Galaxy Zoo gets highlighted by the 2010 Decadal Survey

Every decade, the US astronomy community gets its leaders together to write up a report on the state of the field and to recommend and rank major projects that should be supported by the government over the next decade. It’s a blue print, a wish list and often also a sober exercise in what to fund (a little) and what to cut (a lot). The current Decadal Survey was finally released by the US National Academies last Friday and every astronomer is poring over it to see if their project or telescope is ranked highly.

Galaxy Zoo isn’t competing for hundreds of millions of dollars in funding to launch a space observatory, but it did get not just one but two mentions in the 2010 Decadal Survey, one in the text and a figure. For those of you who are keen to read the whole thing for themselves, you can get the report at the National Academies website here (you have to click on download and give them your details to get the free PDF download). Here on the blog we only show you the highlights, i.e. the Galaxy Zoo mentions. From the text in the section on “Benefits of Astronomy to the Nation” where they discuss how “Astronomy Engages the Public in Science”:

Astronomy on television has come a long way since the 1980 PBS premier of Carl Sagan’s ground-breaking multipart documentary Cosmos. Many cable channels offer copious programming on a large variety of astronomical topics, and the big three networks occasionally offer specials on the universe too. Another barometer of the public’s cosmic curiosity comes from the popularity of IMAX-format films on space science, and the number of big-budget Hollywood movies that derive their plotlines directly or indirectly from space themes (including five of the top ten grossing movies of all time in America). The internet plays a pervasive role for public astronomy, attracting world-wide audiences on websites such as Galaxy Zoo (www.galaxyzoo.org, last accessed July 6, 2010) and on others that feature astronomical events, such as NASA missions. Astronomy applications are available for most mobile devices. Social networking technology even plays a role, e.g., tweets from the Spitzer NASA IPAC (http://twitter.com/cool_cosmos, last accessed July 6, 2010).

They also have a lovely figure, which has a small blooper in it (see if you can spot it!). Word is that this is going to be corrected in the final version:

Thank you all for making Galaxy Zoo such a success!

Edwin Hubble, the man behind HST

Who is Edwin Hubble, the guy who gave the Hubble Space Telescope its name? Who is the mysterious guy behind the telescope?

Edwin Hubble

Well, actually, Edwin Powell Hubble is not the ‘man behind the telescope’ at all. He was born on 20th of November 1889 in the US and studied Physics and Astronomy in Chicago. He then, interestingly, went to Oxford, UK (now, of course, one of the main departments participating in Galaxy Zoo), to study Jurisprudence, later Spanish. Given that he was also very sporty (he won several state track competitions and set the state’s high school high jump record in Illinois), I think it is fair to call Hubble a person with multiple talents. In England, he also picked up some English habits and his dress code, some to the annoyance of his american colleagues in later years. I don’t know many pictures of him, the one on the right is possibly the most famous (usually used in scientific talks at least). Smoking his pipe on his desk, he really looks like an English gentlemen of his time (Well, maybe he’s lacking a hat).

Edwin Hubble died on September 28th 1953 in California (his house is now a National Historic Landmark at this location), long before the real planning for the HST had begun. Earlier ideas did exist, since 1923, after it was explained how a telescope could be propelled into Earth orbit and in 1946, Lyman Spitzer (who interestingly enough has his own space telescope named after himself now) had already discussed the advantages (which I will discuss in the next post about the planning of the HST) of an extraterrestrial observatory, but it took until 1962 for the US NAS (not NASA!) to recommend the development of a space telescope for other purposes than observing the sun (two orbiting solar telescopes were in fact already active at that time). In 1965, 12 years after Hubbles death, Spitzer was appointed head of the committee to define the scientific objectives for this new telescope, so really, he is the ‘man behind the Hubble Space Telescope’.

So why is the telescope named after Edwin Hubble then?

After some years of teaching at the university back in the US and after serving in WWI as a major, he returned to the Yerkes Observatory at the University of Chicago, where he finished his Ph.D. in 1917. The topic of his thesis was ‘Photographic Investigations of Faint Nebulae‘ (it only consists of 17 pages, a fact that possibly makes every PhD student cry nowadays). At that time, these nebulae were still considered to be part of the Milky Way, something that was waiting for a real genius and careful observer to be revealed as a mistake.

The Hooker Telescope

In 1919, Hubble took on a staff position in California at the Mount Wilson Observatory near Pasadena where he stayed until his death in 1953. Just 2 years previously, a new telescope had been finished at the site, the Hooker telescope (the slightly unfortunate name comes from John D. Hooker who funded the project), a 100-inch Reflector telescope, which today is still there and, after some recent upgrades and modifications (although preserving the historical origin wherever possible), is again used for scientific purposes. With its ‘adaptive optics’ system (see next post) its resolution today is 0.05 arcsec, the same as resolution of the HST. From 1917 to 1948, the Hooker telescope was the world’s largest telescope.

Hubble used this new, state-of-the-art telescope to continue the work on nebulae that he had started in Chicago by identifying Cepheid variable stars in them. Cepheids have the very convenient characteristic, that the period of their variability is a simple function of their brightness. So by measuring their period, astronomers can immediately tell how bright these objects are in a standard system. Measuring their apparent brightness allows to measure their actual distance. By doing this, Hubble noticed that they are far too distant to be part of our own galaxy, but instead are extragalactic systems, islands of stars (and possibly life) in the vast nothingness of space. Other distant ‘Milkyways’, just like our own.

We now call them ‘galaxies’.

Being some of the closest galaxies to our own, most of the objects that he worked on are now very famous, some also through images by the HST. The most famous of all is possibly M31, the closest big galaxy to our own, the Andromeda galaxy, or what Hubble called it, the Andromeda Nebula.

The original version of the Hubble diagram

Additionally to his distance measures of 46 galaxies Hubble further took measurements from Vesto Slipher of their escape velocity. This is basically the speed with which ‘the galaxies move away from Earth’ (what we now understand to be the cosmological redshift) and can be relatively easily measured by looking at the galaxies’ spectra, in which all spectral lines, previously known from lab experiments, are shifted by the same amount. When Hubble plotted the escape velocity of galaxies over their distance (we call this a Hubble diagram), he noticed something interesting:

The further galaxies are away from our position, the faster they move away.

This was a pretty radical idea as it proved that the Universe is not a static place at all as was widely believed before. For example, Einstein had introduced an additional term into his cosmological formula in general relativity to make his universe static/non-dynamical (something Einstein called the biggest blunder of his life after he had seen Hubble’s data. Funnily enough, this constant is now back in there to explain the accelerated expansion of the universe. It resembles the ‘dark energy’). Instead, this effect means that either the Earth is in a very special spot of the Universe where everything is flying away from it (a thought that many people, amongst them Einstein, considered wrong. The hypothesis that there is nothing special about the place where the Earth is other than that it is where we happen to live, is one of the basic fundamentals of cosmology) or there was a time in the past when everything was at the same point, much like in an explosion. Of course, we now know it was not an explosion in the traditional sense, but the beginning of time, the Big Bang.

Of course, as with most big new discoveries, these new findings were heavily discussed, not many people believed in them in the beginning. One after another, people started believing in Hubbles results, though, and the view that astronomers have on the universe changed completely. The Big Bang Theory (besides being a brilliant TV series) is now the generally accepted picture today.

As a small anecdote on the side: Due to errors in his distance measurements, Hubble measured the expansion parameter (the Hubble constant) to be 500 km/s/Mpc, which for today’s measurements is a pretty bad value, actually. After new, better data and improved data analysis were used, there were 2 big groups of people debating the real value, some said it was 50 km/s/Mpc, some others said it was 100 km/s/Mpc. For the past 10-15 years, this battle seems solved Solomonically, the value is now assumed to be just inbetween these values, somewhere between 70 and 75 km/s/Mpc. So, although Hubble was very wrong in the number that came out of his measurements, he somehow got the principle spot on.

Using the images that he had taken for his work, Hubble also came up with a system to classify these nebulae and galaxies depending on their appearance. This is what we call the Hubble sequence or the tuning fork of galaxies, and Galaxy Zoo initially used a system that was based on this diagram for their classifications.

As the Hubble Space Telescope was primarily constructed and built to observe distant galaxies (besides of course looking at objects in the solar system and interesting regions in our own galaxy), it was named after Edwin Hubble in honour of his groundbreaking work in this field.

Edwin Hubble has not only got a Space Telescope with his name, but several laws, constants and numbers are named after him, too.

Some examples:

- The Hubble constant as explained above, called H0

- The Hubble time is 1/H0 and gives the approximate age of the universe. It is currently estimated to be around 13.8 billion years.

- The Hubble length is c/H0and is equivalent to 13.8 billion lightyears. This is not the ‘size’ of the universe, but is an important length in cosmology

- The Hubble diagram as described above

- The Hubble sequence of galaxies.

- Hubble’s law

Additionally, there are:

- An asteroid: 2069 Hubble

- The crater Hubble on the Moon.

- Edwin P. Hubble Planetarium, located in a High School in Brooklyn, NY.

- Edwin Hubble Highway, the stretch of Interstate 44 passing through his birthplace of Marshfield, Missouri

- The Edwin P. Hubble Medal of Initiative is awarded annually by the city of Marshfield, Missouri – Hubble’s birthplace

- Hubble Middle School in Wheaton, Illinois—renamed for Edwin Hubble in 1992.

- 2008 “American Scientists” US stamp series, $0.41

(I think when they make you a stamp and you’ve got your own highway, you’ve really made it!)

I think that’s more or less all that I can come up with about Eddi, the post is actually quite a bit longer than I thought it would be, I’ll try to keep it shorter in the future, scout’s honour. For now, I will end with a quote from Edwin Hubble:

“Equipped with his five senses, man explores the universe around him and calls the adventure science”

With this, keep together your senses, especially seeing (the galaxies in Galaxy Zoo) and feeling (your mouse button with your index finger) and help us to do more adventurous science with the classified galaxies that you help us with (hearing, smelling and tasting are only of second order importance in astronomy, unless of course you listen to some music and have a snack while classifying 😉 ).

Thanks and Cheers,

Boris

Hubble's View of NGC 4911

This week’s OOTW features an OOTD by Alice written on Thursday 12th of August.

With a redshift of 0.027 this spiral galaxy lies 320 million light years away from us. It’s NGC 4911, a spiral galaxy in the Coma Cluster; a city of galaxies gravitationally bound to each other in the constellation Coma Berenices. LEDA 83751 – the larger elliptical overlapping the galaxy – is actually sat in front of the spiral, which isn’t the best situation for overlap hunters:

Overlapping galaxies are especially useful to Bill and other astronomers interested in dust – the background galaxy acts like a torch, showing what the dust is doing in the former one. The best situation is an elliptical being further away than a spiral, since spirals tend to be dustier and more interesting. Sadly this pair appears to have the bad manners to be the other way round. How rude :D.

– A quote from Alice’s OOTD.

A new Hubble image of this galaxy has been released showing in more detail the huge amount of star formation going on nearer to the nucleus of the galaxy, the dust lanes streaking their way around the beginning of its spiral arms, and the wispy spiral structures wrapping their arms around the bustling galactic centre.

Peas Through a Lens

This week’s OOTW features today’s OOTD by Budgieye.

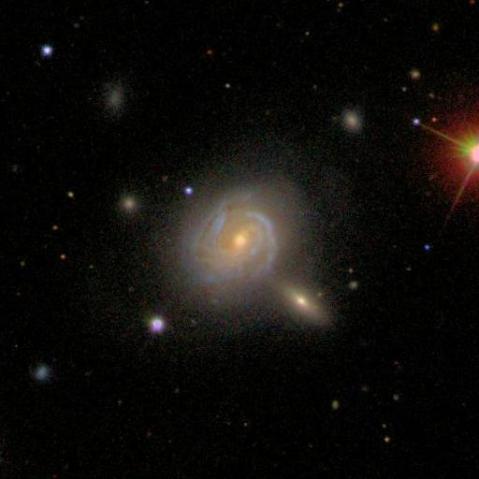

SDSS view of SDSS J001340.21+152312.0

This yellow fuzzy galaxy is a Quasar 1.59 billion light years away from Earth in the constellation Pegasus; it’s just above to the left of the star Gamma Pegasi.

When you zoom in with the Keck observatory you’re treated to this beauty:

Now what the Keck telescope can see and the Sloan telescope can’t are the two red smudges in the blue glow of the Quasar. These smudges are in fact one Pea gravitationally lensed by the QSO sitting in front of it! This is the first ever example of a Quasar strongly lensing an object. This is where a galaxy or a cluster of galaxies are so massive that they bend space-time so much that it visibly bends light around them. So the light emitted by an object sitting behind a cluster of galaxies gets bent around the cluster, creating multiple images of one object.

So how can we tell they are multiple images of the same object?

A quote from Budieye’s OOTD:

To ensure that the two red objects on each side of the quasar is actually the same object, each object must have their spectrum taken separately.

Both blobs of red light had identical spectra, indicating that both blobs are the same object, and that the quasar is bending the light from the distant galaxy into two blobs.

Me, HST and the history of surveys

Before I start with a new series of posts, please let me introduce myself.

My name is Boris Häußler (look at my horribly out-of-date website here). I am German but currently working as a research fellow in Nottingham, UK, where I have just recently started my second postdoc with Steven Bamford, whom many people here may know. I have spent the last years (actually, my whole scientific life so far) working on Hubble Space Telescope (HST) data, mainly on the GEMS and STAGES surveys, and have gathered particular experience in the field of galaxy profile fitting, trying to measure sizes, shapes, etc. of distant galaxies. Whereas my previous projects have mainly been working on galaxies at redshift z~0.7, my new job is trying to do similar and more advanced things on more local galaxies, mainly SDSS galaxies, which of course everyone familiar with Galaxy Zoo will know as these are the galaxies classified in both Galaxy Zoo and Galaxy Zoo 2. Initially, one would think that this is a much easier job to do, but as this data is from ground-based telescopes, it proves to be challenging.

This brings me to an interesting position. Although Galaxy Zoo is not my primary science project, I am now connected to the survey through Steven, our galaxy sample and (for now) more directly through this blog. Having worked on HST galaxies for ages, it is of course very interesting for me to see these galaxies now being classified in Galaxy Zoo: Hubble. Having created some of the colour images that both GEMS and STAGES have used for outreach purposes, I have looked at thousands of these galaxies myself and know how stunningly beautiful they can be. I very often got lost on our images, simply browsing around and being fasctinated by the variety of the galaxies. At least in GEMS I know many galaxies by heart and could possibly directly point you to at least some of the brighter and/or more interesting galaxies.

This brings me to an interesting position. Although Galaxy Zoo is not my primary science project, I am now connected to the survey through Steven, our galaxy sample and (for now) more directly through this blog. Having worked on HST galaxies for ages, it is of course very interesting for me to see these galaxies now being classified in Galaxy Zoo: Hubble. Having created some of the colour images that both GEMS and STAGES have used for outreach purposes, I have looked at thousands of these galaxies myself and know how stunningly beautiful they can be. I very often got lost on our images, simply browsing around and being fasctinated by the variety of the galaxies. At least in GEMS I know many galaxies by heart and could possibly directly point you to at least some of the brighter and/or more interesting galaxies.

Being kind of an HST expert, Steven has asked if I would want to write a series of posts about HST, an offer that I found hard to turn down, so I’ve decided to write quite a long series about the HST, its history, its future and especially introducing some of the bigger HST surveys, some of which of course build the content of Galaxy Zoo: Hubble now. But before I write and post all this, I would be interested to know what people would actually want to know about Hubble and everything connected with it. So if you have any comments, any wishes, any questions, please post them below and I will try to answer them in the future.

My current plan for the next months contains the following posts, roughly running through the history of Hubble in chronological order:

- Who is Edwin Hubble, the man that gave HST it’s name?

- History of Hubble, the planning and the start 20 years ago

- HST gets spectacles, first service mission

- HDF, the Hubble Deep Field, the first famous survey,

- Another service mission, putting new cameras (e.g. ACS) on HST

- GOODS, the Great Observatories Origins Deep Survey

- GEMS, Galaxy Evolution from Morphologies and SED

- AEGIS , the Deep Extragalactic Evolutionary survey

- HUDF, the Hubble Ultra Deep Survey, the deepest survey ever made

- STAGES, Space Telescope Abell901/902 Galaxy Evolution Survey

- COSMOS, the Cosmic Evolution survey

- The service mission to put in another camera (WFC3)

- Upcoming surveys: CANDELS

- The Future of HST

- HST’s successor, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)

If you want to know about anything else, please let me know below.

Thanks and Cheers for now,

Boris

Supernova updates

Hello from the William Herschel Telescope, where I’m observing some of those lovely supernova candidates that have been pouring out of The Supernova Zoo lately.

It’s been a while since our last update. We’ve been running supernova zoo in a very serious way now for several months, and, after ironing out a few little bugs and adding some improvements, the zoo is making a massive contribution to the supernova identification effort in The Palomar Transient Factory. The zoo has already classified some 20,000 supernova candidates, usually several hundred every day; it’s a fabulous effort. You’ve classified every supernova candidate that we’ve put in the zoo!

We also hope that you’re beginning to see feedback on the supernova candidates that you spend your time classifying (at least the better ones!). From this current observing run I’ve been adding comments as I classify the events that you’ve highlighted, so you might see them appearing in your “MySN” area (of course, the more you classify, the more likely this is to happen!).

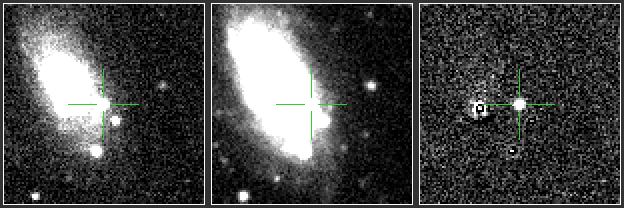

Here are some of your nice recent finds, all Type Ia Supernovae.

This one seems to live in a galaxy located in a cluster of galaxies:

This is one in a nearby NGC galaxy – the SN is located directly in one of the spiral arms.

And this one is also in a spiral galaxy – but one that is more edge on:

We’re currently preparing a scientific publication that will detail supernova zoo and how it works – and we also have plans to add a new survey to give you even more supernova to play with. So stay tuned!

OK, my exposure has just finished, so I’ll sign off here and go and see what the latest supernova candidate turned out to be!

— Mark

Galaxies spiralling out of control

Today’s OOTW features Alice’s OOTD, posted on the 29th of July.

AHZ40004wr from Hubble Zoo

This is AHZ40004wr, a galaxy residing in the constellation Taurus around 3 billion light years away. It’s a wonderful spiral galaxy, and following its spiral arms is a large dust lane, a place full of young stars and stars that are only just being formed.

AHZ40004wr by Swengineer

Zooite Swengineer gave us a wider view of AHZ40004wr and the surrounding galaxies by working with the FITS images and revealed the mess of galaxies above. The main spiral galaxy in the background is 2MASS J03324999-2734330, an X-ray source according to SIMBAD, and it is also around 3 billion light years away.

You can view more images of these galaxies here and here, and to work with the FITS files I recommend DS9 or Aladin, which I used to find the other galaxies details.

And to highlight a request from Alice’s OOTD, Alice would very much like to know if anyone could write any FITS and image editing tutorials on the galaxy zoo forum.

Zoo 1 data set free

Hi all

It’s taken longer than it should have done – more than three years since the launch of the site – but the data from the original galaxy zoo is now available.

The paper describing the data set was only accepted by the journal yesterday, but we were confident enough after an earlier report to go ahead and make it public. The data can also be downloaded in a variety of formats from our site, or via Casjobs.

The data set is slightly updated from our previous efforts; while we’ve been busy with Galaxy Zoo, the good people of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey produced a new data release which included more spectra, allowing us to estimate biases for more galaxies than ever before.

We’ve had a lot of fun exploring this data set, and we hope that by making it available to all other astronomers then they will make use of your classifications too.

Knowing the Zoo, I wouldn’t be too surprised to see something interesting come from any of you who wanted to have a play – feel free to download and dig in, and let us know how you get on. Meanwhile, the team are working hard on Zoo 2, and hopefully it won’t take as long before that data set too is ready to go.

The Sunflower of Canes Venatici

This galaxy is featured in LizPeter’s OOTD for 24th of July 2010.

M63 from the SDSS

This is Messier 63, though I much prefer its other name, the sunflower galaxy. It’s a wonderful dusty spiral galaxy lying 22.9 million light years away from Earth in the constellation Canes Venatici. It’s one of 7 galaxies bound gravitationally together in the M51 group, and according to Wikipedia, it is one of the first objects to be seen to have spiral arms. This was pointed out in 1845 by William Parsons in a time when these objects were thought to be ‘spiral nebulae’ in our own galaxy, and not galaxies themselves. SIMBAD also claims that there is a cluster of stars lying in the foreground of the galaxy.

There are some brilliant Hubble Legacy images and spectra here, and some more from assorted observatories here!

Observing Red Galaxies With VIRUS-P

Hi Zoo fans,

My name is Peter Yoachim and I’m currently a postdoc working in the Astronomy Department at the University of Texas in Austin.

I got involved with the Galaxy Zoo after I saw Karen’s paper on Red Spirals. When I first read the paper I thought, “Wow, that’s really cool, spirals shouldn’t look red like that, wonder what happened to those galaxies.”, followed shortly by, “OMG, we have the perfect instrument to make follow-up observations of these objects!”

While I’ve been at UT, I’ve been making extensive use of VIRUS-P (Visible Integral-field Replicable Unit Spectrograph Prototype), a new instrument at McDonald Observatory in West Texas. Right now, VIRUS-P is mounted on the 2.7m Harlan J. Smith telescope. While modest in size by current standards, the 2.7m has been a scientific workhorse since 1968 although it is probably most famous for having several bullet holes in the primary mirror.

As I tell my 101 students, images of the sky are a great starting point, but if you want to do Astrophysics, you need to observe some spectra. With galaxies, the full spectra can tell us how different parts of the galaxy are moving (via the redshift and blueshift of light), what kind of stars are in the galaxy, and if there is any hot gas present. VIRUS-P is great for getting spectra, especially for targets like nearby galaxies.

In the bad old days (like when I was doing my thesis work 6 years ago), it was common to pass light from the telescope through a narrow slit, then bounce it off a grating to disperse the light onto the detector to observe the spectrum. The problem is that the narrow slit blocks most of the light from the galaxy. This is a tragedy! That light traveled for (literally) millions of years only to bounce off the slit mask at the last second.

Rather than use a long slit, VIRUS-P uses a fiber-optic bundle to pipe the light around. Here’s an example from a recent paper. NGC 6155 is just a nice normal galaxy, here’s an image of it from the Sloan survey:

When I observe the same galaxy with VIRUS-P, I see this:

Each circle represents a fiber. I’ve color-coded the fibers so that the brightest spectra are blue and the faintest are red. This isn’t too fancy, it even looks quite a bit worse than the Sloan image. But look what happens if I calculate the velocity from the redshift of the spectra in each fiber:

Now we can see the rotation of the disk. The top left of the galaxy is moving away form us, while the bottom right is moving towards us. The redshift of light only shows us the part of the motion that happens to be along our line of sight, but that’s still enough to get a good idea of how the stars and gas in the galaxy orbit the center. The next trick is to add up the spectra from multiple fibers to build up the signal to make it possible to measure accurate ages for the stars.

What we see here is the center of the galaxy is old (~7 billion years), while the disk is young and still forming stars (average age ~4-6 billion years). The youngest section that’s 4 billion years old corresponds to the bright blue spiral arms in the Sloan image. The cool part is the very outskirts of the disk are made of very old stars (8-10 billion years old), a result some of my coauthors actually predicted.

It should be clear now how VIRUS-P will be great for observing the red spirals. We can compare the motions of red spiral disks to regular spirals, and we can measure stellar ages to try and determine when star formation shut off in these galaxies.

The observing of the red spirals has been done by intrepid UT graduate student John Jardel. With the remnants of hurricane Alex blowing through, the observatory has received excessive rain this summer. All that rain makes it hard to observe, plus it lets the rattlesnakes and scorpions thrive. Here’s a scorpion I caught in the observatory lodge last week:

Despite the weather and wildlife, John was able to observe 5 galaxies. We’ve just finished our last observing run of the season, so we haven’t had a chance to analyze the data yet. But looking at the raw images, we already see something interesting:

The horizontal stripes are the signal from each individual fiber. The bright vertical lines are emission lines from the earth’s atmosphere. The two circles show 5 fibers where we can see bright spots. Those spots are emission from hot Hydrogen gas in the galaxy. If there’s gas, it’s possible these red galaxies could start forming stars again and turn back to regular blue spirals. Since the gas is hot and in emission, it could even be the case that there is star formation going on right now.