Eight years, eight Hubble Voorwerpje targets

It’s a week until the 8th anniversary of the launch of Galaxy Zoo.

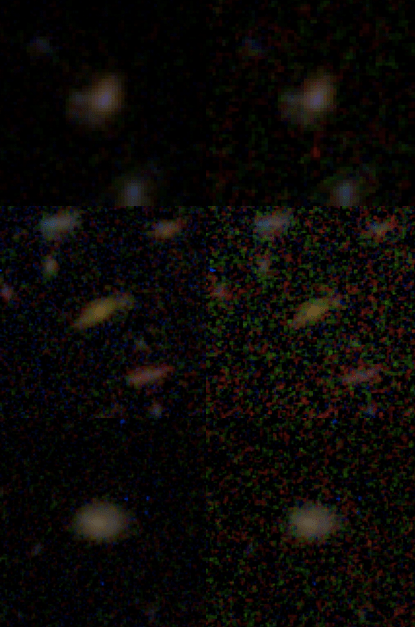

The Hubble Space Telescope observations of giant ionized Voorwerpje clouds near galaxies with active nuclei, many found for the first time though the effort of Galaxy Zoo participants gives us another 8 – one at the end of a long road of numbers. 16,000 galaxies with known or possible active nuclei, 200 highly-ranked cloud candidates based on input from 185 participants, 50 spectroscopic observations, 19 giant ionized clouds, among which we found 8 with evidence that the nucleus has faded dramatically (and then observed by one Hubble Space Telescope). (You wondered where the numeral 8 would come in by now… and there is another one hidden below.) The first batch of scientific results from analysis of these images was described here, and the NASA/ESA press release with beautiful visualizations of the multi-filter image data can be seen here. As a visual summary, here are the images, with starlight and emission from [O III] and H-alpha shown in roughly true visual color.

This project was an outgrowth of the discovery of Hanny’s Voorwerp, which remains probably the signature discovery of Galaxy Zoo. In astronomy, one is a pet rock, ten is a statistically valid sample – so we wanted to know more about how common such clouds might be, and what they could tell us about quasars more generally. Zoo participants answered this challenge magnificently.

The scientific interest in these objects and their history remains intense, and observations continue. I’ve recently finished processing integral-field spectra from the 8-meter Gemini-North telescope, where we have spectra at every point in a small field of view near the nucleus, and just recently we learned that our proposal for spectra in a few key areas at the high resolution of the Hubble telescope has been approved for the coming year.

Even (or especially) for kinds of objects behind its original statistical goals, Galaxy Zoo has provided an amazing ride these last 8 years. Stay with us – and if you see weirdly colored clouds around galaxies, feel free to flag them in Talk!

Now back in Technicolor!

The science team and I want to thank to everyone who’s helped participate in the last month of classifications for the single-band Sloan Digital Sky Survey images in Galaxy Zoo, which were finished last night! The data will help us answer one of our key science questions (how does morphology change as a function of observed wavelength?), helping explore the role played by dust, stellar populations of different ages, and active regions of star formation. Researchers, particularly those at the University of Portsmouth, are eager to start looking at your classifications immediately.

In the meantime, we’re returning to images that are likely more familiar to many volunteers: the SDSS gri color images from Data Release 8. These galaxies still need more data, especially for the disk/featured galaxies and detailed structures. However, we should have two new sets of data ready for classification very soon alongside the SDSS, including a brand-new telescope and something a little different than before.

Please let us know on Talk if you have any questions, particularly if you have feedback about the single-band images or the science we’re working on. Thanks again!!

Stellar Populations of Quiescent Barred Galaxies Paper Accepted!

A new paper using Galaxy Zoo 2 bar classification has recently been accepted!

In this paper (which can be found here: http://arxiv.org/abs/1505.02802), we use hundreds of SDSS spectra to study the types of stars, i.e., stellar populations, that make up barred and unbarred galaxies. The reason for this study is that simulations predict that bars should affect the stellar populations of their host galaxies. And while there have been numerous studies that have addressed this issue, there still is no consensus.

A graphic summary of this study is shown here:

In this study, we stack hundreds of quiescent, i.e., non-star-forming, barred and unbarred galaxies in bins of redshift and stellar mass to produce extremely high-quality spectra. The center-left panel shows our parent sample in grey, and the cyan and green hash marks represent our galaxy selection for our bulge and gradient analysis. The black rectangle represents one of the bins we use. The upper and lower plots show the resultant stacked spectra of the barred and unbarred galaxies, respectively. We show images of barred and unbarred galaxies in the center, selected with the Galaxy Zoo 2 classifications. Finally, the center-right panel shows the ratio of these two stacked spectra at several wavelengths that reflect certain stellar population parameters.

Our main result is shown here:

We plot several stellar population parameters as a function of stellar mass for barred and unbarred galaxies. Specifically, we plot the stellar age, which gives us an idea of the average age of a galaxy’s stars, stellar metallicity ([Fe/H]), which gives us an idea of the relative amount of elements heavier than hydrogen in a galaxy, alpha-abundance ([Mg/Fe]), which gives us an idea of the timescale it took to form a galaxy’s stars, and nitrogen abundance ([N/Fe]), which also gives us an idea of the timescale it took to form a galaxy’s stars.

The main result of our study is that there are no statistically significant differences in the stellar populations of quiescent barred and unbarred galaxies. Our results suggest that bars are not a strong influence on the chemical evolution of quiescent galaxies, which seems to be at odds with the predictions.

Finished with Hubble (for now), with new images going back to our “local” Universe

Thanks for everyone’s help on the recent push with the Hubble CANDELS and GOODS images. I’m happy to say that we’ve just completed the full set, and are working hard on analysis of how the new depths change the morphologies. In the meantime, we’re delighted to announce that we have even more new images on Galaxy Zoo!

The new set of images now active are slightly different for us, and so we wanted to explain here what they are and why we want to collect classifications for them.

In all phases of Galaxy Zoo so far we have shown you galaxy images which are in colour. The details of how these are created varies depending on which survey the images are from. With the SDSS images, we combine information from three of the five observational filters used by Sloan (g, r, i) to produce a single three-colour image for each galaxy. We’ve talked before in more detail about how those colour images are made. All five Sloan filters and their wavelengths and sensitivity are shown below. You can probably see why we’d pick gri for our standard colour images: these are the most sensitive filters, roughly in the “green”, “red” and “infrared” (or just about) parts of the spectrum.

Each of the SDSS filters is designed to observe the galaxy at a different part of the visible (or near visible) spectrum, with the bluest filter (the u-band; just into the UV part of the spectrum) and the reddest the z-band (which is into the infra-red). Different types of stars dominate the light from galaxies in different parts of the spectrum, for example hot massive young stars are very bright in the u-band, while dimmer lower mass stars are redder. Galaxies with older populations of stars will therefore look redder, as the massive blue stars will all have gone supernova already.

We are interested in measuring how a galaxy’s classification differs when it’s observed in each of the filters individually. To investigate this specific question, we have put together a selection of SDSS galaxies and instead of showing you a single three-colour image for each, we are showing you separately the original single filter images. We want you to classify them just as normal, and we will use these classifications to quantify how the classification changes from the blue to the red images.

Astronomers have a good “rule of thumb” for what should happen to galaxy morphology as we move to redder (or bluer) filters, but it’s only ever been measured in very small samples of galaxies. With your help we’ll make a better measurement of this effect, which will be really useful in the interpretation of other trends we observe with galaxy colour.

(Hint: some users might want to use the “Invert” button on the Galaxy Zoo interface a little bit more for these images, as some galaxies are more clearly seen when you toggle it.)

Explore Galaxy Zoo Classifications

Visualizing the decision trees for Galaxy Zoo

Today we’ve added a new tool that visualizes the full decision tree for every Galaxy Zoo project from GZ2 onward (GZ1 only asked users one question, and would make for a boring visualization). Each tree shows all the possible paths Galaxy Zoo users can take when classifying a galaxy. Each “task” is color-coded by the minimum number of branches in the tree a classifier needs to take in order to reach that question. In other words, it indicates how deeply buried in the tree a particular question is, a property that is helpful when scientists are analyzing the classifications.

Galaxy Zoo has used two basic templates for its decision trees. The first template allowed users to classify galaxies into smooth, edge-on disks, or face on disks (with bars and/or spiral arms) and was used for Galaxy Zoo 2, the infrared UKIDSS images, and is currently being used for the SDSS data that is live on the site. The second template was designed for high-redshift galaxies, and allows users to classify galaxies into smooth, clumpy, edge on disks, or face on disks. This template was used for Galaxy Zoo: Hubble (GZ3), FERENGI (artificially redshifted images of galaxies), and is currently being used by the CANDELS and GOODS images in GZ4. Although these final three projects ask the same basic questions, there are some subtle differences between them in the questions we ask about the bulge dominance, “odd” features, mergers, spiral arms, and/or clumps.

If you ever wanted to know all the questions Galaxy Zoo could possibly ask you, head on over to the new visualization and have a look!

New paper: Galaxy Zoo and machine learning

I’m really happy to announce a new paper based on Galaxy Zoo data has just been accepted for publication. This one is different than many of our previous works; it focuses on the science of machine learning, and how we’re improving the ability of computers to identify galaxy morphologies after being trained off the classifications you’ve provided in Galaxy Zoo. This paper was led by Sander Dieleman, a PhD student at Ghent University in Belgium.

This work was begun in early 2014, when we ran an online competition through the Kaggle data platform called “The Galaxy Challenge”. The premise was fairly simple – we used the classifications provided by citizen scientists for the Galaxy Zoo 2 project and challenged computer scientists to write an algorithm to match those classifications as closely as possible. We provided about 75,000 anonymized images + classifications as a training set for participants, and kept the same amount of data secret; solutions submitted by competitors were tested on this set. More than 300 teams participated, and we awarded prizes to the top three scores. You can see more details on the competition site.

Since completing the competition, Sander has been working on writing up his solution as an academic paper, which has just been accepted to Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS). The method he’s developed relies on a technique known as a neural network; these are sets of algorithms (or statistical models) in which the parameters being fit can change as they learn, and can model “non-linear” relationships between the inputs. The name and design of many neural networks are inspired by similarities to the way that neurons function in the brain.

One of the innovative techniques in Sander’s work has been to use a model that makes use of the symmetry in the galaxy images. Consider the pictures of the same galaxy below:

From the classifications in GZ, we’d expect the answers for these two images to be identical; it’s the same galaxy, after all, no matter which way we look at it. For a computer program, however, these images would need to be separately analyzed and classified. Sander’s work exploits this in two ways:

- The size of the training data can be dramatically increased by including multiple, rotated versions of the different images. More training data typically results in a better-performing algorithm.

- Since the morphological classification for the two galaxies should be the same, we can apply the same feature detectors to the rotated images and thus share parameters in the model. This makes the model more general and improves the overall performance.

Once all of the training data is in, Sander’s model takes images and can provide very precise classifications of morphology. I think one of the neatest visualizations is this one: galaxies along the top vs bottom rows are considered “most dis-similar” by the maps in the model. You can see that it’s doing well by, for example, grouping all the loose spiral galaxies together and predicting that these are a distinct class from edge-on spirals.

From Figure 13 in Dieleman et al. (2015). Example sets of images that are maximally distinct in the prediction model. The top row consists of loose winding spirals, while the bottom row are edge-on disks.

For more details on Sander’s work, he has an excellent blog post on his own site that goes into many of the details, a lot of which is accessible even to a non-expert.

While there are a lot of applications for these sorts of algorithms, we’re particularly interested in how this will help us select future datasets for Galaxy Zoo and similar projects. For future surveys like LSST, which will contain many millions of images, we want to efficiently select the images where citizen scientists can contribute the most – either for their unusualness or for the possibility of more serendipitous discoveries. Your data are what make innovations like this possible, and we’re looking forward to seeing how these can be applied to new scientific problems.

New Images on Galaxy Zoo, Part 1

We’re delighted to announce that we have some new images on Galaxy Zoo for you to classify! There are two sets of new images:

1. Galaxies from the CANDELS survey

2. Galaxies from the GOODS survey

The general look of these images should be quite familiar to our regular classifiers, and we’ve already described them in many previous posts (examples: here, here, and here), so they may not need too much explanation. The only difference for these new images are their sensitivities: the GOODS images are made from more HST orbits and are deeper, so you should be able to better see details in a larger number of galaxies compared to HST.

Comparison of the different sets of images from the GOODS survey taken with the Hubble Space Telescope. The left shows shallower images from GZH with only 2 sets of exposures; the right shows the new, deeper images with 5 sets of exposures now being classified.

The new CANDELS images, however, are slightly shallower than before. The main reason that these are being included is to help us get data measuring the effect of brightness and imaging depth for your crowdsourced classifications. While they aren’t always as visually stunning as nearby SDSS or HST images, getting accurate data is really crucial for the science we want to do on high-redshift objects, and so we hope you’ll give the new images your best efforts.

Images from the CANDELS survey with the Hubble Space Telescope. Left: deeper 5-epoch images already classified in GZ. Right: the shallower 2-epoch images now being classified.

Both of these datasets are relatively small compared to the full Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) and Hubble Space Telescope (HST) sets that users have helped us with over the last several years. With about 13,000 total images, we hope that they’ll can be finished by the Galaxy Zoo community within a couple months. We already have more sets of data prepared for as soon as these finish – stay tuned for Part 2 coming up shortly!

As always, thanks to everyone for their help – please ask the scientists or moderators here or on Talk if you have any questions!