.

Title: Galaxy Zoo: Observing Secular Evolution Through Bars

Authors: Cheung, E., Athanassoula, E., Masters, K. L., Nichol, R. C., Bosma, A., Bell, E. F., Faber, S. M., Koo, D. C., Lintott, C., Melvin, T., Schawinski, K., Skibba, A., Willett, K.

Affiliation: Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064

Galactic bars are a phenomenon that were first catalogued by Edwin Hubble in his galaxy classification scheme and are now known to exist in at least two-thirds of disc galaxies in the local Universe (see Figure 1 for an example galaxy).

Throughout the literature, bars have been associated with the existence of spiral arms, rings, pseudobulges, star formation and even Active Galactic Nuclei.

Bars are a key factor in our understanding of galactic evolution as they are capable of redistributing the angular momentum of the baryons (visible matter: stars, gas, dust etc.) and dark matter in a galaxy. This redistribution allows bars to drive stars and gas into the central regions of galaxies (they act as a funnel, down which material flows to the centre) causing an increase in star formation. All of these processes are commonly known as secular evolution.

Our understanding of the processes by which bars form and how they consequently affect their host galaxies however, is still limited. In order to tackle this problem, the authors study the behaviour of bars in visually classified disc galaxies by looking at the specific star formation rate (SSFR; the star formation rate as a fraction of the total mass of the galaxy) and the properties of their inner structure. The authors make use of the catalogued data from the Galaxy Zoo 2 project which asks Citizen Scientists to classify galaxies according to their shape and visual properties (more commonly known as morphology). They particularly make use of the parameter from the Galaxy Zoo 2 data release, which gives the fraction of volunteers who classified a given galaxy as having a bar. It can be thought of as the likelihood of the galaxy having a bar (i.e. if 7 people out of 10 classified the galaxy as having a bar, then the likelihood is

= 0.7).

They first plot this bar likelihood using coloured contoured bins, as shown in Figure 2 (Figure 3 in this paper), for the specific star formation rate (SSFR) against the mass of the galaxy, the Sérsic index (a measure of how disc or classical bulge dominated a galaxy is) and the central mass density of a galaxy (how concentrated the bulge of a galaxy is). At first glance, no trend is apparent in Figure 2, however the authors argue that when split into two samples: star forming (log SSFR > -11 ) and quiescent (aka “red and dead” galaxies with log SSFR < -11

) galaxies, two separate trends appear. For the star forming population, the bar likelihood increases for galaxies which have a higher mass and are more classically bulge dominated with a higher central mass density; whereas for the quiescent population the bar likelihood increases for lower mass galaxies, which are disc dominated with a lower central mass density.

- Figure 2: The average bar likelihood shown with coloured contoured bins for the specific SFR (SFR with respect to the the total mass of the galaxy) against (i) the mass of the galaxy, (ii) the Sérsic index (a measure of whether a galaxy is disc (log n > 0.4) or bulge (log n < 0.4) dominated and (iii) the central surface stellar mass density. This shows an anti-correlation of

with the specific star formation rate. The SSFR can be taken as a proxy for the amount of gas available for star formation so the underlying relationship that this plot suggests, is that bar likelihood will increase for decreasing gas fraction.

Bars become longer over time as they transfer angular momentum from the bar to the outer disc or bulge. In order to determine whether the trends seen in Figure 2 are due to the evolution of the bars or the likelihood of bar formation in a galaxy, the authors also considered how the properties studied above were affected by the length of the bar in a galaxy. They calculate this by defining a property , a scaled bar length as the measured length of the bar divided by a measure of disc size. This is plotted in Figure 3 (Figure 4 in this paper) against the total mass, the Sérsic index and the central mass density of the galaxies. with the population once again split into star forming (log SSFR >-11

) and quiescent (log SSFR < -11

) galaxies.

As before, Figure 3 shows that the trend in the star forming galaxies is for an increase in for massive galaxies which are more bulge dominated with a higher central mass density. However, for the quiescent population of galaxies,

decreases for increasing galactic mass, increases up to certain values for log n and

and after which the trend reverses.

The authors argue that this correlation between and

within the inner galactic structure of star forming galaxies is evidence not only for the existence of secular evolution but also for the role of ongoing secular processes in the evolution of disc galaxies. Furthermore, they argue since the highest values of

are found amongst the quiescent galaxies (with log n ~ 0.4) that bars must play a role in turning these galaxies quiescent; in other words, that a bar is quenching star formation in these galaxies (rather than an increase in star formation which has been argued previously). They suggest that this process could occur if the bar funneled most of the gas within a galaxy, which is available for star formation, into the central regions, causing a brief burst of star formation whilst starving the majority of the outer regions. This evidence becomes another piece of the puzzle that is our current understanding of the processes driving galactic evolution.

Galaxy drumstick, anyone?

Over the past six years, Galaxy Zoo volunteers have spotted innumerable patterns in the shapes of regular, merging, and fortuitously overlapping galaxies in the various surveys. While we’ve had great success with letters of the alphabet and with animals, searches of both the Forum and Talk haven’t revealed many turkeys so far. In recognition of Thanksgiving in the U.S. this week, we offer this turkey drumstick (or tofurkey, if you’re a veggie like some team members) spotted last year by volunteer egalaxy.

For those of you who get them, enjoy the break — and let us know what you think about this interesting galaxy (or possible overlapping pair)!

UPDATE: Next Live Hangout: Tuesday, 19th of November, 7 pm GMT

Our next hangout will be next Tuesday at 7 pm European time / 6 pm UK / 3 pm in Chile / 1 pm EST / 10 am PST.

Update: Our next hangout will be next Tuesday at 8 pm European time / 7 pm UK / 4 pm in Chile / 2 pm EST / 11 am PST.

I mention Chile above because two team members will be at a conference in Chile at the time (spreading the word about Galaxy Zoo is a tough job, but someone’s got to do it) and will try to be on the hangout with us.

What do you want us to talk about? We have some ideas but if you have questions, please let us know!

Just before the hangout we’ll update this post with the embedded video, so you can watch it live from here. If you’re watching live and want to jump in on Twitter, please do! we use a term you’ve never heard without explaining it, please feel free to use the Jargon Gong by tweeting us. For example: “@galaxyzoo GONG dark matter halo“.

See you soon!

Galaxy Zoo and undergraduate research: spiral arms, colors, and brightnesses

The guest post below is by Zach Pace, an undergraduate physics student at the University of Buffalo. Zach worked at the University of Minnesota during the summer of 2013 through the NSF’s Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) program. Zach is continuing to work with Galaxy Zoo data as part of his senior thesis.

Hi, everyone–

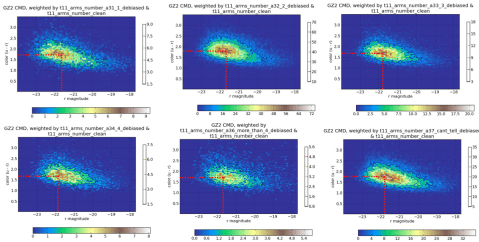

My name is Zach Pace. I’m an undergraduate physics student from the University at Buffalo, and I’ve been working on the Galaxy Zoo 2 project at the University of Minnesota since late May with Kyle Willett and Lucy Fortson. My investigation has been twofold: I have been diagramming specific morphological categories in color-magnitude space, and also fitting those data to mathematical functions.

As many readers probably know, a galaxy’s magnitude (overall brightness in the red band, on a log scale) and a galaxy’s color (the difference between the blue magnitude and a red band) are two important quantities for determining what a galaxy might look like (and how it might evolve). Brighter galaxies have more mass (more stars produce more light, of course), and bluer galaxies have a more recent star formation history (this is because young, bright stars tend to be large, bright, and blue). In terms of the whole population, we know, for instance, that elliptical galaxies tend to concentrate in a red sequence, and have typical colors between 2.25 and 2.75. Conversely, the vast majority of spiral galaxies concentrate in a blue cloud between colors 1.25 and 2.0. These two populations are clearly separated in color-magnitude space (this can be seen in the accompanying 2-D histogram, made from Zoo 2 data).

Color-magnitude diagram (CMD) for objects in Galaxy Zoo 2. The lines show fits to the two main populations of elliptical (red) and spiral (blue) galaxies, following the method of Baldry et al. (2004). The green line shows an approximate separation between them.

One of the main goals of Zoo 2 is to gauge the extent to which morphology informs physical characteristics like color and magnitude, so my objective for the summer was to come up with good representations of color and magnitude for all of the smaller sub-populations in Zoo 2.

Several of my results were interesting and surprising. For instance, it has been suggested that spiral galaxies with more arms and spiral galaxies with tighter arm winding (which is to say, a shallower pitch angle) tend to be brighter and bluer. This can be intuitively understood as follows: tighter winding of spiral arms and the presence of more spiral arms indicate, on average, denser gas clouds in those arms, which is tied to increased star formation and bluer color. However, I wasn’t able to measure this in the Zoo 2 data (all the differences were on the order of the histograms’ bin size, about 0.1 magnitude, or about a 10% difference in brightness). This suggests that spiral galaxies, no matter arm multiplicity or winding, are drawn from the same base population.

Color-magnitude diagram (CMD) for spirals in GZ2, split by the number of spiral arms identified in each galaxy. The distribution of colors and magnitudes for galaxies are statistically similar, no matter what the number of spiral arms.

I also came across something unexpected when looking at bulge sizes in face-on disk galaxies. The distribution of galaxies classified by users as bulgeless is starkly different from the distribution of obvious bulge and bulge-dominated galaxies. Furthermore, the population with a bulge that is just noticeable seems to form an intermediate population between the bulgeless and bulge. This observation is also borne out in edge-on disk galaxies: the population of bulgeless edge-on galaxies has a similar shape to the population of face-on galaxies, albeit with stronger reddening on the bright end.

Color-magnitude diagram (CMD) for disk galaxies in Galaxy Zoo 2, split by the relative size of the central bulge. Galaxies that appear to have no central bulge (top) have very different colors and luminosity than those with dominant bulges (bottom).

To fit the distributions, I used a method pioneered about 10 years ago by Ivan Baldry, which fits one parameter after another in our profile functions to find a distribution that converges onto the best fit. It works okay (but not great) for the whole sample, and it fails pretty badly when working with the smaller sub-populations. This is because I have to fit many parameters at once, and do that a bunch of times in a row for the fit to converge, so there are a lot of points of failure. I’m working now at Buffalo towards finding a different and better fitting routine, which will allow us to represent more distributions mathematically.

If you have any questions, feel free to comment below.

Galaxy Zoo: Now Available In Chinese (Mandarin)

What follows is a press release from Academia Sinica’s Institute of Astronomy & Astrophysics, regarding the new Mandarin Galaxy Zoo. Below is some context for English speakers and regular Galaxy Zoo users.

What follows is a press release from Academia Sinica’s Institute of Astronomy & Astrophysics, regarding the new Mandarin Galaxy Zoo. Below is some context for English speakers and regular Galaxy Zoo users.

在可觀測宇宙散佈千億星系,許多以美麗著稱。光芒閃耀的每個星系裡,都有數十億顆恆星。新推出的「星系動物園」網站中文版,和研究星系大有關聯,不管有沒有天文背景,只要有網路,無論愛上網咖還是宅宅A咖,只花二分鐘也可參與星系分類的Galaxy Zoo計畫,自2007年以來,在英、美、歐地區成為網民科普熱門運動,已經招募87萬名星系分類員(志工),大受歡迎。原來星星可以這樣數。

2013年10月份,在中研院年度開放日這天,由中研院天文所推廣成員共同翻譯完成的中文版網站,也選在這天首度公開試用,在場民眾只花二分鐘做星系形態辨識,分類結果就成為整個科學計畫資料庫的一部分,換言之,中文版的星系分類員是實際參與貢獻了科學研究,這吸引不少熱心學生和家長,「做天文只要二分鐘,很酷!而且學到新知識。」

從”Galaxy Zoo”到「星系動物園」,天文所推廣組表示,「兩年前就想過要做」的這個計畫,今年8月,一經天文所博士後研究Meg Schwamb再次提議,立刻獲得響應,網站中文化水到渠成,也讓台灣在全球天文學界再博得一次「亞洲第一」的小獎勵(註:目前該網站只有英文版和西語版)。推廣組表示,由於星系資料持續新增,分類員在圖像庫中撈到某個從未曾被人見過的星系,或「全球第一人」這樣的說法,確實所言不虛。

來自英國的Galaxy Zoo計畫主持人Chris Lintott表示,在網民科學網站傘狀計畫下的項目還有很多,天文類的譬如行星獵人(Planet Hunters)和火星氣候(Planet Four)。這些都必須靠各位地球人以好眼力來熱情相挺,電腦可幫不上忙。為什麼呢?歡迎上網一探究竟:http://www.galaxyzoo.org/?lang=zh

眨眼睛、動滑鼠、幫幫星系分分類!

Last weekend, led by Dr. Meg Schwamb (who is part of the Planet Hunters and Planet Four teams), a team of Taiwanese astronomers helped introduced a Chinese (Mandarin) version a Galaxy Zoo to the public on the Open House Day of Academia Sinica, the highest academic institution in Taiwan.

A big crowd of enthusiastic students and parents, attracted by the long queue itself, visited the ‘Citizen Science: Galaxy Zoo’ booth to try the project hands-on by doing galaxy classifications. They were excited to participate in scientific research and enjoyed it very much.

“Amazing! In just two minutes, we have helped astronomer doing their research, it’s so cool! Also, we learn new astronomical facts we never knew before. It’s a good show.”

The Education Public Outreach team of Academia Sinica’s Institute of Astronomy & Astrophysics (a.k.a. “ASIAA”), has helped translated Galaxy Zoo from English to Chinese (Mandarin). The main translator, Lauren Huang said, “we were keen to do a localized version for Galaxy Zoo since 2010, so when Meg brought up this nice idea again, we acted upon it at once.” In less than six weeks, it was done. The other translator, Chun-Hui, Yang, who contributed to the translation, said that she likes the website’s sleek design very much. “I think the honor is ours, to take part in such a well-designed global team work!” Lauren said.

Talking about the translation process process, Lauren provided an anecdote that she thought about giving “zoo” a very local name, such as “Daguanyuan” (“Grand View Garden”), a term with authentic Chinese cultural flavour, and is from classic Chinese novel Dream of the Red Chamber. She said, “because, my personal experience in browsing the Galaxy Zoo website has been very much just like the character Ganny Liu in the classics novel. Imagine, if one flew into the virtual image database of the universe, which contains all sorts of hidden treasures waiting to be explored, what a privilege, and how little we can offer, to help on such a grandeur design?” However, the zoo is still translated as “Dungwuyuan”, literally, just as “zoo “. Because that’s what some Chinese bloggers have already accustomed to, creating a different term might just be too confusing.

You can check out the Traditional Character Chinese (Mandarin) version of Galaxy Zoo at http://www.galaxyzoo.org/?lang=zh

Studying the slow processes of galaxy evolution through bars

Note: this is a post by Galaxy Zoo science team member Edmond Cheung. He is a graduate student in astronomy at UC Santa Cruz, and his first Galaxy Zoo paper was accepted to the Astrophysical Journal last week. Below, Edmond discusses in more depth the new discoveries we’ve made using the Galaxy Zoo 2 data.

Observations show that bars – linear structures of stars in the centers of disk galaxies – have been present in galaxies since z ~ 1, about 8 billion years ago. In addition, more and more galaxies are becoming barred over time. In the present-day Universe, roughly two-thirds of all disk galaxies appear to have bars. Observations have also shown that there is a connection between the presence of a bar and the properties of its galaxy, including morphology, star formation, chemical abundance gradients, and nuclear activity. Both observations and simulations argue that bars are important influences on galaxy evolution. In particular, this is what we call secular evolution: changes in galaxies taking place over very long periods of time. This is opposed to processes like galaxy mergers, which effect changes in the galaxy extremely quickly.

Examples of galaxies with strong bars (linear features going through the center) as identified in Galaxy Zoo 2.

To date, there hasn’t been much evidence of secular evolution driven by bars. In part, this is due to a lack of data – samples of disk galaxies have been relatively small and are confined to the local Universe at z ~ 0. This is mainly due to the difficulty of identifying bars in an automated manner. With Galaxy Zoo, however, the identification of bars is done with ~ 84,000 pairs of human eyes. Citizen scientists have created the largest-ever sample of galaxies with bar identifications in the history of astronomy. The Galaxy Zoo 2 project represents a revolution to the bar community in that it allows, for the first time, statistical studies of barred galaxies over multiple disciplines of galaxy evolution research, and over long periods of cosmic time.

In this paper, we took the first steps toward establishing that bars are important drivers of galaxy evolution. We studied the relationship of bar properties to the inner galactic structure in the nearby Universe. We used the bar identifications and bar length measurements from Galaxy Zoo 2, with images from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS). The central finding was a strong correlation between these bar properties and the masses of the stars in the innermost regions of these galaxies (see plot).

This plot shows the central surface stellar mass density plotted against the specific star formation rate for disks identified in Galaxy Zoo 2. The colors show the average value of the bar fraction for all galaxies in that bin. This plot shows that the presence of a bar is clearly correlated with the global properties of its galaxy (Σ and SSFR).

We compared these results to state-of-the-art simulations and found that these trends are consistent with bar-driven secular evolution. According to the simulations, bars grow with time, becoming stronger (they exert more torque) and longer. During this growth, bars drive an increasing amount of material in towards the centers of galaxies, resulting in the creation and growth of dense central components, known as “disky pseudobulges”. Thus our findings match the predictions of bar-driven secular evolution. We argue that our work represents the best evidence of bar-driven secular evolution yet, implying that bars are not stagnant structures within disk galaxies, but are instead a critical evolutionary driver of their host galaxies.