Galaxy Zoo 2 Author Poster

We’ve been meaning to do this for a while now and the Zooniverse Advent Calendar gives us the perfect excuse: the Galaxy Zoo 2 author poster. The poster shows the Sombrero Galaxy (M104) made up of the 51,000 names of Galaxy Zoo 2 volunteers who gave permission for us to display their names. Every person named on this poster has classified at least one galaxy and thus been a part of Zooniverse history.

You can download the smaller version (6.5MB) or the larger 7000 pixel version (25MB). You can take these posters and do what you like with them – print them, create wallpapers etc. You can also access the full list of names at http://zoo2.galaxyzoo.org/authors if you want to get a better look at the list.

If you do anything fun with these images or data, then please get in touch and share it via the comments section below.

UPDATE: Thanks to some eagle-eyed users we noticed that we were missing a few names (about 16,000!) so the poster has been updated. The Galaxy Zoo 2 Authors page will be update tomorrow. Sorry for the mix up but I think we have it right now.

An Extra-galactic Halloween

At a pumpkin carving event yesterday, we (a group of people from Yale astro) tried to come up with an appropriate theme for our pumpkin. Naturally, we decided on the Hubble Sequence of galaxy morphology:

Elliptical

Lenticular

Early Spiral

Late Spiral

Irregular

And the artists…

John Huchra

I’m going to take a little time to tell you about John Huchra and even if his name isn’t familiar yet, I hope you’ll understand why when I’m done. I don’t think anyone would disagree with me when I say that John Huchra (1948-2010) was a great astronomer, and a great man. His impact is felt in many areas of extragalactic astronomy, but in particular he leaves an immense legacy in our progress in mapping the universe.

John Huchra (2005)

In the 1980s, John (working with his collaborator Margaret Geller and others) published a new map of part of the universe (see below). John was an enthusiastic observer, and much of the data in the below figure comes from his long nights at the telescope. What the below shows is the position of galaxies in a slice from 8h-17h in right ascension and between 26.5-32.5 degrees in declination (a long and skinny strip which starts near “the twin stars” in Gemini and passes through Coma and Bootes ending in Hercules). In this strip galaxies are then spread out according to their redshift which because of Hubble’s Law acts as a proxy for distance.

The below image became famous because of the so-called CfA Stick Man (CfA after the Center for Astrophysics where the work was done). This “stick man” indicates the position of the Coma cluster (in the Coma constellation) where there is a large collection of galaxies, and where redshifts no longer equate so well to distance because of the large motions of the galaxies around the centre of mass of the cluster. This means in a redshift plot, all the galaxies get spread out in along the line of sight, and in this particular map end up looking like a stick man!

Distribution of galaxies in the CfA Redshift Survey

For astronomers this diagram showed conclusively that galaxies were not distributed randomly in the universe, and led to a complete revision of the way astronomers thought about the formation of galaxies. John and his collaborators got it absolutely right in their abstract which ended “These data might be the basis for a new picture of the galaxy and cluster distributions.”

John never stopped mapping the universe, and one of his passions was for measuring galaxy redshifts. For a most of his career this was a painstaking and time consuming process of taking spectra after spectra of single galaxies. But this process was clearly something John loved (as you can see for yourself if you ever find a copy of “So Many Galaxies, So Little Time” which is unfortunately not yet on YouTube!).

In fact John’s legacy in this area is not quite finished. He has a continuing program (The 2MASS Redshift Survey) on the CfA’s Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory in Arizona to measure redshifts for all galaxies in 2MASS (an all-sky survey in the near infra-red) to a fixed brightness limit (just over 40,000 galaxies in total) which just needs a handful more observations to be complete. John was also involved in some of the more modern galaxy redshift surveys, which use multi-object spectrograph (instruments which can take spectra of many galaxies at once) – especially the 6dFGRS (6dF galaxy redshift survey) in the southern sky (which is the southern part of the 2MASS redshift survey).

Along with redshifts, John was very interested in measuring direct distances to galaxies and pinning down the value of the Hubble Constant (the scaling factor between redshift and distance in Hubble’s Law). He was involved in the famous Hubble Key Project which measured H0 to 10% accuracy. The below picture shows many of the people involved in that project at the meeting where it was initiated.

John (kneeling) in 1985 at a meeting on the Cosmic Distance Scale at the Aspen Center for Physics.

John kept track of all published determinations of the Hubble Constant, and the below figure was posted on his office door at CfA showing the many published determinations of H0 since 1920 (based on data in his publicly available file hubbleplot.dat which you might notice is up-to-date until mid-2010).

Published values of the Hubble Constant

He also has a more complete History of the Hubble Constant, which explains all of this and is well worth a read.

I had the honour and privilige to work with John Huchra during my postdoctoral appointment at Harvard (2005-2008). I was hired to work on the 2MASS Redshift Survey, and ended up initiating a program to measure distances to some of the brighter spirals in it (using a relationship between how fast spirals rotate and how bright they are). I was working at Harvard when I first learned about the Galaxy Zoo project (from the BBC press at its first release). John and I did discuss Galaxy Zoo and it was definitely something he was interested in. In fact, many of the “professional” morphological classifications you can find (for example published in the NASA Extragalactic Database) come from John, and while I was at Harvard he was working on completing his personal morphological classification of the brightest half of the 2MASS Redshift Survey (roughly 20,000 galaxies). He just liked looking at galaxies I think.

John’s contributions to astronomy are immense. A search for his publications in the online database ADS will tell you that over his 40 year career he was involved in more than 700 papers, with a combined number of over 30,000 citations. Many of these papers are with students and postdocs he mentored, and he leaves a massive contribution in this area too – mentoring not only those who formerly worked with him, but so many others informally at conferences and meetings. John always had time for a chat.

John Huchra died on 8th October 2010. His death seemed sudden and unexpected to many in the astronomical community, perhaps because John was extremely visible right up until his death. He had only just stopped being the President of the American Astronomical Society, and had participated heavily in the US Decadal Survey (ASTRO 2010).

John had however had serious heart problems following a heart attack in 2006, and it seems had personally known his days were numbered. I like to believe he made a conscious choice to remain working in the field he loved, while enjoying his remaining time with his wife and teenage son. It will never have been enough time, and his loss (both personally, and to the field of astronomy) is deeply felt.

John is remembered in obituaries in The New York Times, and The Telegraph, as well as blogs from Cosmic Variance, and The Bad Astronomer, and Astronomy Now

He has a short autobiography on his website where you can read about him in his own words circa 1999. The rest of his website is also a treasure trove of useful information and links.

John, by definition, we’ll miss you.

Black hole hunter finds quarry!

The care and feeding of black holes in galaxies has been a major focus of Zookeeper Kevin’s work. Checking his research publications shows at least a dozen journal papers dealing with black holes, whether seen actively accreting and shining as active galactic nuclei, or lurking quietly in less spectacular galaxies. Now I can reveal that, thanks to new technology, black hole hunting has become dramatically easier. Witness this documentation from a site visit – only one building over from Kevin’s office. I didn’t see what kind of delivery vehicle this needed.

Comic moments with Hanny's Voorwerp and Galaxy Zoo

Time flies. A week ago, I was still running madly around to make sure everything was ready for a trip to Dragon*Con in Atlanta. FireWire cable, cooler for drinks in room, bag full of snacks, lab coat and Einstein wig to be taken seriously as a scientist, big posters of comic pages, PowerPoints for solo talks – check! What is Dragon*Con, anyway? A long holiday weekend with tens of thousands of people gathered to celebrate science fiction, fantasy, science and space exploration, robot building, costuming from all places and times, in our Universe an those so far only imagined. It has developed a reputation for being organized from the ground up, driven more by what the attendees want to see rather than what production companies wan to show. Therefore, it has fit nicely for Galaxy Zoo to have a presence here for the last several years.

These factors made this the perfect venue to host an event marking the launch of the Hanny’s Voorwerp webcomic. As part of the Space Track programming (one of about 25 simultaneous topics available a the Con), a ballroom at the Atlanta Hilton hotel was booked last Friday night at 10 p.m. At Dragon*Con, this is pretty much prime time, since so many attendees keep either astronomers’ or vampires’ hours. Pamela had the printed comic shipped directly there; much relief was expressed when they arrived with a day to spare.

The event opened with live music by the inimitable George Hrab. Among his selections was the Monty Python Galaxy Song; a later selection had lyrics customized for the occasion. Pamela introduced the proceedings, and asked how many people in the audience had ever classified for the Zoo. I counted 23. In fact, I asked this question for all the science talks I did, including panel discussion on the science of Avatar and Firefly. Every time, there were Zooites listening. You can see some of Pamela’s introduction in video edited by someone from the Skeptics Track here, about 4 minutes into the clip.

I spent a few minutes discussing the discovery and scientific followup of Hanny’s Voorwerp. After that, Hanny appeared on screen, Skyping in from Heerlen (and looking extraordinarily awake and chipper for it being 4 a.m. Saturday). For that connection from my laptop, and the UStream coverage, we have Pamela’s little Verizon wireless gizmo to thank – it made the connection via cell-phone network and turned that into a local wireless network, bailing us out when the hotel network wouldn’t quite do it in that room.

After Hanny’s remarks, we passed out the printed comics to the audience, while George Hrab entertained them again. The comic artists, Elea Braasch and Chris Spangler, were in attendance, and the audience had questions about their work and about how strange it was dealing with scientists. Perhaps not so oddly for this age and this project, this was the first time I actually met them.

The event finished off with some of the science programs’ trademark ice cream, made quickly from scratch with the help of liquid nitrogen. We gave away three of the big posters I had brought along as door prizes – I couldn’t bear to part with the fourth, showing Hubble peering past the central black hole in IC 2497, and brought it back for my office. There were also some “door prizes” for UStream viewers, randomly selected.

Meanwhile, for everyone who couldn’t be there, the whole comic can be seen online in several formats here.

Win a Signed Comic Book

With the launch of the comic ‘Hanny and the mystery of the Voorwerp’, we’re also launching a competition. So here’s your chance to win a copy of the book, signed by Hanny!

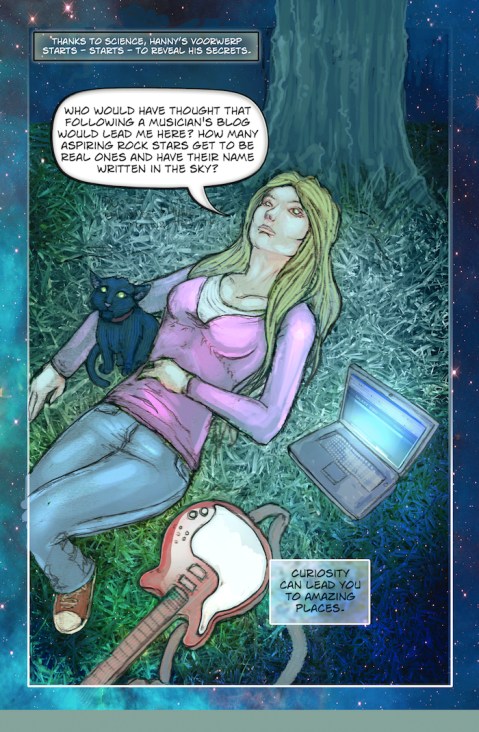

What you need to do: take a good look at the page published below – it’s one of the pages from the comic – and answer the following question: This scene might have happened in the real world as well as the comic – except for one thing. What is it?

All answers (serious and/or creative) can be sent in by commenting on this blog. (Note that the first set of books will have this page in it, but the improved page is already ready to be seen by the world too.)

Good luck!

"Hanny and the Mystery of the Voorwerp" goes live!

Here we are again, representing Galaxy Zoo at Dragon*Con. This is an enormous gathering of science-fiction and fantasy fans, aficionados of science, gaming, costuming, offbeat music – all packed into downtown Atlanta’s five largest conference hotels, every Labor Day holiday weekend. It’s a huge Con – the number of people here at one time or another during last year’s event was nearly one-quarter of the total number of people who have ever signed up for the Zooniverse projects.

An earlier post told of our presentations in a citizen-science panel in 2008. This year, we’re more deeply involved in several themes represented by attendees – astronomy, citizen science, writing, art, and comics. I refer, of course, to the (web)comic Hanny and the mystery of the Voorwerp, which will be released at a launch event Friday night. (Data from several satellites, including the Hubble Space Telescope, are involved, so of course we would start it with a launch). This is a public-outreach project funded by NASA, through the Space Telescope Science Institute, telling the story first of Hanny’s discovery of the Voorwerp, and then of the efforts of many of us to find out what it is and what makes it shine. Pamela Gay, who has been part of the Zoo education team for several years and is well known as a pioneer in using electronic “new media” to communicate science, took the leading role in organizing the project.

In true Zoo style, the writing of the script was a collaborative effort, carried out at the CONvergence meeting in Minneapolis. Under the watchful eye of fact-and-fiction author Kelly McCullough, the story took shape with a cast mostly composed of interested volunteers attracted by the opportunity. Things then sped up – we had to make the deadline to get some printed copies for Dragon*Con, the last such big event of the year. In the end, I’m very pleased with the result, both artistically and educationally, Kevin looked at proofs and mentioned being gratified at how many bits of science we smuggled in (more or less) painlessly. The combination of line artits Elea Braasch and colorist Chis Spangler worked beautifully, giving a very impressionistic feel to some of the panels. (It was an unexpected bonus that Elea improved dramatically on my actual hair).

The opening event is at 10 p.m. EDT on Friday, September 3. That’s 0200 UT on the 4th – 3 a.m. UK summer time and 4 a.m. across the Channel. Nonetheless, Hanny plans to Skype in so the crowd can “meet” her live. They have booked the Crystal Ballroom at the Hilton for the event. Oddly enough, this is a prime event time for the Con, where things happen 24 hours each day. (In fact, I head afterwards to one of my nightly Live Astronomy events where I’ll be taking requests for objects to take images of with a telescope in Chile). We’ll start with a short talk on the discovery and scientific interest of the Voorwerp, some background on the webcomic, handing out print copies to people there, Hanny’s remarks, door prizes, and a “dress like a Voorwerp” contest. (I have been too busy to find out what kind of material glows bright green under UV light, which would be just the thing.) For those not able to join us in Atlanta, the event will be videocast via UStream. That link also gets you to a form allowing you to order printed copies shipped anywhere at cost, and downloads of promotional posters and cards. Since it’s a webcomic, you can also read it online here once we’ve started the premiere event.

Live or virtual, please join us, and share in the story…

Why build the Hubble Space Telescope?

After I had started my post about the planning phase of the HST up to the start, I have noticed that the arguments (which I thought to be a small section in there) for building a Space Telescope in the first place took up quite some space, so I have decided to post this for now and delay the rest of the post into a different one (trying to keep the posts from getting too extensive as I promised last time), possibly the next.

At first sight it doesn’t sound like a terribly good idea to put an expensive telescope on an expensive rocket (which doesn’t mean it’s a successful start at all, usually expensive equipment and large quantities of explosives are kept well apart for a reason) and shoot it into orbit where again many things can (and did) go wrong and telescope maintenance is either impossible or at least very expensive. Why not simply build a ground-based telescope which is a lot cheaper but would still have a much bigger mirror (so can collect more light and potentially create sharper images, see below) and would still be much cheaper and easier to maintain? Where a new camera simply needs to be screwed on (a simplification about which many telescope engineers could rightfully complain), rather than having to employ the (again expensive) space shuttle to even get there in the first place and then having to work in unhandy space suits to get the new equipment in (with the risk to notice that a bolt might be too long and the camera doesn’t even fit in); and if it doesn’t work afterwards, you’re screwed and you cannot simply take it down again and fix it? Not even talking about potentially simple problems like cooling the camera chips for which you need liquid nitrogen or helium, which, on earth, you can simply refill with a tank, but which in space becomes a rather more complicated task altogether.

So at first sight, it looks like people need a very good reason to even think about Space Telescopes, an then start developing, maintaining and upgrading one with new cameras. So what are these advantages that made scientists built the HST (and many other Space Telescopes)?

Well, there are 2 main reasons, one of which solves a problem that was at least impossible to overcome back then and one that solves a fundamental problem alltogether:

The first problem: In principle, the angular resolution of a telescope should be given by the wavelength of the observed light and the diameter of the mirror (or lens). This is simple optics that every physics student learns and it says that the bigger a mirror, the better the resolution. But there is one very large problem: This is pure theory for an ideal telescope in a vacuum. As in the old physicist joke: ‘Yes, I’ve got a solution, but it only works for spherical elephants in a vacuum’. But here, talking about telescopes instead of elephants, the problem really IS the atmosphere which changes the situation completely.

The first problem: In principle, the angular resolution of a telescope should be given by the wavelength of the observed light and the diameter of the mirror (or lens). This is simple optics that every physics student learns and it says that the bigger a mirror, the better the resolution. But there is one very large problem: This is pure theory for an ideal telescope in a vacuum. As in the old physicist joke: ‘Yes, I’ve got a solution, but it only works for spherical elephants in a vacuum’. But here, talking about telescopes instead of elephants, the problem really IS the atmosphere which changes the situation completely.

The atmosphere has its upsides for breathing, weather (sometimes we could do with a bit less atmosphere here in England 😉 ), airplanes and stuff, but for astronomers, it’s really just ‘in the way’. The air, or better to say the movement of the air, the turbulences of hot and cold air bubbles, bends the starlight on its way into the telescopes (very much like when you’re looking over the tarmac on a very hot summers day everything is flickering). This basically makes stars jump around very fast (Actually, you can see this effect by looking at the stars. Stars ‘flicker’ at night. Objects larger than this effect, e.g. planets, don’t flicker; That’s how you can tell them apart easily). As the apparent position of the stars jump around faster than the eye or a normal camera can detect, it doesn’t really make stars move in long-time exposures, but it leads to ‘blurring’ of the image (If you want to know what a stars picture actually looks like in extremely short exposures, read this article).

This effect is so big that it easily overpowers the resolution improvement due to a bigger mirror size. In fact, to get the maximum resolution of a telescope at sealevel, a telescope with something between 10 and 20 cm diameter is big enough. Any bigger than that does not increase the image resolution due to seeing. Groundbased telescopes can therefore not see details smaller than 0.5-1.0 arcsec in size, even at the best telescope sites (which are usually in very dry places very high up. Dry weather is usually less turbulent and building telescopes at high altitude avoids having to look through large parts of the atmosphere in the first place, so ‘seeing conditions’ are usually better). For comparison, the Hubble Space Telescope has a resolution of only 0.05 arcsec due to it’s position outside the atmosphere and its size of around 2.5 meter.

I show the effect of seeing in the images above. The top one is a picture taken by a 2.2 meter (so similar to HST) telescope in Chile from the Combo-17 survey. The bottom one is the same area of the sky taken by HST (to be precise, it’s a small bit of the Hubble Ultra Deep Field H-UDF, stay tuned for one of my later posts about this survey). You can clearly see that all the objects in the groundbased survey are blurred and some of the faint objects are actually blurred so much, that they cannot even be seen at all above the sky background. In the space based image, the details and features of the galaxies are visible much more clearly. This is the reason why these images were now chosen to be classified in Galaxy Zoo: Hubble. From groundbased telescopes a classification of galaxies at similar distances is simply not possible.

Of course, a big telescope has another obvious advantage: It collects a lot of light, so it enables us to see fainter objects. This is the main reason why telescopes in the past were built bigger and bigger and this trend continues even today.

Also, there are a few things that can be done to improve the image quality, but most of them go beyond the scope of this blog, but if you want to know about it, read e.g. this article and links therein. Basically, either interferometry (where several telescopes far apart are used, unfortunately, this does not produce a full ‘image’ of the object) or movable and distortable mirrors can be used. The latter is called adaptive optics, a very complicated and expensive technique, in which the wavefront of the starlight that has been distorted by the atmosphere can be corrected by a mirror, which is generally speaking distorted exactly in the opposite way to make the wavefront flat again (The mirrors shape has to be adjusted around 200 times per second). A flat wavefront will create a sharp – ‘diffraction limited’ – image, using the complete power of the big mirror used. Adaptive optics was only developed in recent years on several telescopes. The Hooker telescope mentioned in my last blog runs one, for example, and most big telescopes like Gemini, Keck or the VLT run these facilities, too. Although I did call this technique ‘expensive’, it is, of course, a lot cheaper than building a Space Telescope.

In fact this is one of the reasons why the HSTs ‘successor’, the JWST telescope (also one of my later posts) will not be observing at the same optical wavelengths as HST but will rather concentrate on IR wavelengths. Running adaptive optics facilities, groundbased telescopes now produce images of the same quality as the HST, although on a smaller field of view and only close to stars (they need bright-ish stars to compensate the effect of the atmosphere, although laser guide stars will avoid at least the second problem in the future). The 30-40 meter telescopes that are currently planned around the world will show much better resolution again and using very sophisticated adaptive optics might have a similar or even bigger field of view as HST currently has. In the image below (please click for full resolution), you can see an estimated example for a telecope called OWL (Overwhelmingly Large telescope, not kidding, the image above shows a simulation. The speck in the foreground is a car for size comparison). This was a planned telescope which has now been cut down to 42 meters, we now call it the E-ELT (the Extremely Large Telescope, yes, astronomers are not very creative when it comes to telescope names). It’s design is different (but OWL of course is more impressive and their website provided the images I was looking for), but very recently, its cite has been selected to be on a neighbouring mountain to Cerro Paranal, the cite of the VLT.

As you can see on the left, this telescope would, with perfect adaptive optics (diffraction limited) indeed produce much sharper images with much higher resolution then even HST can provide today. So in principle, the problem of the atmosphere can be overcome using clever techniques. The field of view on which this works today is still a lot smaller than what is covered by HST survey cameras, but this is a matter of technique and might be overcome in the future (if interested, google ‘multiconjugate adaptive optics’). In the past, when HST was planned, non of this existed, so a Space Telescope indeed sounded like a good idea.

But groundbased telescopes have an even more fundamental problem which is simply put impossible to overcome. At ground level, only certain wavelengths in the electromagnetic spektrum can be observed. (Far) Infrared, ultraviolet and gamma light cannot be observed at all from groundbased telescopes as the light is strongly absorbed by the atmosphere. The image on the right shows the height above ground at which light is basically absorbed by the atmosphere. As you can see, only optical and radio (and a bit near infrared) observatories make sense on earth, even on the highest mountains. For any other wavelength, you need a space telescope to be able to observe galaxies at all.

But groundbased telescopes have an even more fundamental problem which is simply put impossible to overcome. At ground level, only certain wavelengths in the electromagnetic spektrum can be observed. (Far) Infrared, ultraviolet and gamma light cannot be observed at all from groundbased telescopes as the light is strongly absorbed by the atmosphere. The image on the right shows the height above ground at which light is basically absorbed by the atmosphere. As you can see, only optical and radio (and a bit near infrared) observatories make sense on earth, even on the highest mountains. For any other wavelength, you need a space telescope to be able to observe galaxies at all.

NGC1512 screengrab from Wikipedia

Different wavelengths can be very interesting, a galaxy looks completely different in optical than in X-ray or Radio and all these wavelengths show different physical parameters, e.g. star formation rates (X-ray) or the amount of ‘dust’ in the galaxy (in IR). A good and famous example for this is NGC 1512, a barred spiral galaxy whose center has been observed at different wavelengths by the same telescope. You can see the results on the right. Generally speaking, very blue light (shown in purple) shows very young stars, redder light (up to orange) older stars, red shows dust. Remember, these are all still more or less optical wavelengths, in X-ray or far infrared, this galaxy would look even more different.

The HST works at optical wavelengths, so this was not really a reason to build it, most things (although HST does have some IR filters) could indeed be observed by groundbased telescopes. But as I mentioned above, the HSTs successor, the JWST will exclusively be working in IR for exactly this reason. Optical cameras are not really needed in space anymore (although it’s of course a shame that we won’t have an optical space telescope in the future), but for IR observations it’s vital to be in space. Other famous Space Telescopes in other wavelengths include Spitzer (IR), Chandra (X-ray), GALEX (UV) and XMM-Newton (Xray), all of which are impossible to be replaced by earth-bound instruments.

There are also quite a few focused satellites for certain experiments in space, e.g. WMAP (to observe the afterglow of the Big Bang), Keppler (to detect exo-planets, planets around other stars than the sun) and others, but these are focused projects and not open telescopes everybody can apply to, which of course everyone can at the HST. I will talk about this and some big projects that successfully got their time on the HST in my future posts.

All in all, you can see, there are several good reasons to build a Space Telescope, scientists don’t do this because it’s ‘fun’ or ‘cool’. For observations in certain wavelengths it is still important today, for others it has at least been important in the past. Which brings us back on track: At some point, the decision was made to build the HST (although it wasn’t named Hubble then) and the planning began. But this will be my next post, so stay tuned. I am travelling a lot in the next month, so I might not be able to hold the 2-week schedule, but I’ll do my best.

Cheers,

Boris

Previous history of this series:

- August 2nd, 2010: Me, HST and the History of Surveys

- August 16th, 2010: Edwin Hubble, the Man behind the Telescope

Preethi's Cross-Eyed Galaxy

Remember this object from back in February? It turned up in a paper that I was reading today, going by the name of Preethi’s cross-eyed galaxy.

The paper, by Preethi Nair (now in Italy) and Roberto Abraham from the University of Toronto, is going to be really important as we analyze data from Zoo 2 and from Galaxy Zoo : Hubble. As part of her thesis work, Preethi examined over 14000 galaxies – twice each, to check for consistency (!) – in order to produce the largest detailed morphological catalogue in existence. We’ll be comparing your results to hers, and hopefully showing that the classifications for the other 280,000 or so galaxies in Zoo 2 are as reliable as her 14,000.

Or at least, that’s the theory. In practice I’ve spent the day trying to be sure I understand which of her objects match which of ours. But seeing an old friend – albeit with a new name – crop up still made me smile.

A Comic Voorwerp

This past Monday, at about 8pm Central (GMT -4), a Voorwerpish webcomic was delivered to Sips Comics for printing. Tuesday morning we got the page proofs, and now, one by one, they are being made into full color reality.

We could say a lot of things right now: We could tell you about playing round robin with the script, digitally passing it from person to person under the guidance of Kelly, sometimes into the wee hours of the night. We could tell you about watching the art come to life; transforming from line drawings to fully rendered pages in the hand of our artists Elea and Chris. We could tell you how many pencil tips were broken, and how many digital files grew so big our computers crawled.

We could talk a lot, but instead, let us invite you to join us for the World Premier and share with you a few images.

You’re Invited to a World Premier

- Time: 3 September, 10pm Eastern (GMT -5)

- Online: via Hanny’s Voorwerp Webcomic or via direct UStream Link

- In Person: At Dragon*Con

Crystal Ballroom

Hilton Atlanta

255 Courtland Street NE

Atlanta, GA

Come meet the artists, hear a brief talk by Bill, and generally revel in the Voorwerp’s awesomeness.

And come dressed as a Voorwerp for a chance to win a prize for best costume!

See you in Atlanta?

Pamela, Hanny, Bill, Kelly, Elea and Chris