An anniversary Voorwerpje

Following on the heels of the 5th anniversary of Galaxy Zoo itself, this week marks five years since Hanny pointed out the Voorwerp.

To help celebrate the occasion, we have new Hubble data on another of

its smallar relatives. This time the telescope pointed toward

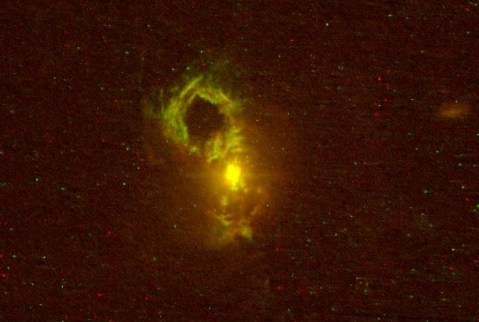

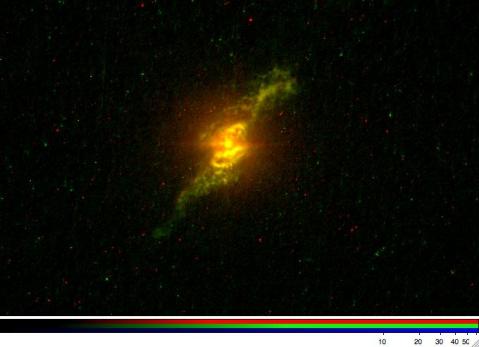

SDSS J151004.01+074037.1 (SDSS 1510 for short). This has a type 2 (narrow-emission-line) AGN at z=0.0458. This was (as far as I can tell) first posted on the forum by Zooite Blackprojects, and also identified in the systematic hunt. Here it is in the SDSS:

Aa usual, these are minimally processed Hubble data, and in particular using filters where we can’t get the color right for both clouds and starlight at the same time without more work. As usual, green comes from [O III] and red from Hα , so green is more highly ionized gas. This one is cool enough already – I think of a Martian flamenco dancer with some cobwebs, but your view may vary:

Looking slightly ahead, next week, Alexei Moiseev, known on the Zoo forum from his wrk on a catalog of polar-ring galaxies based on a clever use of Zoo-1 click data, will be working with us next week, obtaining radial-velocity maps of three of these galaxies using the 6-meter Russian telescope in the Caucasus (the BTA, Bolshoi Teleskop Azimutalnyi or Large Altazimuth Telescope).

And on that note, I turn back to a new book on black-hole astrophysics,

which has me peeking ahead to page 749 for a table of timescales for

accretion phenomena. That, and wish everyone a happy, highly-ionized and just slightly late 5th Voorwerpendag!

Galaxy Zoo on the Naked Astronomy Podcast

![]()

The July 2012 of the Naked Astronomy podcast includes an interview I did with them (at the UK National Astronomy meeting this spring) about Galaxy Zoo and why it’s such a great way of learning about galaxies in the universe.

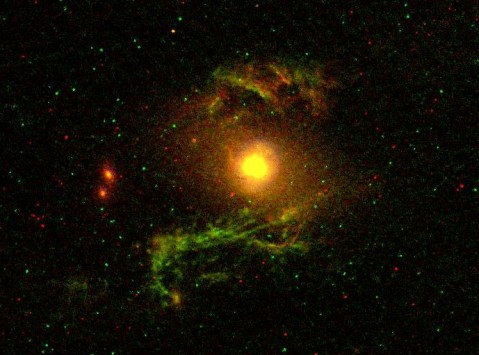

Something rich and strange – Hubble eyes NGC 5972

We just got the processed Hubble images for NGC 5972. This is a galaxy with active nucleus, large double radio source, and the most extensive ionized gas we turned up in the Voorwerpje project. We knew from ground-based data that the gas is so extensive that some would fall outside the Hubble field (especially in the [O III] emission lines – for technical reasons that filter has a smaller field of view). We expected from those data that it would be spectacular. Now we have it, and the Universe once again didn’t disappoint. Another nucleus with a loop of ionized gas pushing outward (this time lined up with the giant radio source), twisted braids of gas like a 30,000-light-year double helix, and dramatically twisted filaments of dust suggesting that the galaxy still hasn’t settled down from a strong disturbance.

Here’s a combination of the Hα image (red) and [O III] (green) data, with the caution that neither has been corrected for the contribution of starlight yet. The image is about 40 arcseconds across, which translates to 75,000 light-years at the distance of NGC 5972. This gives the team plenty to mull over – for now I’ll just leave you all with this view. (Click to enlarge – you really want to.)

Hubble spies the Teacup, and I spy Hubble

Our Hubble image of Voorwerpje galaxies continue to come in, and it seems each one is stranger than the last. Overnight we got our data on the Teacup system (SDSS J143029.88+133912.0). This one attracted attention through a giant emission-line loop over 16,000 light-years in diameter to one side of the nucleus.

I was worried to get email this morning that there had been a failure to lock on to one of the two needed guide stars so that the telescope might have rolled enough during the observations to compromise data quality. Inspecting the data, it looks like we’re OK. We’re OK and the galaxy is strange. This is a composite of [O III] (green) and Hα (red), right out of the software pipeline without any additional processing:

Another giant hole whose origin is obscure. The loop doesn’t even show much sign of being connected to the galaxy. The strongest [O III] does seem to trace out ionization cones, as in showing from structures near the nucleus, but that seems independent of the distribution of the gas. There are filaments in the gas that are nearly parallel, sort of like waves. Well have our work cut out for us to understand more of what’s going on here. I can hardly wait for the next one!

There was an extra treat for me with these observations. Last night, I interrupted a session with my summer class at the campus observatory to look south with binoculars and catch Hubble passing far to the southeast, no more than 13 degrees from our horizon. This was during the Hα exposure, so I saw it while it was doing these observations (it was pointed just about up in my frame of reference, as it happens). I got a picture through a 125mm telescope, showing the telescope streaking by just north of the star k Lupi. At the time, Hubble was 1600 km away over Cuba. Hubble was watching the Teacup, I was watching Hubble, and a couple of slightly puzzled students were watching me.

Chandra X-ray Observations of Mergers found in the Zoo Published

I hope you all had clear skies during the Transit of Venus. If not, it’ll be over a hundred years before you get another chance…. and in Zoo-related news, the Transit of Venus is an example of one way we find planets around other stars. We look for a dip in the brightness of the star as a planet moves across it from our point of view. Want to know more? Head over to the Planethunters blog, or put in some clicks looking for transits yourself!

So, in actual Galaxy Zoo news, I am very happy to report that the latest Galaxy Zoo study has been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal. As we blogged a while back, we got Chandra X-ray time to observe a small sample of major mergers found by the Galaxy Zoo to look for double black holes. The idea is to look for the two black holes presumably brought into the merger by the two galaxies and see if we find both of them feeding by looking for them with an X-ray telescope (i.e. Chandra).

The lead author of the paper is Stacy Teng, a NASA postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and an expert on X-ray data analysis. In a sample of 12 merging galaxies, we find just one double active nucleus.

Image of the one merger with two feeding black holes. The white contours are the optical (SDSS) image while the pixels are X-rays. The red pixels are soft (low energy) X-ray photons, while the blue are hard (high energy) photons. You can see that both nuclei of the merger are visible in X-rays emitted by feeding supermassive black holes.

We submitted the resulting paper to the Astrophysical Journal where it underwent peer review. The reviewer suggested some changes and clarifications and so the paper was accepted for publication.

You can find the full paper in a variety of formats, including PDF, on the arxiv.

So what’s next? We submitted a proposal, led by Stacy, for the current Chandra cycle. To do a bigger, more comprehensive search for double black holes in mergers to put some real constraints on their abundance and properties. We hope to hear about whether the proposal is approved some time later this summer, so stay tuned and follow us on Twitter for breaking news!

Curiouser and curiouser – Hubble and Mkn 1498

Fresh off the telescope, here’s a first view of the “Voorwerpje” gas clouds around the Seyfert galaxy Markarian 1498. Its nucleus, shown in our Lick and Kitt Peak spectra, is a type 1 Seyfert, meaning that we see the broad-line region of gas very close to the central black hole, moving at high velocity. Those data showed highly-ionized gas to a radius of at least 20 kiloparsecs (65,000 light-years). Its nucleus is too dim to account for the ionization of the extended gas clouds, which landed it a spot in our list of seven objects for the Hubble proposal. Getting these data now was an unexpected treat – they were originally scheduled to be taken next November. As another bonus, the good people at the Space Telescope Science Institute just last week implemented the software to deal with charge-transfer problems in the Advanced Camera CCDs, right in the pipeline, improving the image quality a lot (it took months to get to this point with the Hanny’s Voorwerp data). And here it is, Markarian 1498 in a combination of [O III] emission (green) and Hα (red):

This is… interesting. From the few of these galaxies where we have data so far, loops of ionized gas near the nucleus may be a recurring theme. I could add speculations on what we’re seeing in Mkn 1498 – but for now, I’ll just let everyone enjoy the spectacle.

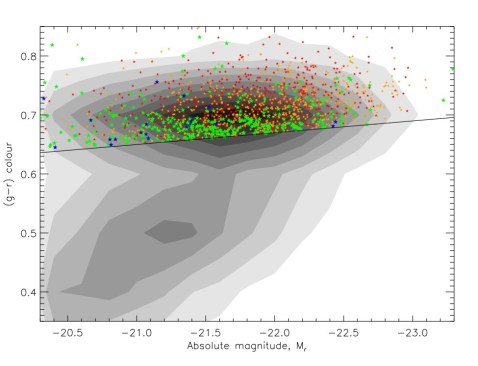

My favourite colour magnitude diagram

I was embarrassed to discover today that I never got around to writing a full blog post explaining our work studying the properties of the red spirals, as I promised way back in October 2009. Chris wrote a lovely post about it “Red Spirals at Night, Astronomers Delight“, and in my defense new science results from Zoo2, and a few other small (tiny people) things distracted me.

I won’t go back to explaining the whole thing again now, but one thing missing on the blog is the colour magnitude diagram which demonstrates how we shifted through thousands of galaxies (with your help) to find just 294 truly red, disc dominated and face-on spirals.

A colour magnitude diagram is one of the favourite plots of extragalactic astronomers these days. That’s because galaxies fall into two distinct regions on it which are linked to their evolution. You can see that in the grey scale contours below which is illustrating the location of all of the galaxies we started with from Galaxy Zoo. The plot shows astronomical colour up the y-axis (in this case (g-r) colour), with what astronomers call red being up and blue dow. Along the x-axis is absolute magnitude – or astronomers version of how luminous (how many stars effectively) the galaxy is. Bigger and brighter is to the right.

So you see the greyscale indicating a “red sequence” at the top, and a “blue cloud” at the bottom. In both cases brighter galaxies are redder.

The standard picture before Galaxy Zoo (ie. with small numbers of galaxies with morphological types) was that red sequence galaxies are ellipticals (or at least early-types) and you find spirals in the blue cloud. The coloured dots on this picture show the face-on spirals in the red sequence (above the line which we decided was a lower limit to be considered definitely on the red sequence). The different colours indicate how but the bulge is in the spiral galaxy – in the end we only included in the study the green and blue points which had small bulges, since we know the bulges of spiral galaxies are red. These 294 galaxies represented just 6% of spiral galaxies of their kind.

So this is one of my favourite versions of the colour magnitude diagram.

Lens Zoo is Coming!

We’re very pleased to tell you that we’ve been awarded developer time from the Citizen Science Alliance to build a new, exciting Zooniverse project to discover gravitational lenses.

What’s a gravitational lens, you might ask? When a massive galaxy or cluster of galaxies lies right in front of a more distant galaxy, the light from the background source gets deflected and focused towards us. These space-bending massive galaxies allow us to peer into the distant Universe at around 10x magnification, and to make accurate measurements of the total (dark and luminous) mass of galaxies.

As many of you know, there has been a long-running and enthusiastic search for lenses in the “weird and wonderful” part of the forum; although lens-finding was never a goal of the Galaxy Zoo project, this forum has turned up some interesting systems which we are still following up. Up until now, the GZ lens search has been quite informal: it has not been easy keeping track of all the candidates that have been suggested! Nevertheless, the Lens Hunters have done an amazing job, collecting and filtering the suggestions as they come in, and teaching themselves and each other about the astrophysics of lensing.

Impressive stuff: enough to persuade a group of professional astronomers that a specially-designed Zoo for identifying lenses could be a powerful way of analyzing the new wide-field imaging surveys that are coming online. In this Lens Zoo we will be able to provide you with new tools – designed, we hope, with you – to find new lenses more effectively. We have teamed up with astronomers from several big surveys who are eager to harness your citizen science power, and will be providing a lot of new, high quality data to be inspected. Over the next 6-10 months we’ll be working hard with the Zooniverse developers to build the Lens Zoo, and we hope you will join us for the ride: Lens Zoo needs you!

Phil, Aprajita, Anupreeta & the Lens Zoo team.

![NGC 5972 from HST in [O III] and H-alpha NGC 5972 from HST in [O III] and H-alpha](https://blog.galaxyzoo.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/ngc5972o3ha.jpeg?w=479)