More Galaxy Zoo News from China

Posting again for Karen Masters who is still in China:

Galaxy Zoo and Karen’s lecture get covered in the Chinese press.

Galaxy Merger Gallery

I’m Joel Miller, I’m just about to start year 13 at The Marlborough School, Woodstock, and I am here at Oxford University working on mergers from the Galaxy Zoo Hubble data as part of my Nuffield Science Bursary. I have/will be looking at the data and plotting graphs to see how the fraction of galaxies which are mergers changes with other factors therefore determining if there is a correlation between these factors and galaxy mergers. Having looked though many images of merging galaxies I found some really amazing ones.

With some of the images from the SDSS I was able to find high-res HST images of the same galaxy and also find out some more information about them.

Spiral Galaxies NGC 5278 and NGC 5279 (Arp 239) in the Constellation of Ursa Major form an M-51-like interacting pair. This group is sometimes called the “telephone receiver”. The galaxies are not only connected via one spiral arm like M-51, but they also have a dimmer bridge between their disks. Spiral galaxies UGC 8671 and MCG +9-22-94 do not have measured red shifts and therefore there is no data on their distances. They may well be a part of a small cluster of galaxies that includes the “telephone receiver”, but this is not determined at this time.

NGC 5331 is a pair of interacting galaxies beginning to “link arms”. There is a blue trail which appears in the image flowing to the right of the system. NGC 5331 is very bright in the infrared, with about a hundred billion times the luminosity of the Sun. It is located in the constellation Virgo, about 450 million light-years away from Earth.

This pair of Spiral Galaxies in Virgo is known as “The Siamese Twins” or “The Butterfly Galaxies”. Both are classic spiral galaxies with small bright nuclei, several knotty arms, and arm segments. Both also have a hint of an inner ring. The pair is thought to be a member of the Virgo Galaxy Cluster. NGC 4568 is currently the host galaxy of Supernova 2004cc (Type Ic) and was also the host of Supernova 1990B a Type Ic that reached a maximum magnitude of 14.4.

Arp 272 is a collision between two spiral galaxies, NGC 6050 and IC 1179, and is part of the Hercules Galaxy Cluster, located in the constellation of Hercules. The galaxy cluster is part of the Great Wall of clusters and superclusters, the largest known structure in the Universe. The two spiral galaxies are linked by their swirling arms and is located about 450 million light-years away from Earth.

This galaxy pair (Arp 240) is composed of two spiral galaxies of similar mass and size, NGC 5257 and NGC 5258. The galaxies are visibly interacting with each other via a bridge of dim stars connecting the two galaxies. Both galaxies have supermassive black holes in their centres and are actively forming new stars in their discs. Arp 240 is located in the constellation Virgo, approximately 300 million light-years away, and is the 240th galaxy in Arp’s Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies.

With the exception of a few foreground stars from our own Milky Way all the objects in this image are galaxies.

An anniversary Voorwerpje

Following on the heels of the 5th anniversary of Galaxy Zoo itself, this week marks five years since Hanny pointed out the Voorwerp.

To help celebrate the occasion, we have new Hubble data on another of

its smallar relatives. This time the telescope pointed toward

SDSS J151004.01+074037.1 (SDSS 1510 for short). This has a type 2 (narrow-emission-line) AGN at z=0.0458. This was (as far as I can tell) first posted on the forum by Zooite Blackprojects, and also identified in the systematic hunt. Here it is in the SDSS:

Aa usual, these are minimally processed Hubble data, and in particular using filters where we can’t get the color right for both clouds and starlight at the same time without more work. As usual, green comes from [O III] and red from Hα , so green is more highly ionized gas. This one is cool enough already – I think of a Martian flamenco dancer with some cobwebs, but your view may vary:

Looking slightly ahead, next week, Alexei Moiseev, known on the Zoo forum from his wrk on a catalog of polar-ring galaxies based on a clever use of Zoo-1 click data, will be working with us next week, obtaining radial-velocity maps of three of these galaxies using the 6-meter Russian telescope in the Caucasus (the BTA, Bolshoi Teleskop Azimutalnyi or Large Altazimuth Telescope).

And on that note, I turn back to a new book on black-hole astrophysics,

which has me peeking ahead to page 749 for a table of timescales for

accretion phenomena. That, and wish everyone a happy, highly-ionized and just slightly late 5th Voorwerpendag!

Galaxy Zoo on the Naked Astronomy Podcast

![]()

The July 2012 of the Naked Astronomy podcast includes an interview I did with them (at the UK National Astronomy meeting this spring) about Galaxy Zoo and why it’s such a great way of learning about galaxies in the universe.

Machine Learning & Supernovae

This post, from Berkley statistician Joey Richards, is one of three marking the end of this phase of the Galaxy Zoo : Supernova project. You can hear from project lead Mark Sullivan here, and from the Zooniverse’s Chris Lintott here.

Thanks to the efforts of the Galaxy Zoo Supernovae community, researchers in the Palomar Transient Factory collaboration have constructed a machine-learned (ML) classifier that can reliably predict, in near real-time, whether each candidate is a real supernova. ML classification operates by employing previously vetted data to teach computer algorithms a statistical model that can accurately and automatically predict the class for each new candidate (i.e., real transient or not) from observed data on that object. The manual vetting of tens of thousands of supernova candidates by the Galaxy Zoo community has provided PTF an invaluable data set which could be used to accurately train such a ML classifier.

The ML approach is appealing for supernova vetting because it allows us to make probabilistic classification statements, in real-time, about the validity of each new candidate. Further, it allows the simultaneous use of many data sources, including both new and reference PTF imaging data, historical PTF light curves, and information from external, on-line sources such as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and the U.S. Naval Observatory. In total, our automated ML algorithms use 58 metrics about each supernova candidate, all of which are available within seconds after PTF detection of the candidate. These metrics—features in ML parlance—are fed into a sophisticated algorithm, which uses the aggregate of information from more than 25,000 historical supernova candidates which were rated by the Zoo to instantaneously determine whether each newly observed candidate is a supernova.

Our “ML Zoo” has been operating since the beginning of 2012 and has been thoroughly tested against the Human Zoo scores. We found that the ML Zoo scores correlate reasonably well with the average Human Zoo scores for 7000 supernova candidates observed during the first 3 months of 2012 (Figure 1). We also discovered that the ML Zoo is more effective at finding supernovae. In Figure 2 we show a plot of the supernova false positive rate (% of non-supernovae that were classified as supernovae) versus the supernova missed detection rate (% of confirmed supernovae that were classified as a non-supernovae) by both the Human an ML Zoos for 345 spectroscopically confirmed supernovae from 2010. Indeed, the ML Zoo achieves a smaller missed detection rate at each false positive rate.

Joseph Richards works in the Statistics and Astronomy departments at

the University of California, Berkeley as an NSF-sponsored

postdoctoral researcher supported by an interdisciplinary

Cyber-enabled Discovery and Innovation grant. His main area of focus

is astrostatistics and he holds a Ph.D. in Statistics from Carnegie

Mellon University. In his academic research, he has developed

sophisticated statistical and machine learning methodologies to

analyze large collections of astronomical data.

Supernova Project Retires

This post, from project lead Mark Sullivan of Oxford, is one of three marking the end of this phase of the Galaxy Zoo : Supernova project. You can hear from Joey Richards of PTF here, and from the Zooniverse team here.

Since August 2009, Galaxy Zoo Supernovae has been helping astronomers in the Palomar Transient Factory (PTF) find exploding stars, or supernovae, in imaging data taken with a telescope in Southern California. This project has been tremendously successful – Galaxy Zoo Supernovae has uncovered hundreds of supernovae in the PTF data that would otherwise have been missed. These discoveries have directly resulted in scientific publications, with many more in the pipeline, and have been observed on telescopes all over the world, including the 4.2-metre William Herschel Telescope. For example, my colleague Dr. Kate Maguire’s paper includes 8 supernovae found by the Zoo, which were subsequently observed using the Hubble Space Telescope. This allowed her to examine the ultraviolet properties of several thermonuclear ‘type Ia’ supernovae, the same type as those used in the original discovery of dark energy and the accelerating universe. The ultraviolet is a probe of the composition of the exploding star, and allowed her to test whether type Ia supernova properties change with time as the universe ages and becomes enriched with heavy elements.

But – all good things must come to an end. One of the goals of Galaxy Zoo Supernovae was to use the Zoo classifications to improve the algorithms that surveys such as PTF use to find supernovae automatically. And the good news is that, after two years of hard work, we have managed to do just that. The full details are explained in a separate blog posting by Dr. Joey Richards at the University of California at Berkeley.

I’d like to take this opportunity, on behalf of everyone involved with PTF, to thank you all for your time and effort in classifying these supernovae for us. We realise how much effort you’ve put in, and it has been very much appreciated.

For those of you who have become addicted to supernovae, don’t panic – there may be further supernova-related projects in a few months time. In the mean-time, watch this space for more publications based on Galaxy Zoo Supernovae discoveries!

Galaxy Zoo Science Wordl

I’ve given a couple of public talks recently on results on galaxy evolution from Galaxy Zoo (at the Hampshire Astronomical Group, and the Winchester Science Festival) and one of the things I like to point out is the quantity and variety of science results we’re getting out. To illustrate that I made the below wordl of words appearing in the abstracts of all the peer reviewed science papers the Galaxy Zoo science team have put out.

This is based on the 30 papers about astronomical objects submitted up until July 2012. I just missed Brooke’s first financial reform paper submitted by a day or two, and I love that this was out of date just as soon as I made it. 🙂

I realise I should sort out things like per cent – percent, and galaxy, Galaxy, galaxies technically being the same thing. But still I think it’s interesting to look out.

Update: Peas are a Mess!

Hi all,

About two weeks ago, a group of astronomers led by Ricardo Amorin posted a new paper on the peas to astro-ph. They used the giant Gran Telescopio Canarias (GranTeCan or GTC) to take really high-quality spectra of some of the peas. What they find is amazing, but not entirely unexpected. We already knew from Carie Cardamone’s paper that the peas are extremely intense starbursts, that is, they form more stars relative to their mass than any other kind of galaxy in the nearby universe. Now, Amorin et al. show that they are a real mess:

A GTC spectrum of a pea from Amorin et al. (arXiv:1207.0509) zoomed in on the Halpha emission line. The Halpha line comes from gas ionised by the powerful radiation from very young stars. The high-resolution spectrum clearly shows that the single Halpha line is actually due to several different components.

The Halpha emission lines of the peas, once studies at high resolution and signal-to-noise, show that they are actually composed of several different lines. The Halpha line is generated by the powerful ionising radiation from young, massive stars hitting the surrounding gas. The multiple lines mean that the peas have several chunks of gas and stars moving at large velocities relative to each other.

This makes sense from what we know from the few peas that have nice Hubble images.

Hubble image of a pea galaxy (Amorin et al. (arXiv:1207.0509)) showing that it actually consists of multiple components; it’s a real mess!

The multiple Halpha lines are almost certainly from these multiple components and suggest that the gas (and stars) in the peas are effectively a turbulent mess. Some of those clumps whiz past each other at over 500 km/sec. Yes, km/sec. Some of the Halpha lines are also broadened suggesting that really energetic events are occurring inside those star-forming clumps, such as multiple supernova remnants or powerful Wolf-Rayet stars.

You can get the full paper as PDF or other formats here on arxiv.

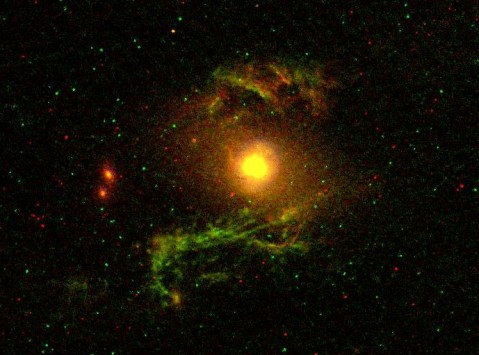

Something rich and strange – Hubble eyes NGC 5972

We just got the processed Hubble images for NGC 5972. This is a galaxy with active nucleus, large double radio source, and the most extensive ionized gas we turned up in the Voorwerpje project. We knew from ground-based data that the gas is so extensive that some would fall outside the Hubble field (especially in the [O III] emission lines – for technical reasons that filter has a smaller field of view). We expected from those data that it would be spectacular. Now we have it, and the Universe once again didn’t disappoint. Another nucleus with a loop of ionized gas pushing outward (this time lined up with the giant radio source), twisted braids of gas like a 30,000-light-year double helix, and dramatically twisted filaments of dust suggesting that the galaxy still hasn’t settled down from a strong disturbance.

Here’s a combination of the Hα image (red) and [O III] (green) data, with the caution that neither has been corrected for the contribution of starlight yet. The image is about 40 arcseconds across, which translates to 75,000 light-years at the distance of NGC 5972. This gives the team plenty to mull over – for now I’ll just leave you all with this view. (Click to enlarge – you really want to.)

![NGC 5972 from HST in [O III] and H-alpha NGC 5972 from HST in [O III] and H-alpha](https://blog.galaxyzoo.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/ngc5972o3ha.jpeg?w=479)