Zoo 1 data set free

Hi all

It’s taken longer than it should have done – more than three years since the launch of the site – but the data from the original galaxy zoo is now available.

The paper describing the data set was only accepted by the journal yesterday, but we were confident enough after an earlier report to go ahead and make it public. The data can also be downloaded in a variety of formats from our site, or via Casjobs.

The data set is slightly updated from our previous efforts; while we’ve been busy with Galaxy Zoo, the good people of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey produced a new data release which included more spectra, allowing us to estimate biases for more galaxies than ever before.

We’ve had a lot of fun exploring this data set, and we hope that by making it available to all other astronomers then they will make use of your classifications too.

Knowing the Zoo, I wouldn’t be too surprised to see something interesting come from any of you who wanted to have a play – feel free to download and dig in, and let us know how you get on. Meanwhile, the team are working hard on Zoo 2, and hopefully it won’t take as long before that data set too is ready to go.

Machine Learning Paper Accepted!

Exciting News from Manda Banerji on the Machine Learning paper:

Hi Everyone!

This is to let you all know that the Galaxy Zoo machine learning paper has now been accepted for publication in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society journal. The final version of the paper is at http://arxiv.org/abs/0908.2033. You can read all about the paper in my previous blog post at http://blogs.zooniverse.org/galaxyzoo/2009/08/05/latest-galaxy-zoo-paper-submitted/.

The paper has already attracted a lot of interest from the computer science community demonstrating that your classifications are proving useful and interesting to non astronomers as well!

Zoo 2 Bars Paper Available Now

There’s been a lot of interest in the Galaxy Zoo 2 bars paper since I posted about its submission last month. So this is just a quick note to say we decided to make it available on astroph where you can read about the results in full.

Red spirals at night, astronomers' delight

We heard a few days ago that our paper on red spirals has been accepted by the journal. Not only is this another success for Galaxy Zoo science, but it’s a tribute to the hard work of Karen who led the effort. What with the first Zoo 2 paper being submitted and a few other distractions as well it’s been a very busy week for her.

The paper itself is another variation on what should be becoming a very familiar theme for those who have followed Galaxy Zoo science: colour and shape are not the same, and tell us different things. To recap slightly, as young, massive and short-lived stars are blue, colour is a measure of what’s happened recently. The blue spiral arms in the galaxy pictured below, for example, mark sites of recent star formation.

It was known long before Galaxy Zoo that most of the star formation in our local Universe takes place in spiral galaxies, and so they tend to be blue whereas ellipticals are often red. In looking at the blue ellipticals and now the red spirals, it’s clear that interesting things happen when this rule is broken.

Before we can work out what’s going on though, we have to find our red spirals, and this is trickier than it sounds. If we weren’t careful, then our sample would get contaminated by edge-on systems, which appear redder because of the effect of the dust that scatters light which travels through the disk. As this paper uses only Zoo 1 data, we just selected the roundest spirals assuming that this would get rid of those pesky edge-on systems; we also insist that Zooites were able to identify a direction to the spiral arms.

It turns out that 6% of spiral galaxies are red, which I think is higher than most would have guessed before this project. So how did a substantial number of spiral galaxies come to turn red? What caused them to cease forming stars and become what the paper title calls them : ‘Passive red spirals’?

One important clue is understanding where this process happens. It turns out that the greater the density of the environment a spiral finds itself in (that is, the more neighbours it has) the more likely it is to be red…but only up to a point. Once we find ourselves near the core of a cluster of galaxies, the number and fraction of red spirals drops dramatically. So whatever it is that is causing the spirals to turn red must be more likely in the outskirts of galaxy clusters, but relatively rare outside this particular environment.

The story is, as ever, a little more complicated than that. If it was the environment that was driving the dramatic change from blue to red, then we’d expect the properties of the red spirals to depend on the environment. We might find that those in the densest environments were redder than their (still quite red) counterparts further out, for example. But we don’t. We don’t see any connection between the properties of the red spiral and the environment they find themselves in.

In my next blog, I’ll look at what we do know about this mysterious population of galaxies unearthed by your hard work. Until then, if you want the gory details, you can find the latest version of the paper over here.

First Results from Galaxy Zoo 2: Bars in Disk Galaxies

I’m happy to announce that the first paper using Galaxy Zoo 2 data was submitted (to MNRAS) yesterday.

In this work we used an early look at the information you have provided us on the presence of bars in a sample of GZ2 galaxies too look at trends of the bar fraction (basically how likely a certain type of disk galaxy is to have a bar) as a function of other properties.

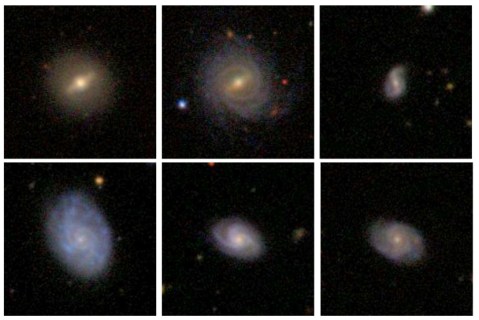

Examples of barred (top) and unbarred (bottom) galaxies from Galaxy Zoo 2.

In doing this research I’ve learned that bars are really interesting features in disk galaxies. Unlike spiral arms, which are density waves (meaning stars pass in and out of them over the life of the galaxy), the matter in bars (stars and gas etc) actually rotates with the bar. This means that the bar breaks the symmetry of the disk of the galaxy and causes transfer of material both in an outwards along its length. What it boils down to is that bars should have a significant impact on the internal evolution of a galaxy. They have been suggested as a way to build some types of bulges, as a way to fuel star formation in the central regions, and perhaps even fuel AGNs. At the outer ends, the bar can induce ring like structures (see the top middle example) – and might even be responsible for driving spiral structure.

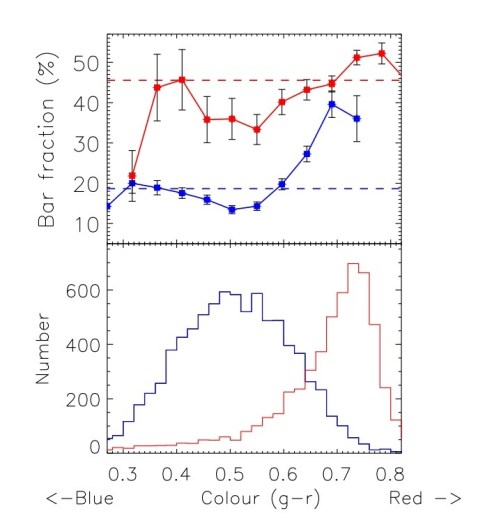

So what did we find? Well we observed a strong correlation between the bar fraction and the colour of the disk galaxy. Redder disk galaxies are much more likely to have bars identified by GZ2 users than bluer disk galaxies.

Bar fraction as a function of galaxy colour. The dashed line shows the overall bar fraction for the whole sample.

We also tried to split the sample by the size of the bulge. We find that disks with large bulges (shown by the red line below) have high bar fractions, and that disks with small bulges (shown by the blue line) have low bar fractions. This split by bulge size also splits the disks into things which are mostly red (large bulge) and blue (small bulge) – as illustrated by the histograms of the colour distribution of the two types of disk galaxies. What’s new here is that we show this also correlates strongly with the presence of a bar.

Top: bar fraction as a function of galaxy colour split into disk galaxies with large bulges (red) and small bulges (blue). The dashed line shows the overall bar fraction for each sub-sample. Bottom: histograms showing the colour distribution of the disk galaxies with large bulges (red) and small bulges (blue).

So we seem to split disk galaxies into two populations – ones that are red, have large bulges and are very likely to have bars, and ones that are blue, have small bulges, and are not so likely to have bars.

This gives an overall picture in which bars may be very important to the evolution of disk galaxies – perhaps more so than has been thought before. It’s very interesting, and I look forward to spending more time with barred galaxies and with the rich data set that you have given us with Galaxy Zoo 2.

We’re already working on more results from the bars using Galaxy Zoo 2, so expect updates soon. Also I just saw some very interesting results on bar lengths using data from the (now completed) Bar Drawing project. Hopefully we’ll have a paper from that soon too. Stay tuned!

How to find black holes?

The first step in trying to understand the connection between black holes and galaxies is finding them. But black holes are, well, black. In fact, you might say their blackness is their most defining feature.

So, how do you find them? It turns out that when they’re feeding on infalling gas and dust, a massive black hole can turn into the brightest object known in the whole universe – a quasar!

As the gas and dust falls towards the black hole, it settles into a disk around it, and as it moves in, friction in the disk heats up all the matter in it to such temperatures that it stats shining. In this way, black holes can be very bright, or quite dim, depending in part on how much matter they are munching on.

There are many ways to find feeding black holes and for the Galaxy Zoo paper on black hole growth, we used the emission lines that AGN (active galactic nuclei, or feeding black holes) cause when the light coming from the accretion disk shines on some other gas floating around in the host galaxy and makes that light in turn emit light with a very particular signature that we can detect by carefully analysing the spectra.

Black holes – why do galaxies care, anyway?

Now that our paper on AGN host galaxies (galaxies whose black holes are feeding) is out, I will write a few blog posts about what we found with your help. But before we start, a little background.

Why do black holes matter? We now believe that at the centers of most, if not all galaxies, there is a supermassive black hole. We call these black holes “supermassive” to distinguish them from stellar mass black holes that were formed in the deaths of massive stars. These supermassive black hole can be as heavy as a million or even a billion solar masses.

So you might think that these enormous black holes can wreak havoc in their host galaxies. However, galaxies are even bigger, much bigger than these black holes. In general, the black hole makes up about 0.1% of the mass of its host galaxy making really just a drop in the bucket.

In fact, their gravitational sphere of influence is tiny compared to the size of the whole galaxy and so they generally don’t affect anything but their immediate surroundings. As far as the galaxy as a whole is concerned, the supermassive black hole at its center might as well not be there.

But why is the mass of the black hole always some fraction of the galaxy mass (or to be more precise, bulge mass)? How does the black hole even know how big the galaxy is? Why does the mass of the black hole correlate with the mass of the galaxy bulge (the M-sigma relation)? It’s almost as if they somehow grew together….

Galaxy Zoo paper on AGN host galaxies accepted!

Dear all,

I am happy to tell you that after a lot of work and a long peer review process, the Galaxy Zoo paper on AGN host galaxies (galaxies whose supermassive black holes are feeding) has finally been accepted by the Astrophysical Journal.

I’ve blogged about it before when we submitted it last year. The paper itself has gotten a lot longer than I initially thought it would be because the morphologies we got out of all your clicks revealed quite a few things that we really didn’t expect, and that we weren’t sure how to explain. I’ll keep this blog post short, but I’ll try and follow it up with more details on what your clicks enabled us to to find, and (maybe also) what it means about growing black holes and how they affect the galaxies that they live in.

One of the more interesting things we found were these galaxies whose black holes are growing. In many ways, these galaxies resemble our own Milky Way…

In the meantime, you can get a PDF copy of the paper here, or off astro-ph when it appears there tomorrow night (January 19th).

Galaxy Zoo: Dust in Spirals – accepted to MNRAS

My Galaxy Zoo paper on the dust content of spiral galaxies was accepted for publication in the Monthly Notice of the Royal Astronomical Society this morning, and will be available here on the ArXiV server after 1am GMT tomorrow (Wed 13th Jan 2010).

You can read about the work that went into this paper and our main results in my previous blog posts on its submission, about a scientific poster on the work, and finally my very first blog post here: “Blue Skies and Red Spirals”.

Happy reading, and thanks again for all the spirals!

Galaxy Zoo Red Spiral Paper Submitted

Just a quick post to let you all know that earlier this week I submitted (to MNRAS) a paper on the Galaxy Zoo Red Spirals.

We decided to make this paper available right away on the arXiV, so you can download it here

This paper has been in the works for quite some time (remember the BBC press about Galaxy Zoo red spirals), and I’m happy to have been able to contribute to finishing it and finally getting it submitted. I should particularly mention the work of Sussex/Leiden student, Moein Mosleh who did a lot of the analysis, and of course it’s related to the Galaxy Zoo papers by Steven Bamford and Ramin Skibba who both talk about the environmental dependence of red spirals (ie. where in the universe they like to live).

I promise a post soon with a clearer explanation of what we did in this paper and the exciting results we found.