New Sloan Digital Sky Survey Galaxies in Galaxy Zoo

The relaunch of Galaxy Zoo doesn’t only include the fantastic new images from the CANDELS survey on Hubble Space Telescope, but also includes over 200,000 new local galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. We’ve had a lot of questions about where these galaxies came from and why they weren’t put into earlier versions of Galaxy Zoo, so I thought I’d write a bit about these new images.

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey Project (SDSS) is currently in its 3rd phase (SDSS-III). You can read all about the history of SDSS here, and here, but briefly SDSS-I (2000-2005) and SDSS-II (2005-2008) took images of about a quarter of the sky (which we often refer to as the SDSS Legacy Imaging), and then measured redshifts for almost 1 million galaxies (the “Main Galaxy Sample”, which was the basis of the original Galaxy Zoo and Galaxy Zoo 2 samples; plus the “Luminous Red Galaxy” sample) as well as 120,000 much more distant quasars (very distant galaxies visible only as point source thanks to their actively accreting black holes).

Following the success of this project, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey decided they wanted to do more surveys, and put together a proposal which had four components (BOSS, SEGUE2, MARVELS and APOGEE – see here). To meet the science goals of these projects they realised they would need more sky area to be imaged. This proposal was funded as SDSS-III and started in 2008 (planned to run until 2014). The first thing this new phase of SDSS did was to take the new imaging. This was done using exactly the same telescope and camera (and methods) as the original SDSS imaging. They imaged an area of sky called the “Southern Galactic cap”. This is part of the sky which is visible from the Northern Hemisphere, but which is out the Southern side of our Galaxy’s disc. It totals about 40% of the size of the original SDSS area, brining the total imaging area up to about 1/3rd of the whole sky. The images in it were publicly released in January 2011 as part of the SDSS Data Release 8 (DR8 – so we sometimes call it the DR8 imaging area).

This illustration shows the wealth of information on scales both small and large available in the SDSS-III’s new image. The picture in the top left shows the SDSS-III view of a small part of the sky, centered on the galaxy Messier 33 (M33). The middle and right top pictures are further zoom-ins on M33.

The figure at the bottom is a map of the whole sky derived from the SDSS-III image. Visible in the map are the clusters and walls of galaxies that are the largest structures in the entire universe. Figure credit: M. Blanton and the SDSS-III collaboration

We have selected galaxies from this area which meet the criteria for being included in the original Galaxy Zoo 2 sample (for the experts – the brightest quarter of those which met Main Galaxy Sample criteria). Unfortunately in this part of the sky there is not systematic redshift survey of the local galaxies, so we will have to rely on other redshift surveys (the most complete being the 2MASS Redshift Survey) to get redshifts for as many of these galaxies as we can. We still think we’ll get a lot more galaxies and, be able to make large samples of really rare types of objects (like the red spiral or blue ellipticals). Another of our main science justifications for asking you to provide us with these morphologies was the potential for serendipitous discovery. Who knows what you might find in this part of the sky. The Violin Clef Galaxy is in the DR8 imaging area and featured heavily in our science team discussions of if this was a good idea or not.

And interesting things are already being found in just a week of clicks. The new Talk interface is a great additional place for us to discuss the interesting things that can be found in the sky.

For example this great system with tidal tails and a Voorwerpjie:

this weird triangular shaped configuration of satellites:

and an oldie (but a goodie) in the beautiful galaxy pair of NGC 3799 and NGC 3800 (NGC 3799 in the centre, NGC 3800 just off to the upper right):

and just this morning I discovered the discussion of this really unusual looking possible blue elliptical (IC 2540):

There are also rather more artifacts and odd stuff going on in these new images than I think we saw in the SDSS Legacy sample (from GZ1 and GZ2). Remember these are completely new images you are looking at. It really is true that no-one has looked at these in this level of detail (or perhaps ever) before. The original sample had a sanity check at some level, since when GZ1 ran the majority of the sample had already been targeted by SDSS for redshifts (so someone had to plug a fibre into a plate for each galaxy). In this new imaging all that has happened is that a computer algorithm was run to detect likely galaxies and set the scale of the image you see. Sometimes that mistakes stars, satellite trails, or parts of galaxies for galaxies. Always classify the central object in the image, and help us clean up this sample by using the star/artifact button.

And you can enjoy these odd images too. I like this collection of “GZ Pure Art” based on just odd things/artifacts classifier “echo-lily-mai” thought were pretty. 🙂 If you get confused by anything please join us on Talk, or the Forum where someone will help you identify what it is you’re seeing.

A Bit More on the Chinese News about Galaxy Zoo

I’m back in the UK, so I thought it would be nice to give an update on the Chinese coverage of Galaxy Zoo resulting from the big talk I gave in Beijing at the 28th General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union. As you know, I was invited to give one of four “Invited Discourses” at that meeting, on the topic of “A Zoo of Galaxies”. The powerpoint slides of my talk are available online. I still don’t know where/if the video of the talk has appeared online, so will update more on that soon.

As I mentioned before, an abstract of my talk (and a picture of me and one of my favourite galaxies) appeared on the front page of the first edition of “Inquiries of Heaven” (the IAU Daily Newspaper for the meeting).

The talk also attracted a small amount of interest from Chinese press.

Kevin already posted the information that Xinhua (sort of the Chinese version of Reuters) covered it here: Astronomy Project Hunts for Chinese Helpers, (or the Chinese version); since this a news feed it got picked up by a variety of Chinese newspapers.

I was also interviewed for “Amateur Astronomer” (a Chinese astronomy magazine). Here’s the first page of the article they sent me.

Galaxy Zoo on the Naked Astronomy Podcast

![]()

The July 2012 of the Naked Astronomy podcast includes an interview I did with them (at the UK National Astronomy meeting this spring) about Galaxy Zoo and why it’s such a great way of learning about galaxies in the universe.

Galaxy Zoo Science Wordl

I’ve given a couple of public talks recently on results on galaxy evolution from Galaxy Zoo (at the Hampshire Astronomical Group, and the Winchester Science Festival) and one of the things I like to point out is the quantity and variety of science results we’re getting out. To illustrate that I made the below wordl of words appearing in the abstracts of all the peer reviewed science papers the Galaxy Zoo science team have put out.

This is based on the 30 papers about astronomical objects submitted up until July 2012. I just missed Brooke’s first financial reform paper submitted by a day or two, and I love that this was out of date just as soon as I made it. 🙂

I realise I should sort out things like per cent – percent, and galaxy, Galaxy, galaxies technically being the same thing. But still I think it’s interesting to look out.

My Galaxies – Write in Starlight

Long time Zookeeper Steven Bamford has made a new website on which you can easilly write any words you like from the galaxy alphabet.He’s called the website: My Galaxies – Write in Starlight!

Enjoy!

My favourite colour magnitude diagram

I was embarrassed to discover today that I never got around to writing a full blog post explaining our work studying the properties of the red spirals, as I promised way back in October 2009. Chris wrote a lovely post about it “Red Spirals at Night, Astronomers Delight“, and in my defense new science results from Zoo2, and a few other small (tiny people) things distracted me.

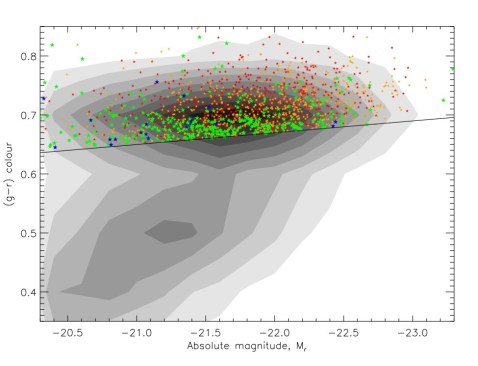

I won’t go back to explaining the whole thing again now, but one thing missing on the blog is the colour magnitude diagram which demonstrates how we shifted through thousands of galaxies (with your help) to find just 294 truly red, disc dominated and face-on spirals.

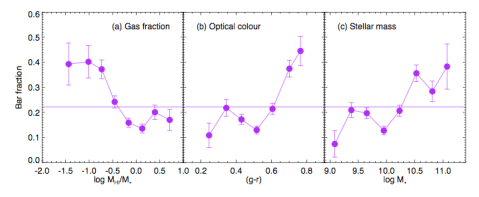

A colour magnitude diagram is one of the favourite plots of extragalactic astronomers these days. That’s because galaxies fall into two distinct regions on it which are linked to their evolution. You can see that in the grey scale contours below which is illustrating the location of all of the galaxies we started with from Galaxy Zoo. The plot shows astronomical colour up the y-axis (in this case (g-r) colour), with what astronomers call red being up and blue dow. Along the x-axis is absolute magnitude – or astronomers version of how luminous (how many stars effectively) the galaxy is. Bigger and brighter is to the right.

So you see the greyscale indicating a “red sequence” at the top, and a “blue cloud” at the bottom. In both cases brighter galaxies are redder.

The standard picture before Galaxy Zoo (ie. with small numbers of galaxies with morphological types) was that red sequence galaxies are ellipticals (or at least early-types) and you find spirals in the blue cloud. The coloured dots on this picture show the face-on spirals in the red sequence (above the line which we decided was a lower limit to be considered definitely on the red sequence). The different colours indicate how but the bulge is in the spiral galaxy – in the end we only included in the study the green and blue points which had small bulges, since we know the bulges of spiral galaxies are red. These 294 galaxies represented just 6% of spiral galaxies of their kind.

So this is one of my favourite versions of the colour magnitude diagram.

Beautiful galaxy Messier 106

Inspired by today’s Astronomy Picture of the Day Image, here’s a quick post about the beautiful nearby spiral galaxy, Messier 106 (or NGC 4258).

|

| M106 Close Up (from APOD) Credit: Composite Image Data – Hubble Legacy Archive; Adrian Zsilavec, Michelle Qualls, Adam Block / NOAO / AURA / NSF Processing – André van der Hoeven |

This is a composite Hubble Space Telescope and ground based (from NOAO) image. The ground based image was used to add colour to the high resolution single filter (ie. black and white) image from HST.

M106 has traditionally been classified as an unbarred Sb galaxies (although some astronomers claim a weak bar). In the 1960s it was discovered that if you look at M106 in radio and X-ray two additional “ghostly arms” appear, almost at right angles to the optical arms. These are explained as gas being shock heated by jets coming out of the central supermassive black hole (see Spitzer press release).

Messier 106 (or NGC 4258) is an extremely important galaxy for astronomers, due to it’s role in tying down the extragalactic distance scale. A search in the NASA Extragalactic Database (NED) will reveal this galaxy has 55 separate estimates of its distance, using many of the classic methods on the Cosmic distance ladder. Most importantly, M106 was the first galaxy to have an geometric distance measure using a new method which tracked the orbits of clumps of gas moving around the supermassive black hole in its centre. This remains one of the most accurate extragalactic distances ever measured with only a 4% error (7.2+/-0.3 Mpc, or 22+/-1 million light years). The error can be so low, because the number of assumptions is small (it’s based on our knowledge of gravity), and as a geometrically estimated distance it leap frogs the lower rungs of the distance ladder.

This result was published in Nature in 1999: A geometric distance to the galaxy NGC4258 from orbital motions in a nuclear gas disk, Hernstein et al. 1999 (link includes an open access copy on the ArXiV).

Because M106 has so many different distances estimated using so many different methods, and is anchored by the extremely accurate geometric distance, it helps us to calibrate the distances to many other galaxies. Almost all cosmological results, and any result looking at the masses, or physical sizes of galaxies need a distance estimate.

So M106 is not only beautiful, it’s important.