From data to art

When I started writing my post series about the HST (which will be continued soon), I got an email from Zolt Levay from STScI in Baltimore (Space Science Institute, ‘Hubble headquarters’) about how the beautiful HST images are actually made there. We then decided that he would write this up as one of the posts here and we would post it once the GalaxyZoo: Hubble explanations are online on how those special images are made. Now that this has happened, it is time to posts Zolt’s much more general post here.

Enjoy!

Boris

______________________________________________________________

Thanks to Boris for inviting me as a guest blogger here. I have been fortunate to be able to work on the Hubble Space Telescope mission for quite some time. I have spent a lot of that time working with Hubble images. I wanted to use this opportunity to say a few words about how Hubble’s pictures come about. Along the way I hope to give a flavor of the sorts of choices we make to present the pictures in the best possible way, to answer some questions and to correct some possible misconceptions.

The images we see from Hubble and other observatories are a fortunate by-product of data and analysis intended to do science. Hubble’s images are especially high quality because they don’t suffer the distorting effects of the atmosphere since Hubble is orbiting high above the Earth. I won’t go into a lot more detail about Hubble’s technology since Boris has described that nicely in his post “Why build the Hubble Space Telescope?“.

We do aim to produce images that are visually interesting and that reproduce as much as possible of the information in the data. I should also say that these techniques are not unique to Hubble. The cameras used at every large telescope operate pretty much the same way and the same techniques are used to produce color images for the public.

We begin with digital images from Hubble’s cameras, which are built for science analysis. The cameras produce only black and white images because they are designed to make the most precise numerical measurements. They do include a selection of filters which allow astronomers to isolate a specific range of wavelengths from the whole spectrum of light entering the telescope. The black & white (or grayscale) data include no color information other than the range of wavelengths/colors transmitted by the filter. By assigning color and combining images taken through different filters, we can reconstruct a color picture. Every digital camera does this, though it happens automatically in the most cameras’ hardware and software.

We produce color images using a three-color system that reflects the way our eyes perceive color. Most of the colors we can see can be reproduced by a combination of three “additive primary” colors: red, green and blue. Every color technology depends on this technique with some variations: digital cameras, television and computer displays, color film (remember that?), printing on paper, etc.

Here are three images of the group of galaxies known as Stephan’s Quintet from Hubble’s new Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3). The three exposures were made through different filters: I-band, transmitting red and near-infrared light (approximately 814nm in wavelength); V-band (yellow/green, 555nm), and B-band (blue, 435nm). It may not be obvious, but if you examine the image closely you can see there are differences between them. The spiral arms of the galaxies are more pronounced in the B image while the central bulges are smoother and brighter in the I.

We can then assign a color (or hue) to each image. Two things mainly drive which colors we choose: the color of the filter used to take the exposure and the colors available in the three-color model. In this case we assign red to the I-band or reddest image, green to the V-band, and blue to the B-band or bluest image, which are pretty close to the visible colors of the filters. When we combine the separate color images, the full color image is reconstructed.

Because the colors we assigned are not too different from the visible colors of the filters, the resulting image is fairly close to what we might see directly. At least the colors that appear are consistent with the physical processes going on in the galaxies. The spiral arms trace regions of young, hot stars that shine with mostly blue light. The disks and central bulges of the galaxies are mostly made up of older, cooler stars that shine more in red light. Individual brighter stars — foreground stars in our own galaxy — show different colors based on their temperatures: cooler stars are redder, hotter stars are bluer.

We can apply some adjustments to make the picture more snappy and colorful, similar to what any photographer would do to improve the look of their photos. We also touch up some features resulting from the telescope and camera; that explanation may be something that can waits for another post.

Depending on the selection of filters — driven by science goals — and color choices, the images can be shown in various ways. But the motivation behind these and other subjective choices is always to show the maximum information that is inherent in the science data, and to make an attractive image, but also to remain faithful to the underlying observations. We don’t need to heavily process the images; they are spectacular not so much because of how they are processed, but because they are made from the best visible-light astronomy data available.

A variation on this image blending technique needs to be applied with filters that don’t correspond to the standard color model. Narrow-band filters are designed to sample the light emitted by particular elements (hydrogen, oxygen, sulfur, etc.) at specific physical conditions of temperature, density and radiation. These filters are used mostly to observe and study nebulae, clouds of gas and dust that glow because they are illuminated by strong radiation from nearby stars. This very diffuse gas emits light at very, narrow ranges of wavelengths so the color can be very strong or saturated. Some of the most spectacular images result from these clouds that come in all sorts of shapes and textures.

The wrinkle with this sort of observation is that the colors of the filters rarely match the primary colors we would like to use to reconstruct the images. We can choose to reconstruct the color image either by applying the color of the filter, by using the standard primaries or something else entirely. In general a more interesting image results from shifting some of the filter colors. The resulting colors are definitely not what we might see live through a telescope, but they do represent real physical properties of the target.

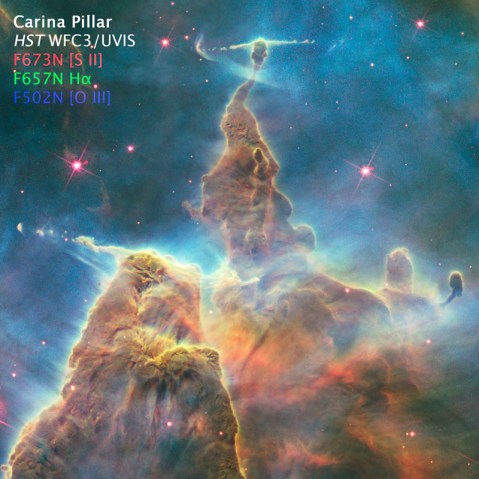

Here are some images of a pillar in the Carina Nebula, taken to celebrate Hubble’s 20th anniversary in 2010. The filters sample light emitted by atoms of hydrogen, sulfur and oxygen. The hydrogen and sulfur both emit red light and the oxygen is cyan (blue-green). The colors and brightness of emission from the various elements depends on the physical conditions in the nebula such as temperature and pressure, as well as the quantity and energy of radiation from surrounding stars causing the clouds shine.

When we apply the colors appropriate to the filters and make a color composite, the separate images look like this:

And the composite color image looks like:

It’s an interesting image, but doesn’t include a wide range of colors because we are starting with only two colors, red and cyan. Let’s try something a little different and shift the colors around a bit:

Here we are using red for the sulfur (the reddest, longest wavelength filter), green for the hydrogen and blue for the oxygen. It may be a little disconcerting; many people know that hydrogen usually shines in red light, but here we are showing it in green. But sulfur also shines in red light here, so the only way to visualize the structures that result from differences between the hydrogen and sulfur is to shift the colors.

If we make the color composite in this way though, see that we now have a fuller range of colors, like an artist’s palette with many more different paint colors. The combinations of colors (like mixed paints) in the composite image result from real differences between the emission coming from the various elements. If they are rendered in the same color those differences are eliminated in the composite. But if we separate their rendered colors, we can show more of the information inherent in the data.

Thanks again for the opportunity to contribute here. I hope this answers some questions about where Hubble’s color images come from. We all hope that Hubble continues beyond its extraordinary 20+ years of amazing science and we can see even more spectacular cosmic landscapes.

More on our fake AGN

Carie’s announcement of the addition of fake AGN has stirred up a storm on the comment thread, and in the forum. I’ve replied where I can, but I think there’s a fundamental misunderstanding that it’s worth highlighting here :

We’re not trying to get you to identify AGN – we want you to classify the galaxies just as you always would. The aim is to test whether the presence of such an AGN affects the classification of the shape of the galaxy. If they do, we need to measure the size of the effect. So don’t go AGN spotting – except for fun – but keep classifying.

I hope that helps.

Chris

P.S. If you do want to know if you’ve identified a fake AGN, then the galaxy’s examine page will say so and the ID will begin AHZ7….

Galaxy Zoo classifications in SDSS Database

The latest release of data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey happened yesterday (SDSS3 blog article about the release). This has been widely talked about as providing the largest ever digital image of the sky, but one thing which might have passed your notice is that as part of this data release your Galaxy Zoo classifications (from the first phase of Galaxy Zoo) have been integrated into the SDSS public database (CasJobs). This will make GZ1 classifications all that more accessible for professional (and amateur?) astronomers to use in their research, and we hope to see some exciting and novel new uses coming out.

I’ll finish by including this visualization of the SDSS3 imaging data made by Mike Blanton and David Hogg (OK so I can’t work out how to embedd a YouTube video here, so here’s the link!).

Fake? AGN Galaxies!

Hidden deep inside the center of most massive galaxies is a central super-massive black hole. However, a in a few percent of galaxies, the black hole is growing in size by accretion of matter. These galaxies are called Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) . By studying these galaxies we can piece together the picture of how galaxies assemble themselves, growing as stars form and their central super-massive black holes accrete matter. In the local universe , we used Galaxy Zoo’s classifications of AGN host galaxies for a study that revealed “The fundamentally different co-evolution of super-massive black holes and their early- and late-type host galaxies”.

But to really understand how most galaxies were built up, we need to look farther back in time, out to where most galaxies in the present day universe were growing most of their mass. Because the light from distant galaxies takes so long to reach us, in Hubble Zoo we are able to see galaxies as they were in the distant past. (In Hubble Zoo most of the galaxies we see are images from ~ 5-7 billion years in the past !). However, as you may have noticed, the Hubble Zoo galaxies appear much smaller. Because the light emitted near an actively growing black hole can be comparable to the light that we see in from an entire galaxy, in Hubble Zoo we have to be careful when classifying galaxies with these luminous centers. To understand what we’re seeing, a team of Galaxy Zoo Scientists have created images, artificially adding the luminous centers of AGN to some of the Hubble Zoo galaxies. These Fake AGN will allow us to determine if how accurately we can classify the host galaxies of the actual AGN in the Hubble Images.

Hanny's Voorwerp and Hubble

And here they are! The Hubble Space Telescope results on Hanny’s Voorwerp (and IC 2497) were just released during the Seattle meeting of the American Astronomical Society. You can see the press release and download several formats of the main image from STScI, download the poster presentation from the meeting, and view the abstract of the meeting presentation, but we can give you the whole story in detail here on the GZ blog. But before that, here’s the money shot:

This combines different filter sets for IC 2497 and Hanny’s Voorwerp, to give the best overall view in a single image. The Voorwerp shows up in [O III] and Hα emission, close to natural color were our eyes sensitive enough. The galaxy IC 2497 is rendered from red and near-IR filters, so it’s a bit redder than we see in other images (for example, from the SDSS or WIYN data). This version does a very attractive job of contrasting the two objects in both color and texture; for reasons you’ll read below, Zolt Levay and Lisa Frattare at STScI had a daunting task to make a single image look this nice from our disparate data sets.

Looking back, we proposed these observations early in 2008, as it was just becoming clear what an interesting object the Voorwerp is and what the right questions might be. It was our good fortune that these observations remained relevant with all we’ve leaned since then, including radio and X-ray measurements. Each data set was specified with a particular goal as to selection of filter or diffraction grating, location, and exposure time. We had images and spectra, the latter looking for material very close to the nucleus of IC 2497 so we could zero in on what’s happening there with much less confusion from its surroundings than we get from the Earth’s surface. Full details of the observation planning appeared in this blog post after our proposal was approved.

The released image product combines four filters and two cameras – the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3), installed during the 2009 shuttle servicing mission, and the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS), electronically repaired during that mission. WFC3 offers superior sensitivity and small enough pixels to exploit the telescope’s phenomenal resolution, while ACS has a set of tunable “ramp” filters that allow us to observe the wavelength of any desired spectral feature at a galaxy’s particular redshift. Our WFC3 images were designed to look at IC 2497, at wavelengths deliberately minimizing the brightness of the gas in the Voorwerp so we could also look for star clusters in its vicinity, that might tell us whether its gas came from a disrupted dwarf galaxy. (This turned out to be a good idea for a slightly different reasons). Our filter choices included one in the near-infrared, at 1.6 micrometers; one in the deep red, close to the SDSS i band, and one in the ultraviolet. Comparing these, we would be able to say something about the age of any star clusters we found. The UV image would also show whether there were any particularly bright clumps of dust, which could serve as “mirrors” so we could later measure the spectrum of the illuminating light source.

The ACS narrow-band filter data were designed to probe the Voorwerp itself, seeking fine structure that is blurred away in ground-based images. We use both the strong [O III] emission (which made it so recognizable when Hanny picked it up from the SDSS images), and the Hα line of hydrogen. Their ratio changes as the conditions ionizing the gas change, so we could watch for variations as conditions differ from place to place. This also netted us gains we hadn’t quite asked for. We also had to work for them. it was known before its repair that the CCD detectors on ACS had suffered from exposure to energetic particles in space during its decade in orbit; all such devices do to some extent. One result of this cumulative damage is that they don’t transfer charge as efficiently as they originally did, and in particular, after being struck by a charged particle (“cosmic ray”), when the image reads out, the detector registers not only a bright spot (which is easy to filter out) but a long trail, so long that it’s not at all easy to filter out without blacking out much of the image. The situation improves if you combine two images, moving the telescope slightly in between them. That lets the software reject the bright cosmic-ray spots, but even after tuning the rejection parameters, the streaks still remain down the device rows. We ended up using what we knew about the remaining trails to filter them out, at the expense of losing the dimmest, smooth regions of emission. Fortunately, these dim regions don’t have enough signal to show new features in Hubble data, so we used ground-based images to fill them in around the edges and in the fainter interior regions of the Voorwerp. This panel shows four successive stages in the process:

Now, as proud as I am of fixing this all up, you don’t really care – you want to know what we’ve actually learned from Hubble. I’m with you – here goes!

Stars are forming in a small part of the Voorwerp. We couldn’t see this from the ground because the regions involved are dim and blend with the overall gas emission. Hubble shows them in two ways. Our filters selected to minimize emission from the gas show bright blue spots, with the size and brightness of young star clusters, in a single area only 2 arcseconds long (about 2 kpc, 6500 light-years). Because the deep-ultraviolet spectrum of starlight is quite different than from an AGN, we see a second signature – the balance between light from [O III] and Hα tips in favor of Hα , again very different from the highly ionized gas elsewhere. In the picture at the top, that makes the star-forming regions show up as the reddish spots near the top bright region of the Voorwerp. These gaseous regions are likewise so small and comparatively dim that we couldn’t see them in even our best ground-based data. The hottest stars are so bright that it’s hard to tell how long these clusters have been forming stars; we know that they include stars so hot that they can be no more than a few million years old. It seems suspicious that we see these star-forming regions only in a small area, which lies closest to IC 2497 at least in our view (we don’t have enough information to be sure it’s really the part closest to the galaxy), and roughly lined up along the direction of outflowing material seen with radio telescopes. This all suggests that the star formation has been set off by compression as gas outflowing from the galaxy encounters the gas in the Voorwerp. We don’t see such star clusters anywhere else in the enormous trail of cold hydrogen of which the Voorwerp is the illuminated part, so their occurrence is connected to the Voorwerp specifically.

This kind of event – an active galactic nucleus blowing gas outward and driving formation of new stars – is one form of feedback, connections between AGN and their surrounding galaxies that seem to be important in regulating aspects of galaxy evolution. We see this process in some other galaxies, in some cases much more intensely than in Hanny’s Voorwerp. A favorite example is Minkowski’s Object, a brilliant emission-line object near the radio galaxy NGC 541 at only a third the distance of IC 2497. In Minkowski’s Object, the central AGN is almost solely a radio object, without the ultraviolet output that ionizes Hanny’s Voorwerp. In that case, where we see ionized gas, it’s lit up by hot, newly-formed stars. This object lies right in the path of the jet of radio-emitting plasma from NGC 541, which is disrupted right as it reaches the object; this looks like a cloud of gas, maybe a dwarf galaxy, that was quietly minding its own business until it was hit by a flow of relativistic particles. Star formation is happening over regions of about the same size in both Minkowski’s Object and Hanny’s Voorwerp, but there are important differences: gas is shedding back away from Minkowski’s Object much more violently than in the Voorwerp, the radio jet in NGC 541 is much more powerful than the small one in IC 2497, and it doesn’t have the additional UV output to light up the gas which is not forming stars. The point I take from this is that the outflowing material reaches the Voorwerp, but with only enough pressure to set off star formation in the densest and closest parts, without the massive reshaping we see in some other galaxies.

The Hole This is probably the most obvious structural feature of the Voorwerp (sometimes seen as the space between the kicking frog’s legs). We wondered whether it might mark the site of some kind of titanic explosion, the space where a jet from IC 2497 drilled its way through the gas, or even the shadow cast by some dense cloud close to the galaxy nucleus. What we learned on this was mostly negative – we do not see streamers of gas blasting away from the hole, or the ionization of the gas being any higher near it, as we would expect for a jet or explosion. The idea of a shadow still makes sense, but we’d still like to know more (maybe from some Gemini-North velocity data still being analyzed).

The nucleus has faded dramatically, but it still knows how to make other kinds of fireworks.One idea we have been investigating, since we saw the first spectra, has been that the nucleus of IC 2497 might have faded in its output of ionizing radiation by hundreds of times since the light that we see reaching the Voorwerp left it. (Ignore for a moment the odd complications of verb tenses involved in light-travel time discussions). What Hubble could add is the ability to measure spectra from very small regions free of the mixing with light from the surroundings that occurs from the ground. This way we could get a good look at the nucleus of IC 2497, how much ionization its gas sees, and whether there might be shreds of highly ionized gas peeking through surrounding obscuring dust and gas which otherwise obscures our view. For this we used two spectra (blue and red) with the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph, newly restored to service by the astronauts of STS-125. We get a clearer measure of the gas – it sees a slightly weaker ionizing source than we thought from the ground because the gas is mostly closer to the core than we would have thought. This fits with the X-ray data in suggesting that the nucleus isn’t just hidden, it really has faded so we see its echo in the Voorwerp. (To indulge once again in a bit of geekdom, “It’s dead, Jim”.)

Or maybe not so much dead as… transformed. The spectra also show something else that we didn’t know to look for. Only a half arcsecond from the core we see a second set of emission lines, redshifted by about 300 km/second from the nucleus. At this location in the ACS images, we see a loop or bubble of Hα emission. The nucleus has been blasting out material, driving this wave into the surrounding gas. Depending on whether it has been slowed down as it snowplows into these surroundings, and on whether it lies exactly in the disk of the galaxy, this would have started less than about 700,000 years ago. This was probably well before the nucleus faded, but connects to an intriguing idea long suggested from looking at the various kids of active galaxies. There may be two modes of accretion power – one in which most of the energy comes out as radiation, and one in which it emerges as kinetic energy of expelled matter (“radio mode”). Has IC 2497 switched between them almost as we watched?

Here is that expanding loop. At left is the Hα image, showing it sticking out above the nucleus. In the middle is a broad-filter image taken to zero in the pointing to take the spectra – you don’t see the loop because it’s swamped by the starlight. At right, the spectrum near Hα showing the distinct emission-line clouds just above the nucleus.

IC 2497 has had a troubled past. It looked a bit odd in our earlier data, but the Hubble images make clear how disturbed this galaxy is. Spiral arms are twisted and warped out of a single plane, and thick dust patches also show that it has yet to settle into a simple form after the disturbance. This looks a lot like the aftermath of a strong interaction – and since we see no other culprit nearby, probably a merger where the other victim is now part of IC 2497. The companion barred spiral just to the east (left) may be only an innocent bystander – it shares the redshift and distance of IC 2497, but is so symmetric and undisturbed that it’s hard to picture it being involved in a collision that wracked the larger galaxy (and tore loose 9 billion solar masses of hydrogen gas from somewhere). These dust patches, plus our better understanding of the Voorwerp’s continuous spectrum aided by the GALEX UV data, now suggest that instead of slightly in front of IC 2497, the Voorwerp is more likely slightly behind it, roughly over the pole of the galaxy. This means that we see the reprocessed radiation via the Voorwerp perhaps 200,000 years after it left the galaxy nucleus. Old news can still be very informative.

Putting it all together, here is the sequence of events that we think led to what we see today. Perhaps a billion years before our present view (which is itself 700 million years behind the times, and there’s nothing we can do about the speed of light), a merger led to IC 2497 forming from two progenitors, with its disk slowly settling but still warped. One product of this merger was an enormous tidal tail of gas, which came to stretch nearly a million light-years around IC 2497. During this process, material accreted into its central supermassive black hole, rapidly enough to produce the energy output of a central quasar as a byproduct, and illuminating and ionizing gas that was exposed to its radiation, to make the Voorwerp. About a million years before we see it, it started to blow material away (and this may have been when its radio jet and outflow started). Then, later still, the core faded, maybe as its energy output switched from being mostly in radiation to mostly powering the motion of material out of the galaxy. And now we see Hanny’s Voorwerp as a very lively echo of the past, as the last radiation from the fading core aces outward but has yet to complete the zigzag trip from galaxy to Voorwerp to us.

Of course, we’d like to test these ideas further. There are plans to improve the spectral mapping, and perhaps look at the history of star formation to tell when things happened to IC 2497. And we want to see whether this behavior is at all common in galactic nuclei – if so, there may have been more active galaxies lately than we thought, and it would change how we think about the relation between “normal” and active galaxies. Zooites have pushed us along greatly in finding smaller cousins – voorwerpjes. But that was a separate meeting presentation…

Live blog : Voorwerp press conference

As anyone who’s been following the twitter feed in the last few days knows, today is a very exciting day for Galaxy Zoo as the long-awaited Hubble Space Telescope image of Hanny’s Voorwerp is released. Kevin has already shown the image in a science talk this morning, and Bill’s poster is up in the conference hall giving more details, but the official release is in just a few minutes. I’m writing live from the press conference room at the American Astronomical Society’s meeting in Seattle, sitting next to the object’s discoverer and namesake Hanny van Arkel and Zooniverse developer Rob who will be keeping twitter up to date.

There’s a separate, long post from Bill ready to go live describing the results, including some very exciting new details, but I’ll use this post to keep you up to date with what happens in the press conference itself.

Three minutes to go…

12.44 : Kevin and Bill are on stage, alongside Leo Blitz of the University of California and Amy Reines from the University of Virginia, who will also be talking about their work during the conference.

12.47 : Press conference starting, but what’s this?

Hubble views Hanny’s Voorwerp

12:52 : Introductions from Rick Feinberg, AAS press officer are over, and Bill’s taking the stand.

12:54 : Bill : ‘Conclusive proof that we have seen a quasar turn off’. Giving the background to the Voorwerp, and introducing Hanny, who immediately became the focus of every camera in the room.

12.56 : The image appears on screen. It looks terrible under the press room lights. Go to the online version, everyone!

12.58 : On to Kevin – the quasar is either hidden or has shut down, in which case the Voorwerp would be an echo of light, not of sound. In the meantime, for those wanting gory details Bill’s blog post is up.

13:00 : IC 2497 does shine in x-rays, but it’s like looking for a floodlight through a bank of fog and finding only a laser pointer – totally inadequate to light up the Voorwerp.

13:04 : In fact, the difference is at least 10,000 times. The timescale on which the reduction must have happened is now believed to be 200,000 years or less (we used to think 70,000 years or less).

13:06 : Back to Bill for one of the major results from Hubble : The bright area close to IC2497 is an area of star formation – so the interaction is triggering star formation in the Voorwerp. We couldn’t have seen this without Hubble, but it fits with the Westerbork radio results that showed evidence for a jet and larger outflow of gas in this direction. We think these are compressing the gas – rather as happens in Minkowski’s object (which was mentioned in my original Voorwerp paper). Much milder in the Voorwerp, though.

13:10 : Spectrum of the main galaxy confirms x-ray results – but we also cut across another area, which seems to be a bubble being blown into the disk of the galaxy – another aspect of an outflow of gas fostered by the nucleus of IC 2497.

13:15 : Bill again : We think that one reason this object is important is because it would be a coincidence for us to get lucky only once, with the nearest quasar. The Galaxy Zoo volunteers have poured through 15,000 candidate images and found 18 related objects – which have been confirmed by follow up. Being presented in another poster, the lead author of which is a Galaxy Zoo volunteer (and undergraduate on a summer program).

13:15 : Dodgy internet connection – sorry! We’re going to try a ustream chat with Kevin, Bill and Hanny after the conference ends. I see Hanny’s mother is watching – we can confirm she’s been very well behaved.

13:22 : Leo Blitz moves us away from the Voorwerp – They believe they’ve found a missing link between galaxies that form stars and those that are dead. A major topic of astronomical interest is how galaxies loose their gas and become old, red and dead. NGC 1266 is an unremarkable galaxy, slightly less massive and smaller than the Milky Way. It has an active galactic nucleus, but to all appearances is otherwise dead. Observations of the molecular gas from which stars mind form show that it’s concentrated in the nucleus of the galaxy. Excitingly, it appears to be fueling a wind that’s been blowing for more than 2.5 million years, and moving fast enough to escape the galaxy. About 13 Sun’s worth of gas escapes each year, and so in about 85 million years’ time, at the current rate, the gas will have been exhausted and the galaxy will have completed its transition to an old galaxy.

13:26 : Our final speaker, Amy Reines, is introducing us to Heinze 2-10. It’s a small galaxy, and yet it hosts a super-massive black hole. In fact, the black hole is the same size as that in the Milky Way but the galaxy is closer to the Milky Way’s satellite galaxies, the Magellenic clouds.

13:30 : Possibly explanation is that black holes form before the bulges at the center of the galaxies do – which would answer an age-old chicken and egg problem! Now on to questions – my laptop is dying, but I’ll hang on as long as I can.

13:36 : Good question on Twitter from Ann Finkbeiner – ‘if the galaxy is 650 million LY away and the quasar turned off 200,000 years ago, how come we’re now seeing it with no quasar?’. We mean that we’re now seeing light that was emitted no more than 200,000 years after the quasar switched off.

Zooniverse's Arfon Smith on NPR SciFri

Listen to Zooniverse technical lead Arfon Smith talk about citizen science on NPR’s Science Friday: http://www.sciencefriday.com/program/archives/201101072

Astrophotography 365 – Completed!

This week’s OOTW features an OOTD by Jules, posted on the 7th of January 2011.

Jules, at the end of 2009, had the idea of an ‘Astrophotography 365’ challenge, where at least one astronomically themed image gets posted on the Galaxy Zoo forum each day in 2010. And it went down extremely well, with just over a thousand images posted!

In the words of Jules:

The level of interest in the thread was unexpected and the contributions came thick and fast. On cloudy nights we had photos of astronomy themed gadgets, toys, books and jewellery! There were several photos posted for each day and the project grew bigger than I had anticipated. I had originally intended to put all the photos into a montage at the end of the year but we had so many contributions that I opted for monthly montages instead in order to make the final one manageable.

The 365 is now complete. We more than met the challenge and here is the result:

| ALICE BLACKPROJECTS BUDGIEYE CATHAL BRISKING GEOFF ECHO-LILY-MAI |

GRAHAMD HANNY HONORARYSPOCK INFINITY JAN JULES KALEBATS |

LAPOMPO LIZARDLY NGC3314 PADDY RENEDEF ROTAR SDREW |

SIRPEPPY STAR MAN STARBRIGHT STARGAZINGMOMMY STELLAR190 SWENGINEER VOLLBARTH |

We had pictures of deep sky treasures such as star clusters, nebulae and galaxies as well as comets stars, planets and the Sun (including its spectrum) and the Moon. Equipment ranged from mobile phones to DSLRs and webcams to remotely controlled scopes like SLOOH and SARA-S. Some contributors had never taken an astrophoto before and produced some amazing results. We also braved all weathers to meet the challenge. I hope we kept people entertained – the thread has had over 42,000 views.

Thanks to everyone who took part. It was huge fun. Maybe we can have a year off and do it all over again! Meanwhile let’s resurrect Alexandre’s old thread and keep clicking in 2011!

She's an Astronomer: Did we really need that series?

A long time ago when I initiated the She’s an Astronomer series I came up with the idea that it would be nice to ask everyone the same questions so that we get a overview of what lots of different (female) astronomers thought about the same issues. I deliberately set up a range of questions to allow the interviewees to focus on both the positive aspects of being involved in astronomy (and particularly the wonderful science Galaxy Zoo does) as well as any negative aspects of being a female in a very male dominated group.

And just in case there are any doubters out there I want to make it very clear that astronomy, both professional and amateur, remains very male dominated at almost all levels (and in professional astronomy, with declining participation the more senior the role). The UK’s professional astronomer group, the RAS has the following statement on the gender make-up of professional astronomers in the UK (admittedly now from 13 year old data):

“The 1998 PPARC/RAS survey for the first time enquired into the gender of members of the UK astronomical community. Women comprised 22% of the population of PhD students, which compares favourably with the 20% of students accepted for undergraduate places in physics and astronomy. However, only 7% of permanent university staff in astronomy are female. Of the UK IAU membership in 1998, 9.2% are female.”

and from our American friends at AAS, they provide a more recently updated table of Statistics which shows the encouraging statistic that in the US now about 40% of the PhD students are now women (but still only about 10% of permanent staff).

Statistics on amateur astronomers are a bit harder to find. You’d think our own Zooite database would help, but unfortunately we don’t track that kind of information. From experience though (as a speaker) I know amateur astronomers are an extremely male dominated group and disappointingly there has been very little change in this over the last few decades. This article in Sky and Telescope (which incidentally pictures one of the professionals we interviewed – Prof. Meg Urry) celebrates the improvement in the numbers of professional women astronomers since the late 70s, but reports that the situation hasn’t changed nearly as much in amateur astronomy: “According to Sky & Telescope reader polls, in 1979 only 6 percent of subscribers were female. By 2002 that number had grown to [only?] 9 percent.” And thanks to my friends on Twitter I found more recent S&T reader demographics which lists only 5% female readers as of January 2010. So that’s very disappointing. And in case you think such figures are somehow S&T only, my friends at the Jodcast tell me their mid 2010 survey of listeners resulted in a figure of 14% women (consistent with 9% women from 2007 within statistical uncertainty).

Anyway back to our She’s an Astronomer series and let’s see what the women who are involved have to say about all this. As it’s been several months now since the last post I’ll remind you that the questions we asked ranged from the personal (to give a bit of background) to more general. They were:

- How did you first hear about Galaxy Zoo?

- What has been your main involvement in the Galaxy Zoo project?

- What do you like most about being involved in Galaxy Zoo?

- What do you think is the most interesting astronomical question Galaxy Zoo will help to solve?

- How/when did you first get interested in Astronomy?

- What (if any) do you think are the main barriers to women’s involvement in Astronomy?

- Do you have any particular role models in Astronomy?

Also if you remember we interviewed 16 different women – which comprised all 8 of the professional astronomers (from students, to senior professor) who had been involved in Galaxy Zoo at that time, plus 8 of the Zooites.

The full list of interviewees was:

- Zooites:

- Hanny Van Arkel (Galaxy Zoo volunteer and finder of Hanny’s Voorwerp). Hanny’s interview in het Nederlands.

- Alice Sheppard (Galaxy Zoo volunteer and forum moderator).

- Gemma Couglin (“fluffyporcupine”, Galaxy Zoo volunteer and forum moderator).

- Aida Berges (Galaxy Zoo volunteer – major irregular galaxy, asteroid and high velocity star finder). Entrevista de Aida en español.

- Julia Wilkinson (“jules”, Galaxy Zoo volunteer. Frequent forum poster.).

- Els Baeton (“ElisabethB”, Galaxy Zoo folunteer. Frequent forum poster, and member of most of the spin-off projects!). Els’s interview in het Nederlands.

- Hannah Hutchins (Galaxy Zoo volunteer, forum poster and co-creator of Galaxy Zoo APOD)

- Elizabeth Siegel (Galaxy Zoo volunteer, forum poster)

- Researchers:

- Dr. Vardha Nicola Bennert (researcher at UCSB involved in Hanny’s Voorwerp followup and the “peas” project). Vardha’s Interview auf Deutsch.

- Carie Cardamone (graduate student at Yale who lead the Peas paper).

- Dr. Kate Land (original Galaxy Zoo team member and first-author of the first Galaxy Zoo scientific publication; now working in the financial world).

- Dr. Karen Masters (researcher at Portsmouth working on red spirals, and editor of this blog series.)

- Dr. Pamela L. Gay (astronomy researcher and communicator based at Southern Illinois University).

- Anna Manning (Masters’ Degree Student in Astronomy at Alabama University working with Dr. Bill Keel on overlapping galaxies)

- Dr. Manda Banerji (recent PhD and author of the machine learning paper)

I’ve been wondering for quite some time if the group agreed with each other on anything, and if we can come up with any interesting conclusions by looking at the different answers to each question. As some of you know I’ve been a bit distracted (little things like having a second baby, and getting some exciting Zoo2 results out), but I have now collated the answers to two of the most general questions (“What do you think is the most interesting astronomical question Galaxy Zoo will help to solve?” and “What (if any) do you think are the main barriers to women’s involvement in Astronomy?”) and plan to present my summary of the responses in upcoming blog posts.

I was going to chicken out and start with the science – the less controversial question (and where there was the most agreement), but thinking about it, perhaps it’s better to get the negative out of the way first, so I’ll leave the exciting science answers for next time and instead start with:

What (if any) do you think are the main barriers to women’s involvement in Astronomy?

Here there was a lot of disagreement, but some interesting trends with the level of formal education/career progression in the field (unfortunately in the sense that there were more perceived problems the longer a person had worked in astronomy).

For the most part the Zooites focussed on the problem of presenting science (to both girls and boys) as a boring/hard subject in schools (and to a lesser extent in the media). Our youngest interviewee, Hannah (who is working on her IGCSEs as a home schooled student) summarized the general view most clearly “because it’s taught so badly at school, it shuts down any interest”, and Alice (a science writer and former science teacher) agrees: “I think poor education is a far worse barrier than gender”. Gemma (a postgraduate student in engineering) muses that perhaps it’s because: “maths and science are [not] presented in an interesting way for girls at school and they are perceived as hard, rigid, dusty disciplines”. And Julia (an amateur astronomer with a degree in Economics) finishes it off by saying that she “think[s] that the media is partly to blame for propagating this myth by getting it badly wrong when presenting some science programmes and portraying maths as something we all hated at school”.

There were some positive views from the Zooites though. Hanny (a Dutch school teacher) expressed a her view that if you’re determined enough you’ll make it: “I can’t think of something that would’ve stopped me to be honest”, and there was a view expressed by the volunteers with more life experience that things were improving with time, for example Julia says: “I think things have improved slightly since [I was at school] but the popular myth still exists that maths is hard and science is stuffy and boring” and Els (a secretary in Belgium) says: “as you can see with the Galaxy Zoo community there are lots of women involved of all ages and backgrounds. So I think we’re getting there, eventually.” Aida (a stay home Mom in Puerto Rico, originally from the Dominican Republic) agrees saying “now I see that the universities [in the Dominican Republic] are full of women studying and that makes me so proud. There are no barriers now for us”.

And our ever resourceful Zooites provided some suggestions for improving the first formal introduction to science. Gemma says it best “if people could see more clearly at a young age how many cool things you can do with maths and science and the sense of achievement you get from problem solving, that they aren’t dry subjects that you learn by rote and that there are still many interesting things to discover, I’m sure a lot more people would be interested, be they women or men.”

From the younger members of the professional astronomers there was really good news in a generally positive feeling that the days of really strong barriers/discrimination are over. Anna (a Masters student) told us that “A female office mate and I were discussing how we don’t think there have been any obstacles for us”, Manda (a recent PhD recipient) says; “I don’t think astronomy is any longer a male dominated subject” and that “today [the many barriers which were around 10-20 years ago are] much less of an issue”, Carie (another recent PhD recipient) says that “I’ve never personally felt any discrimination as a female Astronomer,” and Kate (who recently left professional astronomy after completing her PhD and a first post doctoral position says: “I was always given enormous encouragement from my peers and never felt discriminated against.”. We even hear that (again from Anna) “A male office mate brought up that he believes it is easier to be a woman than a man in astronomy”. Unfortunately the picture coming from the more senior astronomers is not so rosy, and our most senior professional Prof. Meg Urry even explains that this was a shift in opinion for her as she remained in the field: “As an undergraduate and graduate student […] I frankly didn’t expect any problems and I didn’t notice any.”, but “30 years in physics and astronomy have shown me [..] the huge pile of female talent that goes wasted every year.” and that “When I see young women today with those attitudes” (i.e.. that there is no problem), “I find myself hoping that in their case, it will be true” (although she carefully adds that “I don’t think it’s a bad thing to be oblivious, as I was – it probably kept me from dissipating energy fighting the machine”). Unconsciously addressing the view of Anna’s male peer that it might be easier for the women than the men now, she describes that even 30 years ago she was being told that “as a woman, I would benefit (the implication was, unfairly) from affirmative action” and concludes “When people say this today, as they often do, I have to laugh. . I sure do wish it were true [..]”

Many of the professional astronomers focussed on the problems the career path poses. Carie explains the situation: “An astronomer must spend much of her 20s and 30s moving from institution to institution, completing a graduate degree and a couple of postdoctoral positions before finding a permanent position.” and Kate (who gave up on professional astronomy because of her dislike of the career path) says: “I don’t think the academic career path suits women particularly well. […] I personally wasn’t keen on the post-doc circuit of moving about every few years…”, Manda agrees saying: “the need to move around frequently for postdoc positions often means people have to make very tough choices”, and Karen (that’s me – and I’m a fairly senior postdoc now) says: “to remain in a career as a researcher is very difficult for both men and women, and I believe slightly more so for women” and I suggest that this career path “doesn’t seem optimized to retain the best researchers – merely the most persistent or flexible”, but Manda points out that “in my experience there are many men who worry about this too and many women who don’t so I don’t think this is a barrier that is specific to women by any means.”

However, another problem posed by the research career path is the balancing of duel careers, something which preferentially hits women scientists as I explained: “because of the current gender imbalance, a higher proportion of female scientists than male scientists are married to other scientists” and as I know from personal experience “the balancing of two careers as junior academics at the same time is something which is really very difficult and stressful”. Carie agrees: “there are numerous problems to consider if both partners are academics, a common situation for female astronomers”.

Worries about combining a life in research with having a family are also mentioned several times. Carie says that if you’re “thinking about starting a family, it can be very difficult [..]”. and from Vardha (another senior postdoc): “I think that it must be difficult for women to have children while pursuing an astronomical career, since both tasks are quite time demanding.” Alice is the only Zooite to mention the demands of family, but points out that for many women (herself included) “Having a family one day is important enough to me that I would choose that over a career if I was forced to pick one or the other. ” Of course as Vardha says, “there are many women in astronomy who prove that it is possible [to do both]” and in fact we have two examples of professional astronomers with children who were interviewed (that’s me and Meg), although I did say that “having children while a postdoc [was] a difficult choice to have had to make” (and would add that the impact on my staying power in the field is yet to be determined as I do not have that sought after permanent job yet). Alice mentions three more female astronomer role models with children (Cecilia Payne-Gaposkin, Jocelyn Bell-Burnell and Vera Rubin) and says in particular that a blog post on Vera Rubin was “very encouraging on that front” (i.e. the ability to balance astronomical research and having children), but then Manda says that “There are very few female astronomers in very senior academic positions and even fewer who have chosen to have a family”, and goes on to comment that “This does sometimes make me doubt if I can pull off both having a successful academic career as well as a family because there are so few examples of women who have actually achieved this!”

Our most senior professional astronomers (our two Profs: Meg and Pamela) both have comments about the sometimes poor climate and the still prevalent (but usually subtle) discrimination. Pamela says that “I think a lot of academia is still very much an old boys network”, and describes examples of subtle discrimination which just make the women feel they don’t belong (for example “too few women’s bathrooms”, “equipment [..] designed for tall, flat chested, heavy object lifting men” etc.). Meg says that 30 years in the field have shown here that “Fewer women are sought after as speakers, assistant professors, prize winners, than men of comparable ability”. Going back to the school years, Zooite Julia says that “Girls just weren’t encouraged to take sciences”, and Aida recalls how when she was at school (in the Dominican Republic) “girls were supposed to marry young and be housewives”. And not to depress you further, but some of our 16 interviewees had some horrible stories of less subtle discrimination to share. Meg has “seen talented women ignored, overlooked, and sometimes denigrated to the point where they abandon their dreams”, Pamela recalls the common assumption that “since I’m in a physics department, [..] I must be a secretary”. And I remembered that “It was hard to be a teenage girl who was good at maths/science and I spent a lot of time learning to hide it”. From the Zooites, Alice mentioned Cecilia Payne-Gaposkin and Jocelyn Bell-Burnell who she comments were “both treated outrageously unfairly” and has some sad stories of her own to share too.

But moving back to the positive I’ll say again that there was a real sense that things are improving – just very slowly. Pamela (who remember is based in the US which has the worst maternity leave policy of any developed country and poor health care for most people not in stable jobs) concludes her comments with the statement that ” I suspect it will take at least a generation (and major reform to things like maternity leave and health care) for real change to take place, but I believe the change has started.”. I agree saying ” I hope eventually society’s perception of women in science will change […], but I think this will be a very slow process.”

And finally as encouragement for all the girls and women out there interested in astronomy as a career I’m going to reproduce almost the whole last paragraph of Meg’s answer with some helpful suggestions for getting around the problems which remain.

“[..] let me keep it simple: there is discrimination, and it is done by all of us, men and women both, quite unconsciously for the most part. There is a large body of research in the social science literature (which, unfortunately, natural scientists rarely read) documenting the natural tendency of all of us – people raised in a society where men dominate leadership roles in most fields – to undervalue women. I hope young women don’t experience what I did – and there’s a good chance they won’t – but every young woman or under-represented minority scientist should learn about this “unconscious bias” so that, should they ever find themselves getting discouraged or feeling inadequate as scientists, they will correct for the effect of a harmful environment and recognize their own considerable achievements and talents. Or just call me! I’ll be happy to try to reassure them. It’s probably not them, it’s that they are trying to do science in an environment that is unwittingly toxic.”

So that’s why I thought we needed a blog series showcasing the women of Galaxy Zoo. Next time – all the fun science which after all is the reason we all tough it out when we have to!

Preparing the pixels

At Zoo headquarters we like to be efficient. That means avoiding redoing work that has already been done by someone else. Particularly if those others have already spent a long time thinking how to do it best. Getting the images for the original Galaxy Zoo (way back in 2007!) was particularly easy. The fabulous Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) had already done all the work of taking the images, calibrating them, stitching them together, combining images at different wavelengths to make colour images, and optimising their appearance. All we had to do was ask their servers for an image, giving it the required location and size, and voilà, a image ready for adding straight into the Galaxy Zoo collection!

Life was rather more difficult when we added the special ‘Stripe 82’ images from the SDSS. For these, Galaxy Zoo team member Edd needed to do the stitching, combining, optimising, cutting-out and resizing. The details of how he did that are all here. We wanted to be able to compare the Stripe 82 images to the normal SDSS images, so we tried to keep things like the brightness scaling and appearance of colours as similar to the original as possible. Even so, it took us a couple of attempts to come up with a solution we were satisfied with.

With the Hubble data, as with Stripe 82, creating the images for the Zoo isn’t completely straightforward, but again most of the hard work had already been done for us. For the launch of Galaxy Zoo: Hubble, data was taken from several surveys:

- GOODS: The Great Observatories Origins Deep Survey

- GEMS: Galaxy Evolution from Morphology and SEDs

- AEGIS: All-wavelength Extended Groth strip International Survey

We’ve also recently added in COSMOS: Cosmic Evolution Survey images – more about the nitty gritty details of those images in a future post.

The data calibration business was already taken care of by the science teams for each survey. The next steps, finding the galaxies, cutting out images at each available wavelength and combining them into colour images, was handled by Roger Griffith, who already had a system set up to do exactly that. Roger used a nifty piece of software called GALAPAGOS to manage the business of finding, cutting out and measuring the galaxies. The difference that Galaxy Zoo added to Roger’s system was that, like with Stripe 82, we wanted the properties of the colour images to match those from SDSS as closely as feasible, to enable us to compare the results from each of the Galaxy Zoo datasets as fairly as possible.

One particular issue with making colour HST images is that many surveys only produce data at two different wavelengths. Normally, colour images are made by choosing a different wavelength image for each of the three primary colours: red, green and blue. For the HST images we instead use one image for red, another for blue, and then just take the average of the two for green. The primary colours used in your computer display don’t usually match the colour filters that were used in the telescope at all, so the colours you see are only an indication of the true colour. Nevertheless the colours contain a lot of information: galaxies containing only old stars will look red, while those which are actively forming new stars will often be blue. Getting the images looking right, with fairly similar appearance to the SDSS images, required a cycle of testing and exchanging images back and forth, but we came to an agreement fairly quickly.

The HST images in Galaxy Zoo might not look as impressive as some of the press images you’ve seen from Hubble over the past twenty years. That’s because press images are usually picked specifically for their attractive appearance. The images chosen are often of nearby nebulae and galaxies for which HST allows us to see huge amounts of detail. The objects in Galaxy Zoo: Hubble are much more typical of the huge number of galaxies in HST surveys. Although HST can see much more detail than ground-based surveys, its mirror and field-of-view are smaller than most ground-based telescopes, so it can only cover a much smaller area of the sky in a reasonable amount of time. Surveys with the HST therefore focus on faint, distant galaxies, so we end up with images having similar quality to those from SDSS, which is remarkable given how much further away the HST galaxies are compared with those from SDSS.

The similarity between the images of galaxies in the early universe from HST and those relatively nearby from SDSS is actually a big advantage. It means that we can fairly compare the morphologies of galaxies at these two eras in the Universe’s history. That’s what professional astronomers will be doing with your Galaxy Zoo: Hubble classifications over the coming year.