Clicking 10 Billion Years Into The Past

Astronomers use funny units. We have the light-year, which sounds like a time but is actually a distance. There’s the parsec, a historical (but still used) unit of distance that was famously mis-used as a time in Star Wars. And then there’s redshift, which is actually a velocity — distance divided by time — but which, because of the expansion of the universe, astronomers get to use as a proxy for distance.

While it may be convenient for us to use distance units where we set a mind-blowingly large number equal to 1, it doesn’t really help us communicate our work to the public. If I note that the galaxy images from CANDELS look a little different from the galaxies in the SDSS because the CANDELS galaxies are typically at a redshift of 2, that’s pretty meaningless. But it’s a little different to think of the fact that, when you classify a galaxy from CANDELS, you may be looking three-quarters of the way to the edge of the visible universe, and seeing the galaxy as it was 10 billion years ago.

During this hangout, we announced that your clicks and classifications of the CANDELS galaxies have been moving at such an impressive rate that the first round is finished. Every galaxy has enough classifications for us to get a very good sense of what its morphology is. It may be that, for some of the galaxies where there are clearly more details to flush out, we will ask for a few more classifications per galaxy. And there will probably be future CANDELS images from survey fields that are still being completed. So, don’t worry, there will still be plenty of opportunities to classify galaxies as they were 10 billion years ago!

In the meantime, though, we’re getting ready not just to do the scientific analysis, but to share Galaxy Zoo results with our colleagues around the world. The summer conference season is upon us, and many of us have given and are giving talks and posters at various meetings in various cities. This includes not just the recent meeting highlighting the importance of galaxy morphology in the era of large surveys at the Royal Astronomical Society and the upcoming ZooCon in Oxford and Galaxy Zoo meeting in Sydney, but also several more general conferences, including the 222nd American Astronomical Society meeting and the upcoming UK National Astronomy Meeting. Spreading the word about the scientific results we’re finding with Galaxy Zoo is one of the most important parts of our job — and it doesn’t hurt that in order to do that we have to visit some very interesting places. During the hangout we chatted a bit about that and also took some of your questions:

Note: although it was a beautiful sunny day in Oxford, the variable audio quality is not because I was occasionally distracted looking out the window. I don’t think it was the new microphone, either. We’ll look into it, but in the meantime I’ve tried to equalize the podcast version with some after-editing, so hopefully that is slightly better.

A Galaxy Zoo science team dinner

Almost a month ago now, Galaxy Zoo hosted a Specialist Discussion at the Royal Astronomical Society in London, on the topic of Morphology in the Era of Large Surveys. It was actually a wonderful day full of interesting talks and discussion, and we will be sharing more of the science content from the discussion as soon as we find time to put that together.

One of the other fun things about this meeting was that as well as the fantastic invited speakers, mostly from outside Galaxy Zoo collaboration, many members of the Galaxy Zoo science team were able to attend and contribute talks. We had representatives of team members from Minnesota, Oxford, Nottingham, Portsmouth, Hertfordshire and Zurich in attendance. It was a great chance for us to catch up both scientifically and socially. Below is a set of round table pictures we took during our “team dinner” that Friday night in London’s Chinatown. The captions always list names from left to right. The poor photography is entirely my fault!

Kevin Schawinski (Zurich, Galaxy Zoo Co-founder); Chris Lintott (Oxford; Galaxy Zoo Co-founder and “PI of the Universe” – or maybe just the Zooniverse is enough); Jen Gupta (Portsmouth – Zooteach/Education)

Sugata Kaviraj (Oxford -> Hertfordshire, Dust lanes in early types and more); Tom Melvin (Portsmouth PhD student on redshift evolution of bars); Steven Bamford (Nottingham, GZ1 Data Guru, Colour-morphology and environment and more)

Kyle Willet (Minnesota; GZ2 Data Guru), Brooke Simmons (Oxford, Black Holes in Bulgeless Galaxies, Google+ Hangouts and much more), Boris Haussleur (Nottingham->Oxford; CANDELS team member)

Next GZ Hangout: Thursday, June 6th, 15:00 GMT

It’s been a while since we’ve had a hangout — how about this Thursday?

8:00 PDT, 11:00 EDT, 15:00 GMT, 16:00 BST, 17:00 CET, 18:00 CAT. Have questions? Post them here or tweet at us (@galaxyzoo). Just before the hangout starts, we’ll embed the video here so you can watch from the blog.

The best way to send us a comment during the live hangout is to tweet at us, but you can also leave a comment on this blog post, or on Google Plus, Facebook or YouTube, which we’ll also try to keep an eye on. See you soon!

Updates to Talk

The good news: the developers are currently hard at work migrating Talk to the latest version, which has many improvements over the old version. When the update is finished, the Talk home page will contain lots more information about each new post (including thumbnails!), the discussions should be easier to navigate, and the collections will be easier to navigate and manage — just for a start. We’ve been looking forward to this upgrade for a while, and once it’s completed it will make discussions of your discoveries even better.

The bad news: Talk will be down for a few hours while the upgrade actually takes place. And, as with any significant update that includes changing the way your favorite website appears on a page, it may take some getting used to. But hang in there and you’ll find your way around. Also, please feel free to ask questions, either here or on Talk itself. (Also also, thanks for bearing with us.)

The other good news: The main classification site isn’t affected at all — so you can still classify galaxies to your heart’s content, without interruption!

Observing Run: Raw Data versus Finished Product

So let’s say you have a galaxy:

And you know this galaxy has a growing black hole, and probably hasn’t had any significant mergers, because it has very little, if any, bulge. Which means you have two questions: 1) what counts as significant? and 2) how little is very little?

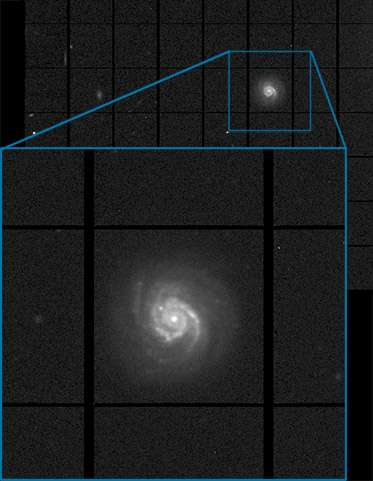

To answer the first question, you’d like to look for the faint stellar streams that signify the remnants of a minor merger. The optical images you already have aren’t even close to deep enough to see something like this:

NGC 5907: the Splinter galaxy. Credit: R. Jay Gabany

But if you could see that for your galaxy, you could start to put together its minor merger history and answer that first question.

Of course, that kind of depth is not easy. The group that took that data most likely spent weeks observing that one source, and there are many technical challenges involved. You may be in luck, though: you have a bigger telescope, which means you probably only need one night to get a single-filter optical image at the same depth.

So you go to the telescope, and you take some data. After 5 minutes, this is what you have:

Which … doesn’t look so great, actually, until you clean it up a bit by correcting for the different effects that come with a huge mosaic of CCD chips, like different noise levels and so forth. Luckily, the people who wrote the code to observe with this instrument have provided a “first-look” button that automatically does that pretty well:

That’s better. You can see that even with 5 minutes of observing time, you’re close to the depth you already had. To get what you need, though, you don’t need 5 minutes of exposure. You need 5 hours.

But you don’t want to just set the telescope to observe for 5 hours and hit “go”. In fact, you can’t do that. If you do, those well-behaved little stars near your galaxy will be so bright on the detector that they’ll “saturate”, filling their pixels with electrons that then spill out into nearby pixels. This detector in particular doesn’t handle that very well, so you need to avoid that. And what if something happens in those 5 hours? What if a cosmic ray — or many — hits your detector? What if a satellite passes over? What if the telescope unwraps? While that looks kind of cool:

When the telescope rotates to +180 degrees, it stops tracking and goes -360 so that it can keep tracking from -180. Otherwise cables plugged in to walls + twirling round and round = unhappy telescope.

It wrecks the whole exposure. Plus, those chip gaps are right where your stellar streams might be. You’d like to get rid of them.

So you solve all of these problems at once by observing multiple exposures and moving the telescope just a little in between exposures.

You end up getting your 5 hours’ exposure time by doing lots of dithers — about 50 of them, to be exact, mostly between 5 and 10 minutes apiece. This has several advantages and a few disadvantages. You can throw out any weird exposures (like the unwrap above) without losing very much time, but then you have to combine 50 images together. And that, frankly, is kind of a pain.

And this is a new instrument, and the reduction pipeline (the routines you follow to make the beautiful finished product) doesn’t fully exist yet, and what does exist is complex — and, for the moment, completely unknown to you.

So the beautiful finished product will have to wait.

In the meantime, you have a few more galaxies to look at, and that second question to try and answer, on future nights and in a future blog post.

Why I’m at WIYN: Mergers and Bulgeless Galaxies

At the start of this year, our paper on bulgeless galaxies with growing black holes was published. These galaxies are interesting because each is hosting a feeding supermassive black hole at its center, a process typically associated (at least by some) with processes like mergers and interactions that disrupt galaxies — yet these galaxies seem to have evolved for the whole age of the universe without ever undergoing a significant merger with another galaxy. In fact, they must have had a very calm history even among galaxies that haven’t had many mergers. If these galaxies were people, they’d be people who had grown up as only children in a rural town where they always had enough food for the next meal, but never for a feast, who never jaywalked or stayed out in the sun too long, and whose parents never yelled at them — because it was never necessary. Sounds boring, perhaps, until you see the screaming goth tattoo.

Major mergers? Not for these galaxies. (Credit: V. Springel. Except the big, vicious X. That’s all me.)

We see the evidence of the tattoos — rather, the growing black holes — by examining the galaxies’ optical spectra. But how do we know they’ve had such calm histories? You told us. Galaxy Zoo classifications revealed that, once you account for the presence of the bright galactic nucleus, these galaxy images have no indication of a bulge. And bulges are widely considered to be an inevitable byproduct of significant galaxy mergers, so: no bulge, no merger.

Of course, that’s a very general statement and it begs many follow-up questions. For instance: what counts as a “significant” merger? These galaxies had to have grown from the tiny initial fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background to the collections of hundreds of billions of stars we see today, and we know that process was dominated by the smooth aggregation of matter, but just how smooth was it? If two galaxies of the same size crash together, obviously that’s a merger, and that will disrupt both galaxies enough to create a prominent bulge (or even result in an elliptical galaxy). If one galaxy is half the size of the other, that’s still considered a “major” merger and it almost certainly still creates a bulge. But what if one galaxy is one-quarter the size of the other? One tenth? One hundredth? At what level of merger do bulges start to be created? Simulations tend to either not address this question, or come up with conflicting answers. We just don’t know for sure how much mass a disk galaxy can absorb all at once before its stars are disrupted enough to make a detectable bulge.

However, we may be able to constrain this observationally. Galaxy Zoo volunteers are great at finding the tidal features that indicate an ongoing or recent merger, and the more significant the merger, the brighter the features. Mostly the SDSS is only deep enough to detect the signs of major mergers, which are easier to see, but which settle or dissipate relatively quickly. In a more minor merger, on the other hand, the small galaxy tends to take its sweet time fully merging with the larger galaxy, and with each orbital pass it becomes more stretched out, meaning faint tidal features persist. The Milky Way has faint stellar streams that trace back to multiple minor mergers. But if we want to see their analogs in galaxies millions of light-years away, we’re going to need to look much deeper than the SDSS does.

A very deep image of M63 by Martinez-Delgado et al. (2010), demonstrating that these observations are technically challenging, but possible.

So we were thrilled when we got time on the 3.5-meter WIYN telescope. Of the six nights we got, 2 are set aside for infrared exposures to make sure these galaxies aren’t just hiding bulges behind dust, and the other 4 are for ultra-deep imaging to see what (if any) faint tidal features exist around some of these bulgeless galaxies. If we find tidal streams, we can use their morphologies and brightness to help us figure out the size of merger they indicate (by comparing to simulations). If we don’t find any, then these galaxies really have had no significant mergers, and the growth of supermassive black holes via purely calm evolutionary processes is confirmed. (Long live the vanilla farm kid with the wicked tattoo!)

So how’s it going so far? Reasonably well: conditions haven’t been perfect, but until tonight we hadn’t lost much time to full clouds or dome closures. Tonight, though there’s not a cloud in the sky, there’s so much dust in the air that the domes are closed to prevent damage to the optics. Obviously I’m sad about that — it means we’ll miss one of our targets — but in between various incantations to the gods to clear the air so we can re-open, I’m working on an initial reduction and stacking of all the images I’ve taken over the past couple of days, so that I can (hopefully) give everyone a sneak peek at the results soon!

Observing Run: WIYN, Kitt Peak – First Report

I’ve been both excited and nervous about my trip to Kitt Peak. I’m excited because observing is fun and the science is cool, but the program I have planned is also technically challenging and uses a brand new instrument, which is a little scary.

In addition, although I’m plenty experienced with data, I haven’t done a lot of hands-on observing. My PhD thesis used Hubble data, and Galaxy Zoo uses both Hubble and SDSS data — neither of which you take yourself. Because observing is a useful skill for my profession, I made sure to get some experience while I was in grad school, but this is my first solo run to collect data for my own project. I’m here to get very deep images of some of our bulgeless AGN host galaxies, so if it doesn’t work out I’m probably going to be heartbroken. And clouds or technical issues are one thing, but I’ll be even more upset if I fail because I make a mistake that a seasoned observer wouldn’t have. I don’t want to let the Galaxy Zoo participants down! So I’ve been reading the instrument manuals and scouring papers that have done similar work in the past. The pressure is on.

I arrived the night before my first night so that I could “eavesdrop” and start to learn the new instrument on the 3.5-meter WIYN telescope, called pODI. Eventually it will just be the One Degree Imager, but for now it’s only partially complete — which is fine for me, as I only need a fraction of the total area ODI will eventually cover. But Kathy Rhode, who studies globular clusters in nearby galaxies, has slightly larger targets:

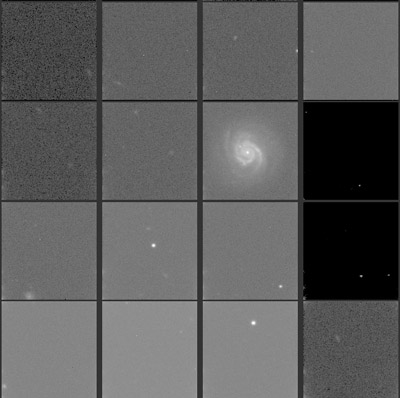

This is just one of many images Kathy took, all of which will eventually be combined to fill in the chip gaps and get rid of the usual artifacts. The instrument is working very well — it’s a good thing instruments don’t get as tired as their observers!

Another good reason to arrive a night early is to give yourself time to get adjusted to the observing schedule.

For my own first night, I was assisted by a startup person, an ODI system scientist who knows the instrument backwards and forwards. He walked me through everything, and stuck around to make sure my science observations were starting off right. He was joined by two others, both software gurus who are either writing code for ODI or for similar instruments. Along with Doug, the veteran telescope operator, there was a lot of expertise in the room. They were very patient as I asked all my questions (and made some suggestions — the software is still in progress), and my first science exposure of the night looked exactly as I had hoped:

Okay, like I said, pODI is a little bit more area than I need at the moment. Here’s a zoom in to the central detector grid:

So. Why am I observing these objects? What am I hoping to learn? More soon… for now it’s the start of my second night, and I have to get started on calibrations!

Using Space Warps to Discover and Weigh Galaxies

John Wheeler once summarized General Relativity as “Matter tells space how to curve, and space tells matter how to move.” While that is a handy description, and while there have been many textbooks written, lectures given and websites constructed to explain this, the quote itself doesn’t address what happens to the light streaming through the universe as it encounters the warped space curved by matter.

The simple answer is: it curves too, and Einstein’s equations provide predictions for exactly how it works. In fact, observations of the bending of starlight around the Sun were one of the first implemented tests of General Relativity, and it passed with flying colors. On the scale of the Universe, the Sun isn’t that massive, but it’s massive enough to bend the light just a little, and by exactly the amount the equations predicted.

The simple answer is: it curves too, and Einstein’s equations provide predictions for exactly how it works. In fact, observations of the bending of starlight around the Sun were one of the first implemented tests of General Relativity, and it passed with flying colors. On the scale of the Universe, the Sun isn’t that massive, but it’s massive enough to bend the light just a little, and by exactly the amount the equations predicted.

Those equations say that more matter in the same place is more likely to produce a strong lens effect, distorting and magnifying a background source. So what happens when you have a *lot* of matter, say, in a big galaxy or a cluster of galaxies?

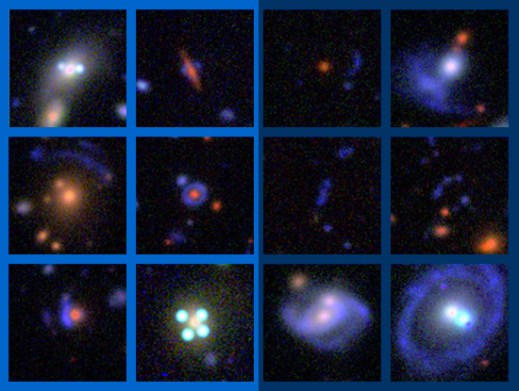

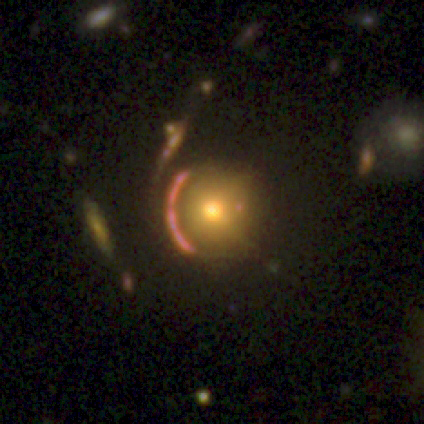

From left to right: a) an Einstein cross (credit: NASA/ESA); b) an example from the Space Warps dataset; c) a known lens in CANDELS that Galaxy Zoo users spotted.

Some pretty impressive configurations, which are rare but which humans are best at finding — hence Space Warps, the Zooniverse’s newest project and our astronomical project sibling. Co-lens-experts Phil Marshall and Aprajita Verma joined us during this hangout to describe how they use gravitational lenses to weigh galaxies. In particular, they can tell the difference between Dark Matter and “matter that’s dark” — the former being the exotic particles that are very different from stars and gas and planets and people, and the latter being normal matter that isn’t bright, such as brown dwarf “stars” that never actually ignited.

Note: Google+ was feeling a bit out of sorts, so the first minute or so of the broadcast was cut off, during which time Bill Keel showed us the first known image of a gravitational lens, from 1903. We went on to talk about all of the above, and more besides, including the importance of simulated lenses, why the images Space Warps uses are specially tuned to help us find lenses, and how the science team (which includes citizen scientists from Galaxy Zoo!) plan to turn our clicks into discoveries.

(or download the podcast mp3 here)

Notice my swapping of pronouns to “we” — I’m not on the Space Warps science team, but I’ve done nearly 100 classifications now myself! I can’t wait to see the results start to come in from this project.

Engage!

Meet our new sibling project: Space Warps, where you can help find rare and spectacular gravitational lenses. Many citizen scientists took part in building this project, and it’s already proven very popular just in its first day! But the science team still needs your help.

Project leads Phil Marshall and Aprajita Verma will be joining us tomorrow on our live Hangout to talk in more detail about gravitational lenses and what they want to achieve with the Space Warps project. Please join us, and have a look at spacewarps.org in the meantime!

Hooray! Space Warps is live, and the spotters are turning up in numbers. Check out the site at spacewarps.org – there’s a few little bugs that Anu, Surhud and the dev team are ironing out, but basically it’s looking pretty good! Thanks very much to everyone who’s helped out in the last few months – your feedback has been very useful indeed in designing a really nice, easy to use website that hopefully will enable many new discoveries. And to all of you who are new to Space Warps – welcome!

If you’re feeling really keen, why don’t you come and hang out in the discussion forum at talk.spacewarps.org? We’re starting to tag images to help organise them, and the more interesting conversations we have there, the more useful it will be for the newer volunteers. And of course, you can vote on the candidates spotted by other people…

View original post 41 more words

Next GZ Hangout: Thursday, May 9th, 15:00 GMT – with special guests!

Our next hangout will be this Thursday, the 9th of May, at 15:00 GMT, which is 8:00 PDT, 11:00 EDT, 16:00 BST, 17:00 CET, 18:00 CAT… and midnight in Japan.

Why Japan? Does that have anything to do with the special guest participant(s)? And why is there an image of a gravitational lens on this blog post?

You’ll have to tune in to see!

The best way to send us a comment during the live hangout is to tweet at us (@galaxyzoo), but you can also leave a comment on this blog post, or on Google Plus, Facebook or YouTube, which we’ll also try to keep an eye on. See you soon!