We got Radio Observing Time

Observing Time Update from Ivy Wong:

The majority of the galaxies that we observe can be divided distinctly into 2 categories: star-forming spirals (late-types) and non-star-forming spheroidals (early-types). The purpose of my research is to study how one type of galaxies transform into the other. In a previous Zoo project, we studied a sample of local post-starburst galaxies— galaxies which have only recently stopped forming stars. Even though star formation has only recently ceased for these transition-type galaxies, they already have the same shape as that of non-star-forming galaxies.

To further investigate how the shape of a galaxy correlates with its colour (or star formation history), we now focus our efforts onto a sample of blue early-type galaxies (found by Zookeeper Kevin) which are thought to be the progenitors of the post-starburst galaxies. Blue early-types are unusual relative to regular early-types because they appear to still be forming stars. Why are they still forming stars? Did a recent interaction trigger this new wave of star formation ?

In other studies that I have made of nearby galaxies, I have found that studying the gas content (atomic hydrogen; HI) of galaxies is a good way of finding evidence for past interactions as well as a good way of finding galaxies which are still forming stars. This is because stars are formed from an initial reservoir of gas. The gas reservoir of a galaxy is highly sensitive to environmental effects and will show tell-tale features such as tidal tails and bridges which can point to external factors affecting the galaxy’s evolution.

We recently proposed for observing time to use the Westerbork Synthesis Radio Telescope (Netherlands) to map the HI content of a sample of 6 Northern blue early-types. It is extremely difficult to map HI because the emission comes from the spin-flip of the electron in the Hydrogen atom. We recently found out that we have gotten some non-guaranteed time to use the WSRT so in the event that all goes well, I hope to post some HI maps of these blue early-types.

Live Chat – Hangout with Us

2012 is turning out to be a great year for Galaxy Zoo science. From Voorwerpjes to mergers to barred galaxies, there is lots to talk about right now when it comes to Galaxy Zoo. Tomorrow afternoon we’ll be holding a live chat with Galaxy Zoo science team stars Chris Lintott and Karen Masters. Starting at 2pm British Summer Time (1300 UT, 9am in New York, 3pm in Paris), Chris and Karen will be answering your questions and talking about some of the recent Galaxy Zoo work, made possible why your efforts on galaxyzoo.org.

If you have anything you’d like to them to discuss, or any questions you’d like them answer, then please either leave a comment here or Tweet us @galaxyzoo. We’ll also take questions via Twitter during the live chat.

You can watch the live chat right here on the blog, via our YouTube channel, where the video will also be posted afterwards. We’ll put links here, as well as on Facebook and Twitter, nearer the time. We’ll be using Google Hangouts for the live chat, so you can add the Zooniverse’s Google+ page to your own Google+ circles and connect that way too.

UPDATE: The live chat will begin shortly. The video feed will be visible here nearer the time.

Multi-wavelength Viewer for Galaxy Zoo

Hi again,

We have the first tool in an alpha state online. The Multi-wavelength Viewer can be accessed at:

You will be able to visualize any SDSS galaxies that you classified in the current iteration of Galaxy Zoo. We provide all five filters of the galaxy (U, G, R, I, Z), and offer you tools to scale and stretch the pixels in this image. There is quite a large todo list for this tool, but feel free to ask questions and offer feedback.

Enjoy!

Amit

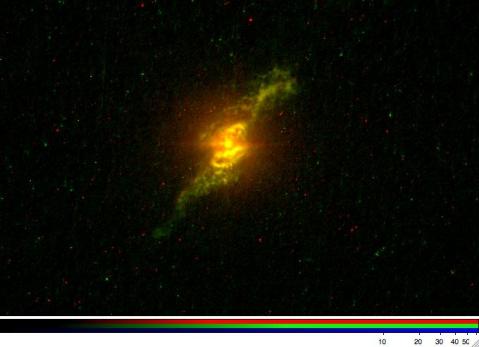

Curiouser and curiouser – Hubble and Mkn 1498

Fresh off the telescope, here’s a first view of the “Voorwerpje” gas clouds around the Seyfert galaxy Markarian 1498. Its nucleus, shown in our Lick and Kitt Peak spectra, is a type 1 Seyfert, meaning that we see the broad-line region of gas very close to the central black hole, moving at high velocity. Those data showed highly-ionized gas to a radius of at least 20 kiloparsecs (65,000 light-years). Its nucleus is too dim to account for the ionization of the extended gas clouds, which landed it a spot in our list of seven objects for the Hubble proposal. Getting these data now was an unexpected treat – they were originally scheduled to be taken next November. As another bonus, the good people at the Space Telescope Science Institute just last week implemented the software to deal with charge-transfer problems in the Advanced Camera CCDs, right in the pipeline, improving the image quality a lot (it took months to get to this point with the Hanny’s Voorwerp data). And here it is, Markarian 1498 in a combination of [O III] emission (green) and Hα (red):

This is… interesting. From the few of these galaxies where we have data so far, loops of ionized gas near the nucleus may be a recurring theme. I could add speculations on what we’re seeing in Mkn 1498 – but for now, I’ll just let everyone enjoy the spectacle.

My Galaxies – Write in Starlight

Long time Zookeeper Steven Bamford has made a new website on which you can easilly write any words you like from the galaxy alphabet.He’s called the website: My Galaxies – Write in Starlight!

Enjoy!

My favourite colour magnitude diagram

I was embarrassed to discover today that I never got around to writing a full blog post explaining our work studying the properties of the red spirals, as I promised way back in October 2009. Chris wrote a lovely post about it “Red Spirals at Night, Astronomers Delight“, and in my defense new science results from Zoo2, and a few other small (tiny people) things distracted me.

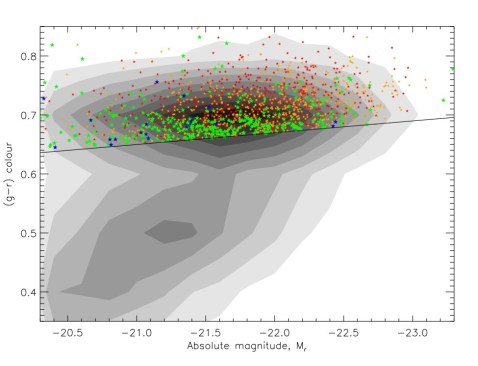

I won’t go back to explaining the whole thing again now, but one thing missing on the blog is the colour magnitude diagram which demonstrates how we shifted through thousands of galaxies (with your help) to find just 294 truly red, disc dominated and face-on spirals.

A colour magnitude diagram is one of the favourite plots of extragalactic astronomers these days. That’s because galaxies fall into two distinct regions on it which are linked to their evolution. You can see that in the grey scale contours below which is illustrating the location of all of the galaxies we started with from Galaxy Zoo. The plot shows astronomical colour up the y-axis (in this case (g-r) colour), with what astronomers call red being up and blue dow. Along the x-axis is absolute magnitude – or astronomers version of how luminous (how many stars effectively) the galaxy is. Bigger and brighter is to the right.

So you see the greyscale indicating a “red sequence” at the top, and a “blue cloud” at the bottom. In both cases brighter galaxies are redder.

The standard picture before Galaxy Zoo (ie. with small numbers of galaxies with morphological types) was that red sequence galaxies are ellipticals (or at least early-types) and you find spirals in the blue cloud. The coloured dots on this picture show the face-on spirals in the red sequence (above the line which we decided was a lower limit to be considered definitely on the red sequence). The different colours indicate how but the bulge is in the spiral galaxy – in the end we only included in the study the green and blue points which had small bulges, since we know the bulges of spiral galaxies are red. These 294 galaxies represented just 6% of spiral galaxies of their kind.

So this is one of my favourite versions of the colour magnitude diagram.

Lens Zoo is Coming!

We’re very pleased to tell you that we’ve been awarded developer time from the Citizen Science Alliance to build a new, exciting Zooniverse project to discover gravitational lenses.

What’s a gravitational lens, you might ask? When a massive galaxy or cluster of galaxies lies right in front of a more distant galaxy, the light from the background source gets deflected and focused towards us. These space-bending massive galaxies allow us to peer into the distant Universe at around 10x magnification, and to make accurate measurements of the total (dark and luminous) mass of galaxies.

As many of you know, there has been a long-running and enthusiastic search for lenses in the “weird and wonderful” part of the forum; although lens-finding was never a goal of the Galaxy Zoo project, this forum has turned up some interesting systems which we are still following up. Up until now, the GZ lens search has been quite informal: it has not been easy keeping track of all the candidates that have been suggested! Nevertheless, the Lens Hunters have done an amazing job, collecting and filtering the suggestions as they come in, and teaching themselves and each other about the astrophysics of lensing.

Impressive stuff: enough to persuade a group of professional astronomers that a specially-designed Zoo for identifying lenses could be a powerful way of analyzing the new wide-field imaging surveys that are coming online. In this Lens Zoo we will be able to provide you with new tools – designed, we hope, with you – to find new lenses more effectively. We have teamed up with astronomers from several big surveys who are eager to harness your citizen science power, and will be providing a lot of new, high quality data to be inspected. Over the next 6-10 months we’ll be working hard with the Zooniverse developers to build the Lens Zoo, and we hope you will join us for the ride: Lens Zoo needs you!

Phil, Aprajita, Anupreeta & the Lens Zoo team.

A first Hubble look at UGC 7342

Overnight, Hubble got our first data on perhaps the most spectacular Voorwerpje host galaxy, the merging system UGC 7342. We have to wait until almost the end of the year for what we really wanted to see, the ionized gas. The telescope has particular time pressure in some parts of the sky (as if it doesn’t have extreme time pressure on everything people want to do with it), so we split the two sets of images to fit the schedule better. This time, we got data in WFC3 for two medium-width filters in the orange and deep red, selected to be essentially blind to emission from the gas. These will be used to subtract the contribution of starlight from the gas images, so we can analyze the gas properties cleanly. The emission-line images use the older ACS camera, which has a set of tunable filters which can isolate any optical wavelength we need. They come at year’s end, because we have to specify a particular range of orientation angle of the telescope to fit all the gas in their 40×80-arcsecond filter field. That, plus the requirement that the solar arrays can face the Sun directly, gives us a restricted time window.

As a reminder, here’s UGC 7342 from the SDSS data.

And here is a first look at the Hubble images, warts and all. With only the two filters in orange and deep red, the color information we get is pretty muted. Here’s the whole galaxy, shrunk 4 times from the original pixel scale to fit:

This show the companion and tidal streamers of stars. UGC 7342 itself shows shells of stars, which can be formed when a lower-mass disk galaxies merges with a more massive elliptical. With some additional velocity information, those might be able to give a time since the merger (with some tailored simulations). The elliptical reflections are from bright foreground stars outside this trimmed view; the emission-line images will at least have these in different places, using a different camera and different telescope orientation.

Zooming in 4 times to the nucleus shows that UGC 7342 has complex dust lanes crossing in front of the core. These are perpendicular to the directions where we see that distant gas is ionized by radiation from the nucleus, which is pretty common. The fact that the dust (and almost certainly associated gas) wraps at right angles to most of the structure in the galaxy is another indication that a merger took place recently enough that the situation hasn’t settled down into a long-lasting remnant.

Next up? The scheduling windows for SDSS 1510+07, NGC 5972, and the Teacup AGN all happen in overlapping spans from June to August. Bring on the bits!

Beautiful galaxy Messier 106

Inspired by today’s Astronomy Picture of the Day Image, here’s a quick post about the beautiful nearby spiral galaxy, Messier 106 (or NGC 4258).

|

| M106 Close Up (from APOD) Credit: Composite Image Data – Hubble Legacy Archive; Adrian Zsilavec, Michelle Qualls, Adam Block / NOAO / AURA / NSF Processing – André van der Hoeven |

This is a composite Hubble Space Telescope and ground based (from NOAO) image. The ground based image was used to add colour to the high resolution single filter (ie. black and white) image from HST.

M106 has traditionally been classified as an unbarred Sb galaxies (although some astronomers claim a weak bar). In the 1960s it was discovered that if you look at M106 in radio and X-ray two additional “ghostly arms” appear, almost at right angles to the optical arms. These are explained as gas being shock heated by jets coming out of the central supermassive black hole (see Spitzer press release).

Messier 106 (or NGC 4258) is an extremely important galaxy for astronomers, due to it’s role in tying down the extragalactic distance scale. A search in the NASA Extragalactic Database (NED) will reveal this galaxy has 55 separate estimates of its distance, using many of the classic methods on the Cosmic distance ladder. Most importantly, M106 was the first galaxy to have an geometric distance measure using a new method which tracked the orbits of clumps of gas moving around the supermassive black hole in its centre. This remains one of the most accurate extragalactic distances ever measured with only a 4% error (7.2+/-0.3 Mpc, or 22+/-1 million light years). The error can be so low, because the number of assumptions is small (it’s based on our knowledge of gravity), and as a geometrically estimated distance it leap frogs the lower rungs of the distance ladder.

This result was published in Nature in 1999: A geometric distance to the galaxy NGC4258 from orbital motions in a nuclear gas disk, Hernstein et al. 1999 (link includes an open access copy on the ArXiV).

Because M106 has so many different distances estimated using so many different methods, and is anchored by the extremely accurate geometric distance, it helps us to calibrate the distances to many other galaxies. Almost all cosmological results, and any result looking at the masses, or physical sizes of galaxies need a distance estimate.

So M106 is not only beautiful, it’s important.